There will be more stories about the final agonies of BlackBerry, but this is it. The company announced today that it expects to report a loss of nearly $1 billion in its second fiscal quarter and that it is dumping nearly half of its remaining employees. This is the corporate equivalent of entering hospice care; all that is left is making the end as painless as possible.

There will be more stories about the final agonies of BlackBerry, but this is it. The company announced today that it expects to report a loss of nearly $1 billion in its second fiscal quarter and that it is dumping nearly half of its remaining employees. This is the corporate equivalent of entering hospice care; all that is left is making the end as painless as possible.

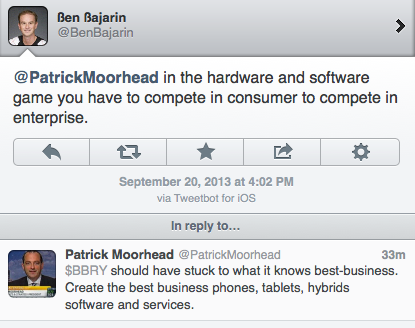

My colleagues Ben Bajarin and Patrick Moorhead got into a discussion on Twitter of just what sealed BlackBerry’s fate. Patrick argued that BlackBerry should have stuck to serving the corporate market it knew, which Ben maintains that these days, you can’t be a corporate player in mobile without appealing to consumers.

They are both right, but the story is a bit more complicated. The fact is that BlackBerry couldn’t give its customers, corporate or consumer, what they wanted because it didn’t know. Co-CEO Mike Lazaridis is a brilliant engineer who I hope will be remembered for his enormous contributions to mobility, but he became convinced he knew what the market wanted even as it was slipping away from him.

Lazaridis was justifiably proud of three BlackBerry hallmark features, each of which he had personally played a personal role in: The excellent physical keyboard, outstanding battery life, and exceptional phone quality. The iPhone, he believed, fell woefully short in all three and he was convinced that loyal BlackBerry customers would never forsake their solid handsets for the iPhone’s easy charms.

He might have been right about the loyalty of corporate customers, who loved the security and manageability that BlackBerry offered for mobiliZing their Microsoft Exchange mail systems. But to keep them loyal, it had to deliver phones that corporate IT managers could get executives–their bosses–to carry in the age of the iPhone.

BlackBerry’s failure to do so wasn’t just stubbornness. By the mid-aughts, the Java-based BlackBerry operating system had reached the end of the line. It was not conducive to a good browsing experience or robust app development. But the company’s strongest asset in the corporate market, the BlackBerry Enterprise Server, was hopelessly integrated with the device OS. It was also architected in such a way that it was all but impossible to support multiple devices on a single account, a necessity once tablets came along.

Way too late, BlackBerry began serious development of a replacement OS based on QNX, a real-time OS it acquired in 2010. But the first QNX-based product, the PlayBook tablet, lacked a BackBerry mail client because engineers couldn’t figure out how to make it run on the new OS. Ultimately, BlackBerry abandoned BES for the QNX-based BlackBerry OS 10 in favor of Microsoft Exchange ActiveSync. Since solid ActiveSync implementations were also available on iPhones and some Android phones, BlackBerry lost much of its corporate cachet.

It’s a sad, sad story, but it is at its end. At this point, the loss of talent has been so severe that it seems unlikely that BlackBerry could execute a recovery plan even if it found a path to redemption.

The world is a stage, but the play is badly cast. ~ Oscar Wilde