A Pyrrhic victory (/ˈpɪrɪk/) is a victory with such a devastating cost that it carries the implication that another such victory will ultimately lead to defeat. The phrase “Pyrrhic Victory” is named after King Pyrrhus of Epirus, whose army suffered irreplaceable casualties in defeating the Romans at Heraclea in 280 BC and Asculum in 279 BC during the Pyrrhic War. Someone who wins a Pyrrhic victory has been victorious in some way; however, the heavy toll negates any sense of achievement or profit. The term “Pyrrhic victory” is used as an analogy in fields such as business, politics, and sports to describe struggles that end up ruining the victor. ~ via Wikipedia

Series Schedule:

- Mon: The Battle for the PC

- Tue: The Battle for Mobile Phones Won

- Wed: The War for Mobile Phones Lost

- Thu: The Battle for Tablets

- Fri: Picking Your Battles Is As Important as Winning Them

4) The Battle For Tablets

If Android’s battle for phones is a Pyrrhic victory, Android’s battle for tablets is a flat-out ignominious defeat.

Android’s Strategic Tablet Blunder

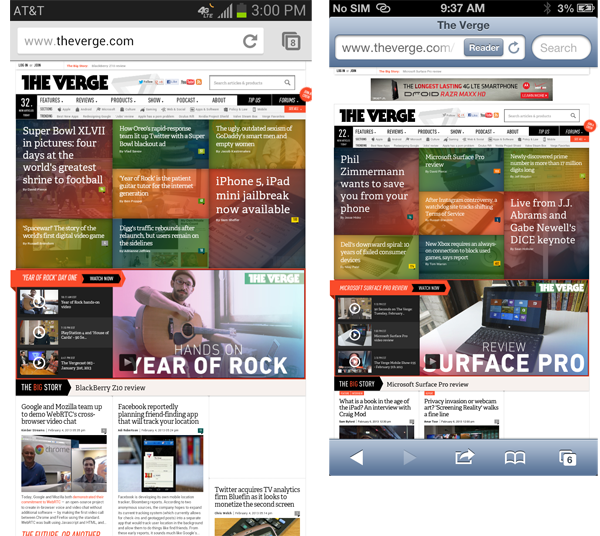

The tablet’s larger screen size demands that developers create apps optimized just for its form factor. This makes tablets a seperate platform all its own. Google’s big mistake in tablets was that they either didn’t recognize or refused to acknowledge that fact.

Google just saw tablets as big phones and acted accordingly. Rather than focusing on the creation of tablet optimized apps, Google encouraged their developers to create one-size-fits-all apps. Developers were encouraged to focus on scalability rather than optimization.

Google made their mind set clear by refusing to even establish a separate tablet-optimized classification for their store. While their nearest competitor highlighted the fact that they had 250,000 tablet optimized apps, Google categorically denied that there was any difference at all between phone and tablet apps. The result has mostly been a lot of Android phone apps awkwardly stretched to fit the larger tablet screen. Even big name apps like Twitter and Rdio looked unwieldy on Android tablets.

As recently as June 2012, when the Nexus 7 was introduced, Google Senior Vice President Andy Rubin reaffirmed that Google was sticking with its strategy of encouraging developers to write a single app for both phones and tablets.

“I don’t think there should be apps specific to a tablet…if someone makes an ICS app it’s going to run on phones and it’s going to run on tablets.” ~ Andy Rubin

Google’s policy was focused on the developer, not the consumer. It allowed developers to create apps that worked on more devices, but it did so at the expense of the user experience.

Andy Rubin went on to admit that he was upset that Android tablets weren’t selling. After looking into the reasons, Rubin declared that Google had discovered the reason for the lack of sales. While hardware really mattered on phones, consumers bought into content ecosystems with tablets. Rubin said that Google had lacked some of the ecosystem pieces that were necessary – such as TV shows, movies, magazines, etc. – to make people want to consume on a tablet.

“I think that was the missing piece,” Rubin said.

Do you hear what Rubin was saying? In his mind – and presumably in the mind of all of Google – the reason that Android tablets weren’t selling was because of a lack of compelling CONTENT. Tablet optimized apps never entered into the proposed “solution” to Android’s tablet woes. The Nexus 7 was all about content delivery since – in their minds – it was content, not apps, that was the missing piece.

Finally Google reversed course. On October 18, 2012, Google published a “tablet app quality checklist” on its Android Developer website and began to seriously urge developers to build tablet-optimized apps.Two and a half-years late and 250,000 iOS tablet optimized apps later, Google finally gets it – tablet optimized apps DO matter.

Or do they get it? Google STILL isn’t asking developers to make separate phone and tablet versios of their apps. And they STILL don’t separate phone apps from tablet apps in their store. And when asked why there still aren’t many tablet-sized apps for Android, Director for Android Partnerships, John Lagerling, said:

But before, I’ll be honest and say, yes, there was a lack of tablet apps that supported bigger screen real estate. But I’ll add that, I know we talked about the Cupertino guys, but obviously people who have smartphones are a huge target for us. If you look globally that’s something we worry more about, not so much about competing with other smartphones, but more about, how can we get more people onto the Internet on mobile phones? And that’s a big deal. That’s why low cost is so important.

Translation: Smartphones are more important to us than tablets and market share is more important to us than anything.

No wonder Android’s tablet efforts continue to languish.

Android Tablet Sales

So how is that one-size-fits-all, let’s-not-optimize-apps-to-the-tablet strategy working out for Android? The results speak for themselves.

At last report, tablets were just 5.38% of Android’s daily activations. And Nexus 7 sales – although constantly referred to as a “success” in the tech media – have been humble, to say the least.

Mark Mahaney, who follows Google for Citi Research … thinks Google sold about a million units of their tablet (that is made by Asus) and that accounts for about $200 million in revenue.

Ben Schachter of McQuarie Securities agrees and estimates that Nexus 7 sales accounted for probably $150 million to $200 million…in… revenue.

Piper Jaffray’s Gene Muster estimates that Google sold between 800,000 to a million units, while Doug Anmuth of JP Morgan says Google sold about 700,000 units of Nexus 7 tablets.

Asustek CFO David Chang told the WSJ that the company was selling—not just shipping—500,000 units a month initially, when the Nexus 7 launched in July. Figures bumped up to 600,000-700,000 in the following months, and in “this latest month,” Google and Asus have sold close to one million units, said Chang.

Let me put those numbers in perspective.

The Nexus 7 may have made as little as 200 million – in revenue, not profit – in an entire quarter. That’s pathetic.

And we know that Google didn’t make any profits from the sales of the Nexus 7 because they told us so.

“When it gets sold through the Play store, there’s no margin,” Rubin said. “It just basically gets (sold) through.”

But revenue and profits really don’t matter in a subsidized model. The concept is to get as many units on the market as possible in order to enhance the opportunities to sell content and advertising. So let’s look at the Nexus 7’s sales numbers.

The Nexus 7’s sales are either as high as 1 million units a month or as low as 1 million, 800,000 or 700,000 units a quarter. And the reason we’re relying on estimates is because Google refuses to release actual sales numbers – which is telling all in itself.

By way of contrast, Apple sold a total of 3 million iPad Minis and iPad 4’s in their first three days of availaility. At its current pace, the Nexus 7 would take between 3 months to 3 quarters to even match, let alone exceed, the number of tablets sold by Apple’s first 3 days of sales.

- SUBSIDIZED BUSINESS MODELS THRIVE ON VOLUME

Those sales numbers are bad enough, but for a subsidized product, they’re gawdawful. Remember, the Nexus 7 is being given away at cost. Can you imgagine how many more cars or televisions would be sold if they were being sold at cost? The Nexus 7’s should be selling like crazy, not badly trailing competitive offerings that cost $300 more.

This is a give-away-the-razor, sell-the-blade business model. (See my article entitled: “Selling The Amazon Kindle Fire and Google Nexus 7 Is As Silly As Selling Razor Blades To Men Who Love Beards“). Giving away the razor does not guarantee the sale of the blade but NOT giving away the razor DOES guarantee that the blades won’t be sold. Simiarly, volume sales of Nexus tablets do not guarantee that Google will profit from the sale of content and ads but low volume sales DO guarantee that they will not.

Pundits are opining that the Nexus 7’s lower price will make it a hot selling item for the holiday quarter. And I have no doubt that sales will increase. But if Google was having trouble selling the Nexus 7 when its only competition was the 7 inch Kindle Fire and the 10 inch Apple iPad, then why does anyone seriously think it will do significantly better now that it also has to compete with the Apple iPad Mini and the Microsoft Surface?

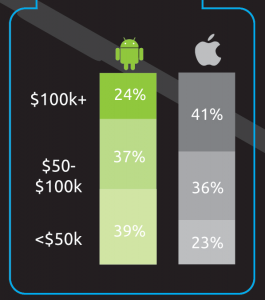

Android Irony: Tablets Are Where The Ad Revenue Is

The irony in all of this is that tablets are where the ad revenue is. Android has fought and won the battle for phones but phones don’t produce much ad revenue. Meanwhile, Android has ignored tablets and tablets hold the prize that they were so desperately seeking all along. Like a General who is a great tactician but a poor strategist, Android has won all of the battles that they’ve fought, but they’ve fought all of their battles in the wrong places.

- TABLETS ARE MORE VALUABLE

Studies have shown that tablet users are the more valuable consumers for advertisers to reach compared with PC and phone users. Tablet users spend 30 percent more time on sites and have 20 percent higher engagement.

“We found it interesting that tablets also had a smaller percentage of users who adopted ‘do not track’ settings compared to PC users,” Mr. Barnette said. “Mobile had the highest percentage of users who adopt do not track at 60 percent.”

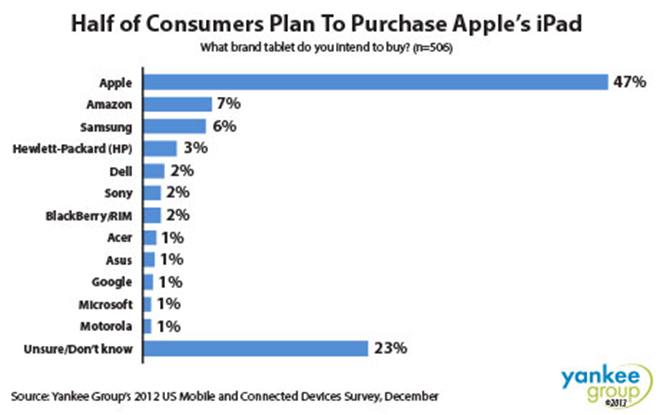

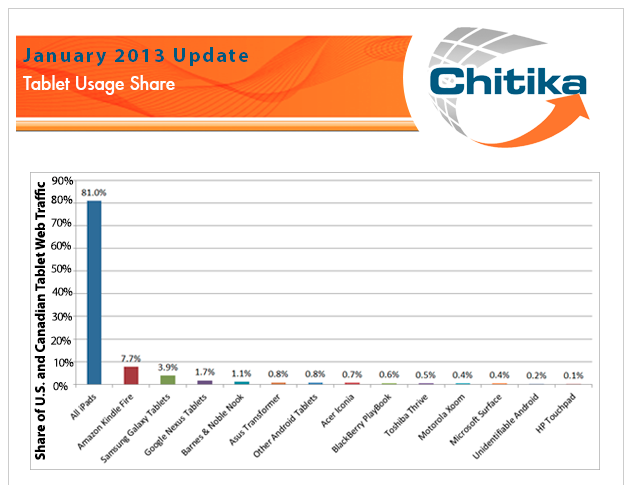

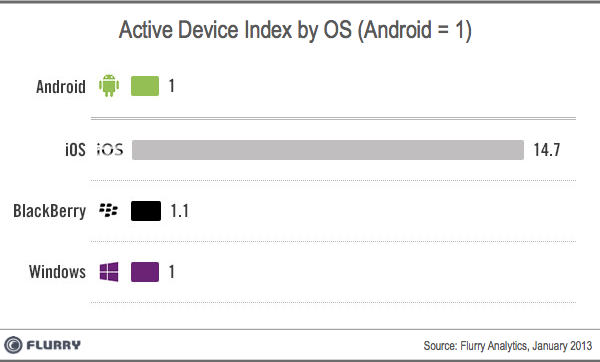

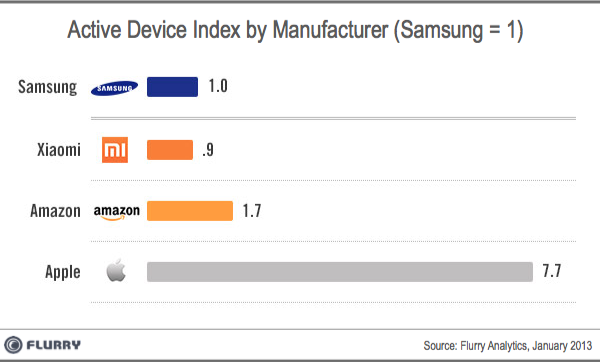

- APPLE IS DOMINATING TABLETS

And while tablets are dominating mobile revenues, Apple is dominating tablets.

The iPad accounts for between 91% and 98% of web traffic for all tablets. That only leaves 2% to 9% total web traffic for every other type of tablet combined.

And Apple dominates tablet downloads too.

“We estimate in the first half of this year the iPad saw over five times more app downloads than all Android tablets combined.”

- TABLETS AD SPENDING OUTWEIGHS SMARTPHONE AD SPENDING

And in the absolute kicker, it is anticipated that tablet ad spending will outweigh smartphone ad spending this holiday season.

Think for a moment just how crazy that is. The ads for all the Android, iOS, Windows Phone 7 and every other smartphone combined will be outsold by the ads sold on tablets this holiday season. Wow.

Next

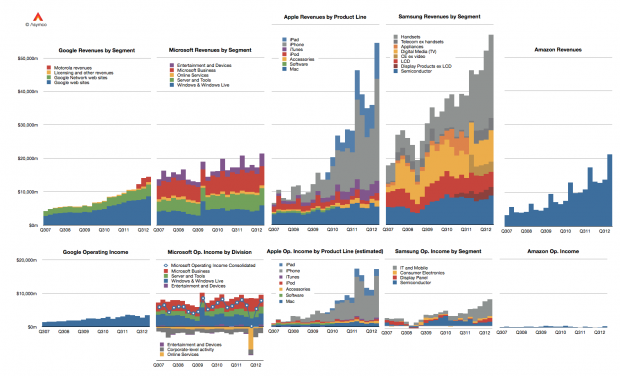

Google has won the battle for the desktop. Android has won the battle for the phone. But Google’s prospects are possibly worse today than they were when they embarked on their Android strategy. Tomorrow we sum it all up and look to the future in the final article of the series entitled:

“Picking Your Battles Is As Important as Winning Them”