In its most recent and troubling quarter, Apple indicated that despite losing ground in iPhone sales, including a significant sales slump in China, it believes its next big opportunity should kick in soon. And that big opportunity is India. But will India present the same opportunity Apple thinks it will?

Country Comparisons

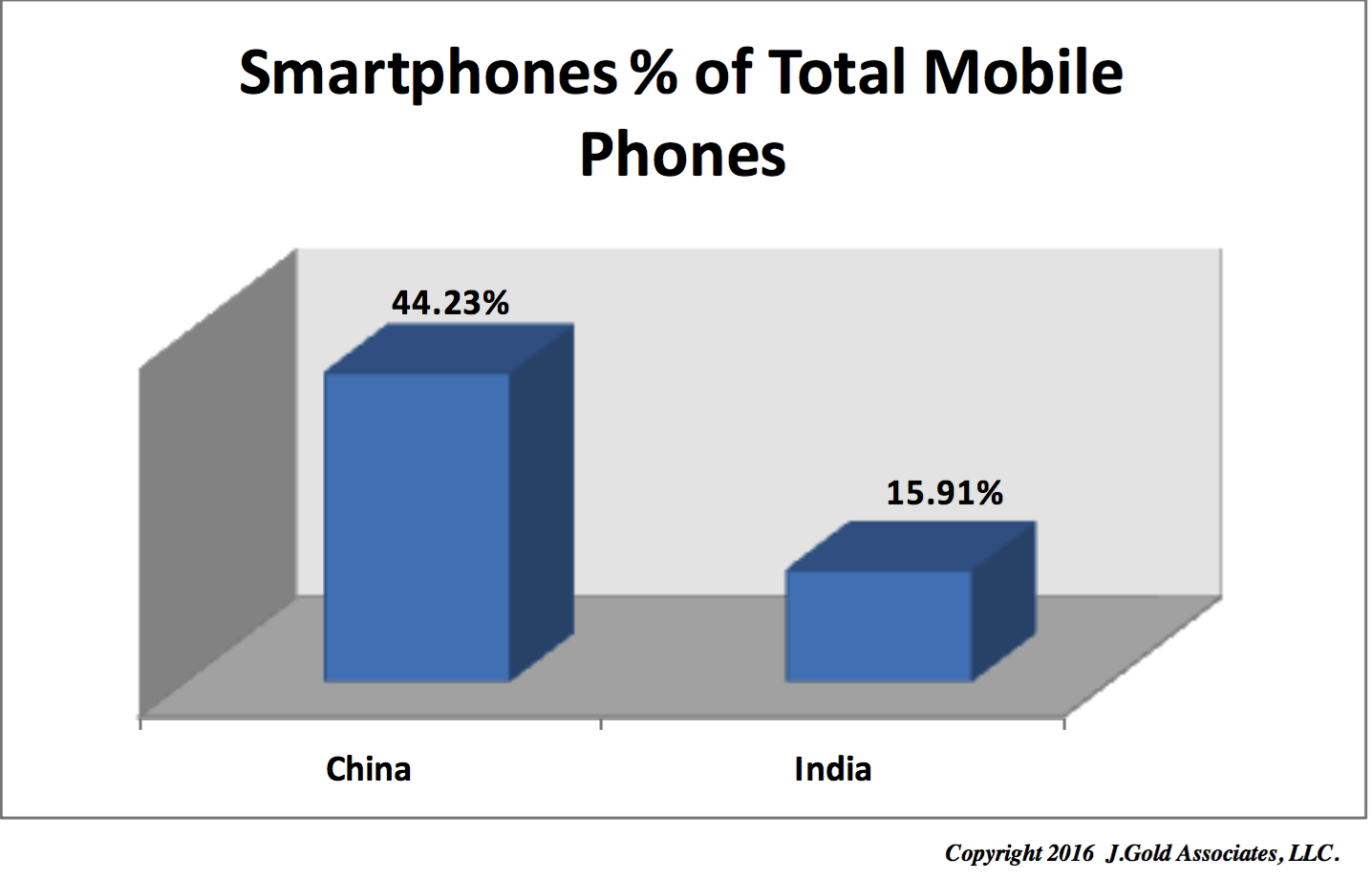

India has a population almost the size of China (approximately 1.4B in China vs. 1.3B in India). China has done well for Apple over the past 2-3 years, bolstering sales in an otherwise saturated market in the mature economies. And India is relatively underrepresented in Smartphone penetration. Indeed, as a percentage of total devices, China currently has about 3 times as many smartphones in use as India does.

But although India is often seen as a “green field” opportunity in general, does it really represent the needed boost over the next couple of years that Apple thinks it will, especially given world macroeconomics that are signaling increased difficulty in emerging markets? Can India make up the slack?

Are There Indicators That Can Help?

In attempting to answer this question, we looked at several possible indicators. Although none are flawless, we decided to concentrate on two primary measurements: the comparable amount of household income in India as compared to China, and the amount of 4G cellular coverage available.

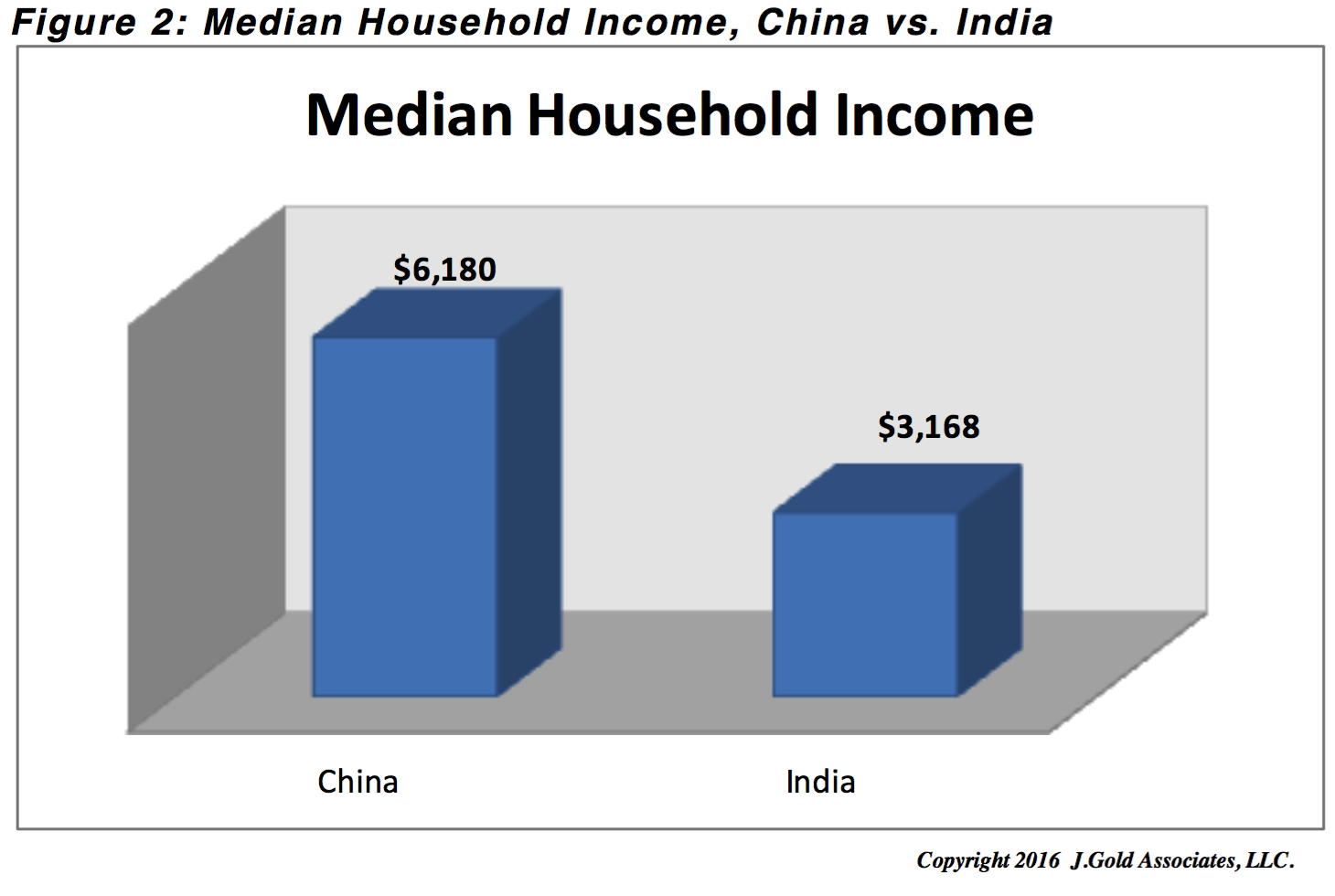

The first as an indicator of device consumption is fairly obvious. The more household income available, the more likely it is that households will spend on the higher end devices that Apple produces (as opposed to low end smart or feature phones that in some cases retail from less than $50). And to purchase Apple services that adds significantly to its bottom line.

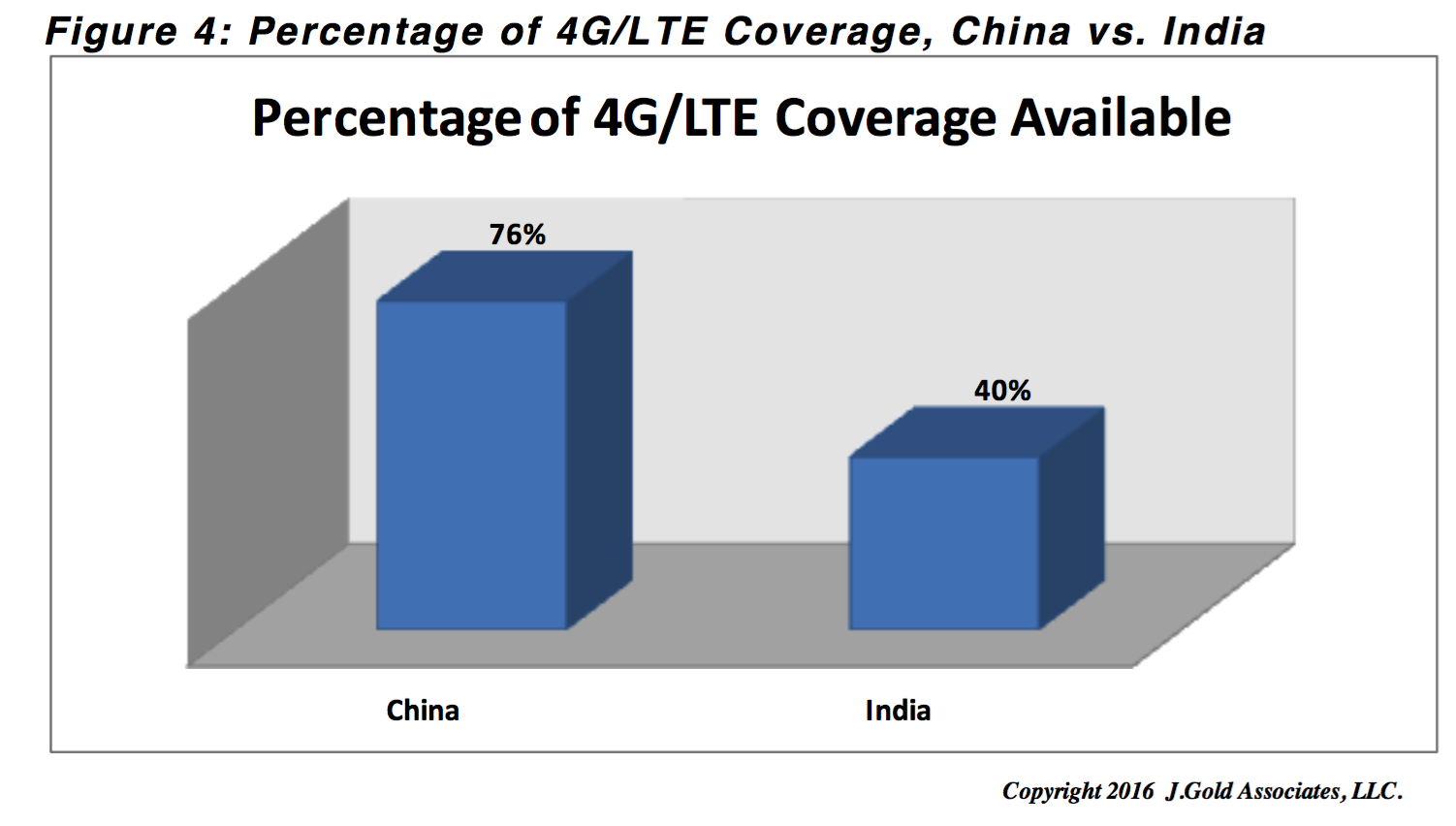

The second indicator, 4G coverage, we considered a valid indicator because it’s unattractive to own a higher end smartphone if you can’t get fast networks to put it to good use. And the majority of advanced features, and especially the services that Apple sells along with the phone, just don’t cut it with inferior networks.

In the case of total household income, there is a large disparity between China and India. Although both countries have many well to do areas primarily in the cities, they also have a large population of rural poor. But China has made many more advances in upgrading its economy over the past decade than India has. As a result, China has nearly twice the median household income of India.

Do Household Incomes Make a Difference?

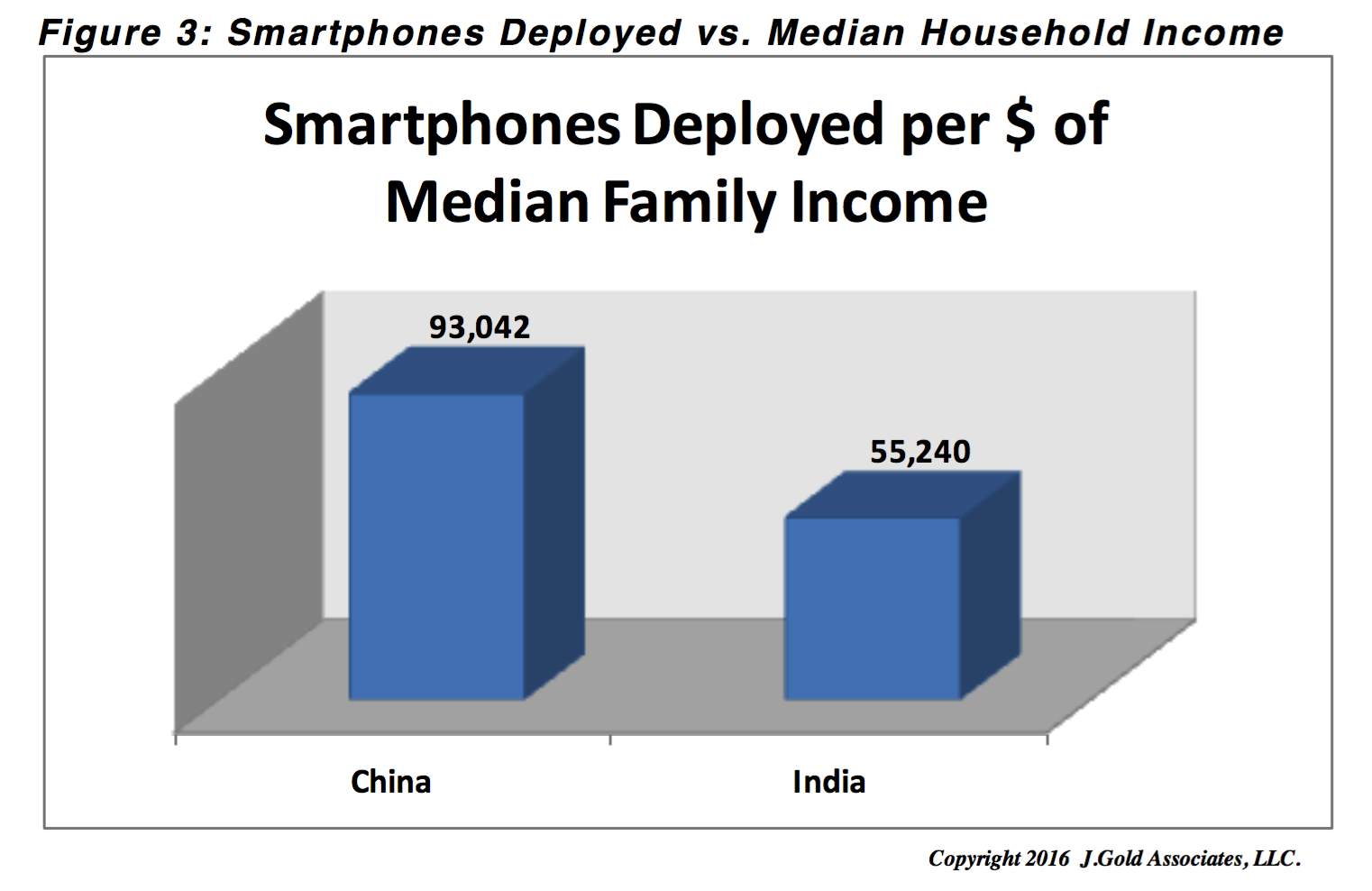

To compare the effect of household incomes, we calculated the number of devices deployed per median household income for both China and India. While not a perfect measure, it is a way to do an equalization of the potential across the two countries by equalizing the economics. We found that China has nearly two times the number of smartphones deployed per dollar of median family income as does India.

Or interpretation of the above indicates that Chinese families are willing to spend more of their discretionary income on smartphones than Indian families do, including potentially purchasing more than one device per household. Why is that? Partially it’s a values issue (smartphones seem to be more of a status symbol in China). But it may also be due to an infrastructure issue, which is the next indicator we’ll analyze.

How Does Cellular Infrastructure Effect Smartphone

Deployments?

There is a disparity between higher capability 4G/LTE networks in China vs. India. To assess if this has an impact, we looked at the availability of fast cellular networks that power the smartphones that people are purchasing.

While various estimates of China’s availability of 4G are fairly consistent, getting good estimates for India proved more difficult and varied widely. We used a figure we believe to be realistic. The comparison shows that China has nearly twice the 4G coverage of India.

For a more balanced comparison, we created an equalization factor for the difference in available coverage. We calculated the number of smartphones being deployed as a percentage of available 4G/LTE coverage. This is an attempt to equalize for the number of devices connected to faster networks, which would favor higher end devices. What we found was that China had nearly twice as many smartphones connected vs. India per percent of high speed network deployed.

Drawing Some Conclusions

So what does all this mean? Based on the above data, we expect that Apple (and higher end smartphones in general) will sell at significantly reduced numbers in India than they do in China. Despite India having fewer smartphones in use and therefore having more upside, it also has a lower level of network capability necessary for best use of higher end smartphones. And it has lower median household income making it more difficult for families to purchase a higher end device, or to buy multiple devices.

In most parts of the emerging world, Android has captured about 85%-90% of the smartphone market. That limits potential Indian sales for Apple even further even though its holds the vast majority of the remaining market share. A comparison of the factors we calculated above shows that the Indian market has significantly less sales volume potential than China in the short to medium term.