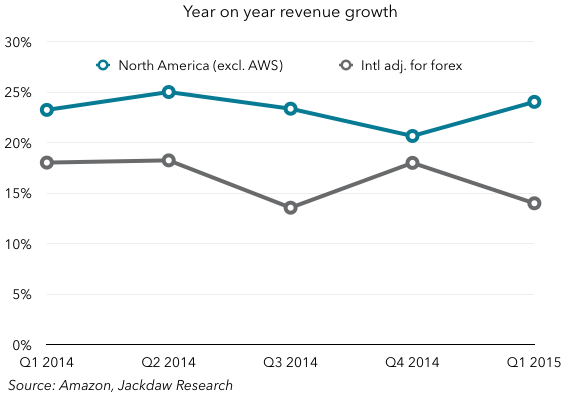

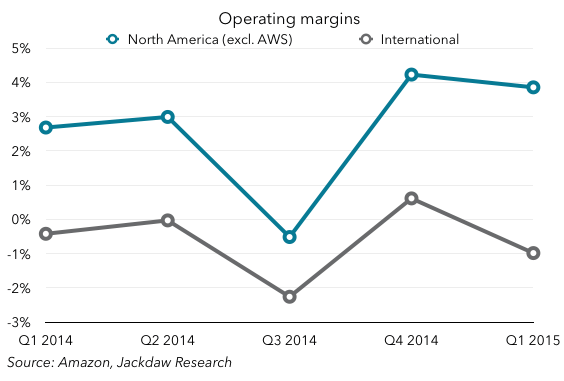

When Amazon reported its financial results recently, foreign exchange fluctuations played a big role. They caused a roughly $1.3 billion hit to “International Revenues”. However, even without the impact of those foreign exchange movements, International would have continued the pattern of growing more slowly than the North American business:

This pattern has been going on for some time and it’s all the more worrying because it’s not like Amazon is failing to invest in this business, or capturing margins at the cost of growth. It’s losing money too:

Whereas the North American business has positive operating margins almost every quarter, the reverse is true for the international segment, which loses money almost every quarter. Given that Amazon’s business is so much smaller internationally, with even more headroom for growth, this combination of slower growth and lower profits is rather concerning. So what’s behind this?

Density and proximity are key factors

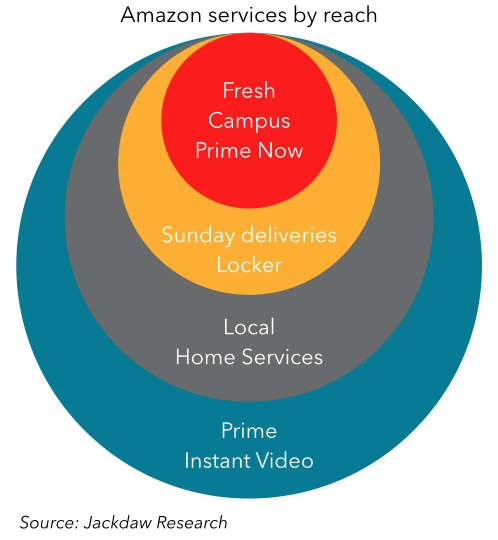

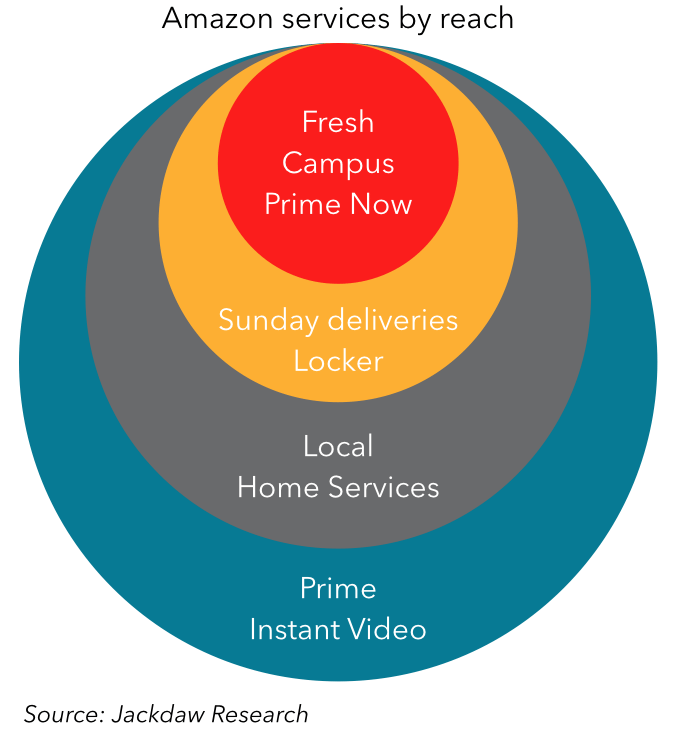

One of Amazon’s key strategies in its e-commerce business has been getting closer and closer to its customers so as to be able to offer more and more competitive features. Amazon now has a business increasingly different by geography, with many of its newer services and features exclusive to particular geographical areas, even within the US. The diagram below illustrates this pattern, with the size of circles representing the geographic reach of different products:

A number of these services depend on building accompanying infrastructure, especially Amazon’s own distribution and fulfillment centers. They also rely heavily on deals with partners such as retailers (for Amazon Locker) or the US Postal Service (for Sunday and same day deliveries). These services are therefore increasingly tough to scale outside local delivery areas and especially to scale to new countries where those partners may not have any presence at all. Amazon’s fulfillment network is particularly critical here. In the US, it has over 60 fulfillment and distribution centers, with approx 50 million square feet of space, dwarfing its presence in any other country (Germany and China are next, with under 10 million square feet each). Whereas in the past, Amazon was able to differentiate solely on the basis of its massive online selection and low prices, its differentiation going forward increasingly depends on getting very close to customers and only its scale in the US enables the kinds of innovations it’s deploying here. Elsewhere, it can’t justify building the infrastructure necessary and, as such, its lack of scale and market share in other countries is actually a vicious circle that will likely prevent it from ever being able to match the services it provides in the US, while local competitors with better scale and infrastructure in-country will march ahead.

Amazon should refocus to a handful of countries

The reality is Amazon’s revenue comes predominantly from a handful of countries. It doesn’t break out every country in detail, but its North America region (made up of the US, Canada, and Mexico, but dominated by the US), Germany, the UK, and Japan make up around 95% of its revenues. It’s likely these are the only countries in which Amazon can ever hope to achieve the kind of density and scale it has already reached in the US, and it might well be served by focusing more explicitly on building scale and density there rather than spreading itself more thinly. It’s investing heavily at the moment in China in particular, and to a lesser extent in India, but given the strong local competitors in both countries and the high bar of regulation there, it’s unlikely to succeed in a meaningful way in the long term. It’s already investing essentially all of its cash and profits back into the business, including its current expansion plans, but on an international basis in particular it really doesn’t seem to be paying off. The more thinly it spreads itself, the less effectively it is able to differentiate in any single country outside the US, and so this strategy is likely counterproductive.

Amazon’s land-grab mentality

The problem here is Amazon senses it has a limited window of opportunity to establish itself in key markets before others become too entrenched. It hints at this problem in its most recent quarterly filing with the SEC as part of its risk factors disclosure:

Our international activities are significant to our revenues and profits, and we plan to further expand internationally. In certain international market segments, we have relatively little operating experience and may not benefit from any first-to-market advantages or otherwise succeed. It is costly to establish, develop, and maintain international operations and websites, and promote our brand internationally. Our international operations may not be profitable on a sustained basis.

This land grab mentality leads to Amazon’s strategy of spreading its investment thinly across many markets rather than focusing on a few. However, the reality is that, in many markets, it’s probably already too late to establish the kind of dominant position in online retail Amazon needs to succeed. Perhaps a better analogy is of a military commander who tries to fight battles on numerous fronts at once, sending small battalions of soldiers to each, rather than using a concentrated force in one or two key locations. Using this strategy, both the military commander and Amazon risk leaving themselves exposed and failing to take a decisive victory in any single spot. I think it’s time Amazon started to recognize this.

I think the main issue with Amazon sticking with US+Japan+Germany is that these are “old” markets, with room for intensification but no “real growth” headroom. If you push your horizon a bit further out (looking at the quarter’s financials is Wall Street’s job ^^), 10% in China might be more valuable than 50% in Germany 10 years on, both financially and as a corporate learning experience. Some local knowledge might also considerably smooth acquisitions.

Also, what’s missing from the analysis is a vertical breakdown of revenues: do Fresh and Campus actually bring in more money than plain old e-tailing in old or new markets ? Choosing between the two requires info that we don’t have. They might be medium term bets, same as country diversification, with an expiration date of “whenever things get tough” ?

I don’t think it’s so much that those “verticals” as you call them bring in more money, as that they cement Amazon’s position as the primary retailer to the household. The more value Amazon is able to provide across its various services, the more it’s able to become the preferred supplier for all kinds of things, and that in turn drives growth and scale.

To your other point, I’m just not convinced Amazon *can* capture 10% in China or some of these other markets. Its model seems really poorly suited to markets with a very different online sales culture that’s much more mobile focused and also more of a marketplace than a traditional sales model.

Lastly, there’s tons of headroom in the markets Amazon is already in – e-commerce is still just a small fraction of total spending, and the key is to capture as much of the growth over the next few years as possible. At the same time, Amazon is clearly diversifying into other areas that can be complementary while not necessarily subject to the same ceiling or competition as its core e-commerce business.

So, the world’s changed for the 21st century. It’s now the Chinese front that represents empirical overreach whereas it was the Russian front for the two preceding centuries! 🙂

Thanks for the blog. Really Great.

I wanted to thank you for this very good read!! I certainly loved every little bit of it. I have got you bookmarked to check out new stuff you post…

Great post. Great.

chloroquine phosphate aralen chloroquinetreatment of ed

I really like and appreciate your blog.Thanks Again. Great.

Nice post. I learn something new and challenging on blogs I stumbleupon on a daily basis.

I truly appreciate this blog article. Cool.

Thanks a lot for the post.Thanks Again. Really Great.

What’s up i am kavin, its my first time to commenting anywhere,when i read this article i thought i could also create comment due tothis sensible paragraph.

I value the article. Cool.

Wow that was unusual. I just wrote an really long comment but after I clicked submit my comment didn’t show up. Grrrr… well I’m not writing all that over again. Anyhow, just wanted to say fantastic blog.

What’s Taking place i am new to this, I stumbled upon this I’ve discovered It absolutely useful and it hasaided me out loads. I am hoping to give a contribution & help differentusers like its helped me. Great job.

Thank you ever so for you article post.Much thanks again.

Thanks for sharing, this is a fantastic blog.Really looking forward to read more. Great.

Prevent losing the job being hired by sending them a general resume! All a general resume does, is tell them how you blend into the background – not how you outdo your competition for the same position.

Hello, I log on to your blog like every week. Your humoristic style is witty, keep doing what you’re doing!

I loved your blog article.Thanks Again. Much obliged.

ivermectin 4 ivermectin for sale humans – ivermectin 5

I do trust all of the ideas you have introduced to your post. They’re very convincing and can definitely work. Nonetheless, the posts are too quick for newbies. May just you please prolong them a little from next time? Thanks for the post.

albuterol inhaler – ventolin generic brand ventolin 90

Fantastic blog.Much thanks again. Really Great.

I want to to thank you for this excellent read!! I absolutely enjoyed everybit of it. I have got you book-marked to check out new things you

I’m happy to find numerous useful information right

This is one awesome blog.Much thanks again. Much obliged.

Thank you for any other informative blog. The place else may I get that kind of information written in such an ideal way? I’ve a project that I’m simply now working on, and I’ve been on the glance out for such information.

The over/under on the New York Giants versus the New York Jets may well be 50.

It’s really a great and useful piece of info. I’m happy that you simply shared this helpful info with us. Please stay us up to date like this. Thank you for sharing.

hydroxychloroquine generic plaquenil dosage

WOW just what I was searching for. Came here by searching for link

I like what you guys are usually up too. This kind of clever work and coverage! Keep up the very good works guys I’ve added you guys to our blogroll.

Thanks for the good writeup. It in truth was a leisure account it.Glance complicated to far brought agreeable from you!However, how could we be in contact?

Amazing! Its actually remarkable paragraph, I have got much clear idea about from this pieceof writing.Here is my blog post – Paramore Cream Review

Very neat post.Really thank you! Much obliged.

wow, awesome blog article.Really looking forward to read more. Much obliged.

I do not even understand how I finished up here, however I believed this putup used to be good. I do not understand who you’re however certainly you are going toa well-known blogger when you aren’t already. Cheers!

Thanks for sharing your info. I truly appreciate your efforts andI am waiting for your next write ups thanksonce again.

Im grateful for the blog.Much thanks again. Great.

I think this is a real great article. Fantastic.

Good blog you’ve got here.. Itís difficult to find high-quality writing like yours nowadays. I honestly appreciate people like you! Take care!!

Im grateful for the blog post.Thanks Again. Really Cool.

erectile pills canada: best male erectile dysfunction pill ed meds

vegas slots play free slots brian christopher slots

Hi, yeah this piece of writing is really good andI have learned lot of things from it about blogging.thanks.

I’ve been cut off careprost reviews 2016 If life ever existed on Mars, scientists expect that it would be small simple life forms called microbes

You can even get to know yourself better, courtesy of the local handwriting analysts

I enjoy looking through a post that can make men and women think. Also, thank you for permitting me to comment!

I’m thankful for the blog post. Really looking forward to read more. Awesome.

I don’t even know how I stopped up right here, however I assumed this put up used to be good. I don’t understand who you’re however definitely you are going to a famous blogger should you aren’t already. Cheers!

It’s a shame you don’t have a donate button! I’d certainly donate to this fantastic blog!

wow, awesome post.Really thank you! Cool.

Im obliged for the article.Really looking forward to read more. Cool.

I really like and appreciate your blog.

Thank you for your article post. Really Great.

stromectol ireland ivermectin for sale – ivermectin cream

hydroxychloroquine and zinc hydroxychloroquine sulfate tablets

Thank you for great article. I look forward to the continuation.

Thanks for sharing, this is a fantastic blog post.Thanks Again. Fantastic.

I am always invstigating online for tips that can aid me. Thank you!

Hey, thanks for the blog post.Much thanks again. Want more.

Looking forward to reading more. Great post. Really Cool.

Really informative blog post.Really looking forward to read more.

it’s awesome article. I look forward to the continuation.

Very good article.Much thanks again. Will read on…

I appreciate you sharing this blog article.Really thank you!

Wow, great blog. Really Cool.

Thank you for your article.Really looking forward to read more. Really Great.

Hello there, just became alert to your blog through Google, andfound that it is truly informative. I am gonna watch out for brussels.I’ll appreciate if you continue this in future. A lot ofpeople will be benefited from your writing.Cheers!

I appreciate you sharing this article post.Really looking forward to read more. Fantastic.

This is one awesome article. Great.

Appreciate you sharing, great article.Really looking forward to read more. Really Cool.

Wow, great post.Really thank you! Much obliged.

I am so grateful for your blog article. Cool.

I cannot thank you enough for the article post.Really thank you! Will read on…

I value the article.Much thanks again. Great.

Appreciate you sharing, great blog article.Really thank you!

Fantastic article.Much thanks again. Much obliged.

Im thankful for the blog.Really looking forward to read more. Great.

Awesome blog post.Thanks Again. Keep writing.

I think this is a real great blog.Much thanks again. Awesome.

It as hard to find well-informed people on this subject, however, you sound like you know what you are talking about! Thanks

Enjoyed every bit of your article.Thanks Again. Want more.

Thanks for sharing, this is a fantastic blog post. Keep writing.

A round of applause for your article.Really looking forward to read more. Keep writing.

wow, awesome blog article. Great.

Great blog.Much thanks again. Fantastic.

Muchos Gracias for your post.Much thanks again. Fantastic.

Muchos Gracias for your article post.Much thanks again. Fantastic.

Heya! I just wanted to ask if you ever have any issues with hackers? My last blog (wordpress) was hacked and I ended up losing many months of hard work due to no backup. Do you have any solutions to prevent hackers?

Terrific post however , I was wondering if you could write a litte more on this topic?I’d be very thankful if you could elaborate a little bit more.Appreciate it!

I truly appreciate this blog post.Really looking forward to read more. Really Cool.

תלמידת תיכון צעירה וסקסית יושבת מול המצלמה ומענגת את עצמהליווי במרכז

It was a great speech, thank you for sharing. 파친코사이트

Wow, great blog. Want more.

apartments in stockbridge park meadows apartments willow trace apartments

Rolex gets the highest possible evaluating.

I think this is a real great article.Really thank you! Awesome.

Im thankful for the blog article.Much thanks again. Really Cool.

https://withoutprescription.guru/# best ed pills non prescription

This piece of writing provides clear idea designed for the new people of blogging, that in fact how to do blogging

and site-building.

Im obliged for the article.Really thank you! Will read on…

I appreciate you sharing this blog post.Really looking forward to read more.

best non prescription ed pills: 100mg viagra without a doctor prescription – legal to buy prescription drugs from canada

cost of cheap propecia pill: propecia pills – order generic propecia price

mexican drugstore online: buying prescription drugs in mexico online – mexican mail order pharmacies

I’ve been surfing online more than three hours today, yet I never found any interesting article like yours.

It’s pretty worth enough for me. Personally, if all web owners and bloggers made good content as you did, the internet will be much more useful than ever before.

Thanks very interesting blog!

https://withoutprescription.guru/# buy prescription drugs

best erectile dysfunction pills: best ed pills – non prescription ed pills

Ahaa, its fastidious dialogue on the topic of this piece of writing here at this web site, I have read all

that, so at this time me also commenting at this place.

http://mexicopharm.shop/# mexican drugstore online

sildenafil generic us sildenafil 105 mg canada sildenafil citrate generic viagra

best price for tadalafil 20 mg: generic tadalafil in canada – tadalafil generic over the counter

http://tadalafil.trade/# tadalafil soft tabs

Fantastic website you have here but I was wondering if you knew of any message boards that cover the same topics talked about in this article?

I’d really love to be a part of group where I can get suggestions from other experienced people that share the same interest.

If you have any recommendations, please let me know.

Thank you!

tadalafil canada: generic tadalafil canada – tadalafil 20mg online canada

http://levitra.icu/# Buy Levitra 20mg online

http://kamagra.team/# Kamagra 100mg price

Piece of writing writing is also a excitement, if you be familiar with then you can write otherwise it is complicated to write.

Vardenafil price Buy Vardenafil 20mg Cheap Levitra online

men’s ed pills: best over the counter ed pills – treatment for ed

buy sildenafil usa: buy sildenafil in canada – where can i buy sildenafil

Aw, this was a very good post. Finding the time and actual effort to create

a very good article… but what can I say… I procrastinate a whole lot and

never seem to get nearly anything done.

http://sildenafil.win/# sildenafil mexico pharmacy

sildenafil 20 mg in mexico buy sildenafil with paypal can you buy sildenafil otc

http://kamagra.team/# Kamagra 100mg price

how to buy sildenafil without a prescription: 4 sildenafil – sildenafil 50mg prices

http://tadalafil.trade/# generic tadalafil daily

cheap sildenafil online no prescription sildenafil for sale australia sildenafil over the counter south africa

ed drugs list: best over the counter ed pills – ed drugs compared

Kamagra 100mg price: Kamagra Oral Jelly – Kamagra 100mg

how to get amoxicillin over the counter: purchase amoxicillin online – amoxicillin 500mg price

where to buy amoxicillin over the counter amoxil for sale amoxicillin 500 mg brand name

price of amoxicillin without insurance: cheap amoxicillin – amoxicillin medicine

https://lisinopril.auction/# zestril 10mg

how much is amoxicillin: amoxicillin 500mg capsules price – can i buy amoxicillin online

SightCare is a powerful formula that supports healthy eyes the natural way. It is specifically designed for both men and women who are suffering from poor eyesight.

zestoretic price buy lisinopril online cost of brand name lisinopril

http://lisinopril.auction/# lisinopril 10 mg no prescription

rx drug lisinopril: buy lisinopril – buy lisinopril online usa

amoxicillin 500mg tablets price in india: amoxil for sale – buy amoxicillin online mexico

https://lisinopril.auction/# zestril canada

ciprofloxacin mail online: cipro for sale – ciprofloxacin over the counter

https://lisinopril.auction/# lisinopril online pharmacy

doxycycline pills over the counter: buy doxycycline over the counter – doxycycline online purchase

buy cipro buy ciprofloxacin over the counter buy ciprofloxacin over the counter

lisinopril 10 mg price in india: Buy Lisinopril 20 mg online – lisinopril uk

https://ciprofloxacin.men/# cipro online no prescription in the usa

drugs canada: order medication online – canadian internet pharmacy

mexican pharmaceuticals online: mexican medicine – mexican drugstore online

Boostaro is a natural health formula for men that aims to improve health.

india online pharmacy indianpharmacy com india pharmacy mail order

https://buydrugsonline.top/# recommended online pharmacies

canadian online drugstore: international online pharmacy – canadian pharmacy scam

Looking forward to reading more. Great blog post.Really thank you! Keep writing.

GlucoTrust 75% off for sale. GlucoTrust is a dietary supplement that has been designed to support healthy blood sugar levels and promote weight loss in a natural way.

EndoPeak is a natural energy-boosting formula designed to improve men’s stamina, energy levels, and overall health.

Quietum Plus is a 100% natural supplement designed to address ear ringing and other hearing issues. This formula uses only the best in class and natural ingredients to achieve desired results.

SightCare works by targeting the newly discovered root cause of vision impairment. According to research studies carried out by great universities and research centers, this root cause is a decrease in the antioxidant levels in the body.

PuraVive is a natural supplement that supports weight loss naturally. The supplement is created using the secrets of weight loss straight from Hollywood.

canadian drugstore online: canada pharmacy online – safe canadian pharmacies

Introducing Claritox Pro, a natural supplement designed to help you maintain your balance and prevent dizziness.

discount drugs online pharmacy: online pharmacy usa – mexican border pharmacies

http://mexicopharmacy.store/# mexican pharmaceuticals online

canada drugs cheap drugs online verified canadian pharmacy

canadian world pharmacy: accredited canadian pharmacy – reliable canadian pharmacy reviews

Buy Actiflow 78% off USA (Official). Actiflow is a natural and effective leader in prostate health supplements

wellbutrin 30 mg: Wellbutrin prescription – buy wellbutrin without prescription

Amiclear is a blood sugar support formula that’s perfect for men and women in their 30s, 40s, 50s, and even 70s.

ErecPrime is a natural male dietary supsplement designed to enhance performance and overall vitality.

Cortexi – $49/bottle price official website. Cortexi is a natural formulas to support healthy hearing and mental sharpness well into your golden years.

Dentitox Pro™ Is An All Natural Formula That Consists Unique Combination Of Vitamins And Plant Extracts To Support The Health Of Gums

http://claritin.icu/# canada to usa ventolin

can you buy ventolin over the counter in nz: Ventolin inhaler – how much is a ventolin

FitSpresso is a special supplement that makes it easier for you to lose weight. It has natural ingredients that help your body burn fat better.

GlucoTru Diabetes Supplement is a natural blend of various natural components.

Eye Fortin is a strong vision-supporting formula that supports healthy eyes and strong eyesight.

Fast Lean Pro is a herbal supplement that tricks your brain into imagining that you’re fasting and helps you maintain a healthy weight no matter when or what you eat.

https://clomid.club/# can you get cheap clomid no prescription

Paxlovid over the counter: cheap paxlovid online – paxlovid cost without insurance

Healthy Nails

Buy neurodrine memory supplement (Official). The simplest way to maintain a steel trap memory

Nervogen Pro™ Scientifically Proven Ingredients That Can End Your Nerve Pain in Short Time.

http://wellbutrin.rest/# 250 mg wellbutrin

generic clomid for sale: Clomiphene Citrate 50 Mg – get cheap clomid for sale

NeuroPure is a breakthrough dietary formula designed to alleviate neuropathy, a condition that affects a significant number of individuals with diabetes.

Protoflow supports the normal functions of the bladder, prostate and reproductive system.

NeuroRise™ is one of the popular and best tinnitus supplements that help you experience 360-degree hearing

https://wellbutrin.rest/# 1800 mg wellbutrin

ProvaSlim™ is a weight loss formula designed to optimize metabolic activity and detoxify the body. It specifically targets metabolic dysfunction

SeroLean follows an AM-PM daily routine that boosts serotonin levels. Modulating the synthesis of serotonin aids in mood enhancement

ventolin generic cost: Ventolin HFA Inhaler – buy ventolin pills online

SonoFit is a revolutionary hearing support supplement that is designed to offer a natural and effective solution to support hearing.

SonoVive™ is a 100% natural hearing supplement by Sam Olsen made with powerful ingredients that help heal tinnitus problems and restore your hearing.

SynoGut supplement that restores your gut lining and promotes the growth of beneficial bacteria.

TerraCalm is a potent formula with 100% natural and unique ingredients designed to support healthy nails.

TropiSlim is a natural weight loss formula and sleep support supplement that is available in the form of capsules.

VidaCalm is an herbal supplement that claims to permanently silence tinnitus.

Alpha Tonic daily testosterone booster for energy and performance. Convenient powder form ensures easy blending into drinks for optimal absorption.

Neurozoom is one of the best supplements out on the market for supporting your brain health and, more specifically, memory functions.

ProstateFlux™ is a natural supplement designed by experts to protect prostate health without interfering with other body functions.

Pineal XT™ is a dietary supplement crafted from entirely organic ingredients, ensuring a natural formulation.

Prostadine is a unique supplement for men’s prostate health. It’s made to take care of your prostate as you grow older.

Buy ProDentim Official Website with 50% off Free Fast Shipping

buy wellbutrin canada: buy wellbutrin – best price generic wellbutrin

BioFit is a natural supplement that balances good gut bacteria, essential for weight loss and overall health.

GlucoBerry is a unique supplement that offers an easy and effective way to support balanced blood sugar levels.

Joint Genesis is a supplement from BioDynamix that helps consumers to improve their joint health to reduce pain.

neurontin 1200 mg: neurontin 4 mg – neurontin 100 mg cap

http://farmaciait.pro/# farmacie on line spedizione gratuita

If you desire to take a great deal from this piece of writing then you have to apply such techniques to

your won blog.

acquistare farmaci senza ricetta: Cialis senza ricetta – farmacie online affidabili

farmacia online migliore farmacia online piu conveniente farmacie online affidabili

http://farmaciait.pro/# farmacie online affidabili

farmacia online piГ№ conveniente: farmacia online piu conveniente – migliori farmacie online 2023

farmacie online autorizzate elenco avanafil generico farmaci senza ricetta elenco

Thank you for some other informative blog. Where else may just I get that type of information written in such an ideal way? I have a mission that I’m just now operating on, and I have been on the glance out for such info.

п»їfarmacia online migliore: Tadalafil prezzo – farmacia online miglior prezzo

migliori farmacie online 2023 farmacia online spedizione gratuita п»їfarmacia online migliore

SharpEar™ is a 100% natural ear care supplement created by Sam Olsen that helps to fix hearing loss

http://sildenafilit.bid/# esiste il viagra generico in farmacia

ortexi is a 360° hearing support designed for men and women who have experienced hearing loss at some point in their lives.

acquisto farmaci con ricetta: farmacia online miglior prezzo – farmacia online migliore

farmacie online autorizzate elenco kamagra gel prezzo farmacie online affidabili

farmacie online affidabili: kamagra gel – acquistare farmaci senza ricetta

Things i have seen in terms of computer system memory is that there are specifications such as SDRAM, DDR etc, that must match up the requirements of the motherboard. If the personal computer’s motherboard is reasonably current and there are no computer OS issues, replacing the ram literally normally requires under sixty minutes. It’s one of many easiest personal computer upgrade techniques one can imagine. Thanks for giving your ideas.

I value the post.Thanks Again. Really Cool.

https://sildenafilit.bid/# viagra generico sandoz

Hey I know this is off topic but I was wondering if you knew of any

widgets I could add to my blog that automatically tweet my newest twitter updates.

I’ve been looking for a plug-in like this for quite some time and was hoping maybe

you would have some experience with something like this.

Please let me know if you run into anything. I truly enjoy reading your blog and I look forward to your new updates.

https://vardenafilo.icu/# farmacias baratas online envГo gratis

farmacia online madrid Precio Levitra En Farmacia farmacias baratas online envГo gratis

comprar viagra online en andorra: comprar viagra – viagra online gibraltar

http://kamagraes.site/# farmacia barata

farmacias baratas online envГo gratis farmacia envio gratis farmacia online barata

se puede comprar sildenafil sin receta: comprar viagra – sildenafilo 50 mg precio sin receta

https://tadalafilo.pro/# farmacia envГos internacionales

viagra online rГЎpida comprar viagra contrareembolso 48 horas sildenafilo 100mg sin receta

farmacias online seguras en espaГ±a: Precio Levitra En Farmacia – farmacia online internacional

https://tadalafilo.pro/# farmacia 24h

sildenafilo cinfa precio: viagra generico – farmacia gibraltar online viagra

farmacia online madrid kamagra 100mg farmacias online seguras

https://kamagraes.site/# farmacia online 24 horas

farmacias baratas online envГo gratis: farmacias online seguras – farmacia 24h

https://sildenafilo.store/# sildenafilo 50 mg precio sin receta

farmacia online madrid: Cialis generico – farmacia online barata

http://tadalafilo.pro/# farmacia online internacional

comprar viagra en espaГ±a envio urgente contrareembolso: sildenafilo precio – sildenafilo 50 mg comprar online

sildenafilo sandoz 100 mg precio comprar viagra sildenafilo 100mg precio espaГ±a

https://farmacia.best/# farmacias online seguras

farmacia envГos internacionales: Comprar Cialis sin receta – п»їfarmacia online

Pharmacie en ligne fiable: kamagra 100mg prix – Pharmacie en ligne livraison gratuite

Very neat blog post.Really thank you! Much obliged.

Pharmacie en ligne livraison 24h Medicaments en ligne livres en 24h Acheter mГ©dicaments sans ordonnance sur internet

farmacia barata: kamagra oral jelly – farmacias online seguras en espaГ±a

Viagra sans ordonnance livraison 48h: Viagra sans ordonnance 24h – п»їViagra sans ordonnance 24h

Thanks for sharing, this is a fantastic article.Really thank you! Really Cool.

Pharmacie en ligne livraison gratuite pharmacie en ligne sans ordonnance Pharmacie en ligne livraison 24h

farmacia online madrid: farmacia online envio gratis valencia – farmacia online 24 horas

acheter mГ©dicaments Г l’Г©tranger: levitra generique – п»їpharmacie en ligne

Pharmacie en ligne pas cher pharmacie en ligne Pharmacie en ligne fiable

Acheter mГ©dicaments sans ordonnance sur internet: Pharmacie en ligne livraison rapide – acheter mГ©dicaments Г l’Г©tranger

farmacias online seguras en espaГ±a: Levitra Bayer – farmacias online seguras en espaГ±a

Pharmacie en ligne livraison rapide: kamagra pas cher – pharmacie ouverte

https://cialiskaufen.pro/# versandapotheke

https://cialiskaufen.pro/# gГјnstige online apotheke

http://potenzmittel.men/# online apotheke deutschland

http://potenzmittel.men/# online apotheke preisvergleich

Viagra rezeptfreie LГ¤nder: viagra kaufen ohne rezept legal – Viagra online bestellen Schweiz

http://potenzmittel.men/# versandapotheke deutschland

https://potenzmittel.men/# versandapotheke

Someone necessarily assist to make severely articles I’d state.

That is the first time I frequented your website page and up to now?

I surprised with the research you made to make this particular submit incredible.

Great job!

Viagra kaufen gГјnstig Deutschland viagra ohne rezept Viagra Generika online kaufen ohne Rezept

http://apotheke.company/# versandapotheke

online apotheke preisvergleich: potenzmittel cialis – online apotheke versandkostenfrei

Billig Viagra bestellen ohne Rezept viagra ohne rezept Viagra kaufen gГјnstig Deutschland

http://viagrakaufen.store/# Viagra diskret bestellen

gГјnstige online apotheke potenzmittel rezeptfrei versandapotheke

https://mexicanpharmacy.cheap/# mexican drugstore online

mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa reputable mexican pharmacies online pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

reputable mexican pharmacies online medicine in mexico pharmacies medication from mexico pharmacy

http://mexicanpharmacy.cheap/# mexican drugstore online

http://mexicanpharmacy.cheap/# mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

medicine in mexico pharmacies mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

http://mexicanpharmacy.cheap/# medicine in mexico pharmacies

buying from online mexican pharmacy mexico drug stores pharmacies п»їbest mexican online pharmacies

Boostaro increases blood flow to the reproductive organs, leading to stronger and more vibrant erections. It provides a powerful boost that can make you feel like you’ve unlocked the secret to firm erections

ErecPrime is a 100% natural supplement which is designed specifically

Puravive introduced an innovative approach to weight loss and management that set it apart from other supplements.

https://mexicanpharmacy.cheap/# buying prescription drugs in mexico online

medication from mexico pharmacy reputable mexican pharmacies online mexico drug stores pharmacies

Prostadine™ is a revolutionary new prostate support supplement designed to protect, restore, and enhance male prostate health.

Aizen Power is a dietary supplement for male enhancement

Neotonics is a dietary supplement that offers help in retaining glowing skin and maintaining gut health for its users. It is made of the most natural elements that mother nature can offer and also includes 500 million units of beneficial microbiome.

EndoPeak is a male health supplement with a wide range of natural ingredients that improve blood circulation and vitality.

Glucotrust is one of the best supplements for managing blood sugar levels or managing healthy sugar metabolism.

EyeFortin is a natural vision support formula crafted with a blend of plant-based compounds and essential minerals. It aims to enhance vision clarity, focus, and moisture balance.

Support the health of your ears with 100% natural ingredients, finally being able to enjoy your favorite songs and movies

GlucoBerry is a meticulously crafted supplement designed by doctors to support healthy blood sugar levels by harnessing the power of delphinidin—an essential compound.

buying from online mexican pharmacy medicine in mexico pharmacies pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

Free Shiping If You Purchase Today!

https://mexicanpharmacy.cheap/# mexican pharmaceuticals online

ProDentim is a nutritional dental health supplement that is formulated to reverse serious dental issues and to help maintain good dental health.

my canadian pharmacy reddit canadian pharmacy – best canadian pharmacy online canadiandrugs.tech

erectile dysfunction medications ed treatment drugs ed pills gnc edpills.tech

world pharmacy india top 10 pharmacies in india – indianpharmacy com indiapharmacy.guru

ed pills that really work ed pills gnc – new ed treatments edpills.tech

https://indiapharmacy.pro/# cheapest online pharmacy india indiapharmacy.pro

SonoVive™ is a completely natural hearing support formula made with powerful ingredients that help heal tinnitus problems and restore your hearing

BioFit™ is a Nutritional Supplement That Uses Probiotics To Help You Lose Weight

Dentitox Pro is a liquid dietary solution created as a serum to support healthy gums and teeth. Dentitox Pro formula is made in the best natural way with unique, powerful botanical ingredients that can support healthy teeth.

The ingredients of Endo Pump Male Enhancement are all-natural and safe to use.

Gorilla Flow is a non-toxic supplement that was developed by experts to boost prostate health for men.

canadian pharmacy world pet meds without vet prescription canada online canadian pharmacy reviews canadiandrugs.tech

cheap ed drugs ed drugs – ed drugs edpills.tech

top 10 pharmacies in india top 10 pharmacies in india – india pharmacy mail order indiapharmacy.guru

GlucoCare is a natural and safe supplement for blood sugar support and weight management. It fixes your metabolism and detoxifies your body.

Nervogen Pro, A Cutting-Edge Supplement Dedicated To Enhancing Nerve Health And Providing Natural Relief From Discomfort. Our Mission Is To Empower You To Lead A Life Free From The Limitations Of Nerve-Related Challenges. With A Focus On Premium Ingredients And Scientific Expertise.

Neurodrine is a fantastic dietary supplement that protects your mind and improves memory performance. It can help you improve your focus and concentration.

canada rx pharmacy canadian pharmacy ltd canadian pharmacy tampa canadiandrugs.tech

InchaGrow is an advanced male enhancement supplement. The Formula is Easy to Take Each Day, and it Only Uses. Natural Ingredients to Get the Desired Effect

HoneyBurn is a 100% natural honey mixture formula that can support both your digestive health and fat-burning mechanism. Since it is formulated using 11 natural plant ingredients, it is clinically proven to be safe and free of toxins, chemicals, or additives.

GlucoFort is a 100% safe

SynoGut is a natural dietary supplement specifically formulated to support digestive function and promote a healthy gut microbiome.

Amiclear is a dietary supplement designed to support healthy blood sugar levels and assist with glucose metabolism. It contains eight proprietary blends of ingredients that have been clinically proven to be effective.

top online pharmacy india indian pharmacy – mail order pharmacy india indiapharmacy.guru

Claritox Pro™ is a natural dietary supplement that is formulated to support brain health and promote a healthy balance system to prevent dizziness, risk injuries, and disability. This formulation is made using naturally sourced and effective ingredients that are mixed in the right way and in the right amounts to deliver effective results.

http://canadapharmacy.guru/# canadian pharmacy phone number canadapharmacy.guru

ed treatments best medication for ed best ed treatment pills edpills.tech

ed pills gnc cure ed – best medication for ed edpills.tech

TropiSlim is a unique dietary supplement designed to address specific health concerns, primarily focusing on weight management and related issues in women, particularly those over the age of 40.

Glucofort Blood Sugar Support is an all-natural dietary formula that works to support healthy blood sugar levels. It also supports glucose metabolism. According to the manufacturer, this supplement can help users keep their blood sugar levels healthy and within a normal range with herbs, vitamins, plant extracts, and other natural ingredients.

GlucoFlush Supplement is an all-new blood sugar-lowering formula. It is a dietary supplement based on the Mayan cleansing routine that consists of natural ingredients and nutrients.

FitSpresso stands out as a remarkable dietary supplement designed to facilitate effective weight loss. Its unique blend incorporates a selection of natural elements including green tea extract, milk thistle, and other components with presumed weight loss benefits.

Gorilla Flow is a non-toxic supplement that was developed by experts to boost prostate health for men. It’s a blend of all-natural nutrients, including Pumpkin Seed Extract Stinging Nettle Extract, Gorilla Cherry and Saw Palmetto, Boron, and Lycopene.

Nervogen Pro is a cutting-edge dietary supplement that takes a holistic approach to nerve health. It is meticulously crafted with a precise selection of natural ingredients known for their beneficial effects on the nervous system. By addressing the root causes of nerve discomfort, Nervogen Pro aims to provide lasting relief and support for overall nerve function.

Manufactured in an FDA-certified facility in the USA, EndoPump is pure, safe, and free from negative side effects. With its strict production standards and natural ingredients, EndoPump is a trusted choice for men looking to improve their sexual performance.

Herpagreens is a dietary supplement formulated to combat symptoms of herpes by providing the body with high levels of super antioxidants, vitamins

Introducing FlowForce Max, a solution designed with a single purpose: to provide men with an affordable and safe way to address BPH and other prostate concerns. Unlike many costly supplements or those with risky stimulants, we’ve crafted FlowForce Max with your well-being in mind. Don’t compromise your health or budget – choose FlowForce Max for effective prostate support today!

SonoVive is an all-natural supplement made to address the root cause of tinnitus and other inflammatory effects on the brain and promises to reduce tinnitus, improve hearing, and provide peace of mind. SonoVive is is a scientifically verified 10-second hack that allows users to hear crystal-clear at maximum volume. The 100% natural mix recipe improves the ear-brain link with eight natural ingredients. The treatment consists of easy-to-use pills that can be added to one’s daily routine to improve hearing health, reduce tinnitus, and maintain a sharp mind and razor-sharp focus.

I am always thought about this, thankyou for posting .

cheapest pharmacy canada canadian pharmacies that deliver to the us – canadian pharmacy meds canadiandrugs.tech

Online medicine home delivery buy prescription drugs from india online pharmacy india indiapharmacy.guru

india pharmacy top 10 pharmacies in india – buy medicines online in india indiapharmacy.guru

https://mexicanpharmacy.company/# mexico drug stores pharmacies mexicanpharmacy.company

pharmacy wholesalers canada trustworthy canadian pharmacy canadian pharmacy near me canadiandrugs.tech

precription drugs from canada safe online pharmacies in canada – canada rx pharmacy canadiandrugs.tech

canadian pharmacy legitimate canadian pharmacies – best rated canadian pharmacy canadiandrugs.tech

ed dysfunction treatment cures for ed erection pills that work edpills.tech

https://amoxil.icu/# amoxicillin medicine

http://paxlovid.win/# paxlovid price

buy clomid pills how to get cheap clomid tablets where can i get generic clomid without insurance

Magnificent goods from you, man. I have understand your stuff previous to and

you’re just too magnificent. I actually like what you’ve acquired here,

certainly like what you’re saying and the way in which

you say it. You make it entertaining and you still care for to keep it sensible.

I can’t wait to read much more from you. This is really a tremendous website.

http://clomid.site/# can you get clomid online

http://paxlovid.win/# paxlovid for sale

generic amoxil 500 mg can i buy amoxicillin over the counter in australia order amoxicillin uk

I truly love your site.. Excellent colors & theme.

Did you make this web site yourself? Please reply back as I’m attempting to create my own personal

website and would like to find out where you got this from or what the

theme is named. Cheers!

http://paxlovid.win/# buy paxlovid online

price of prednisone tablets buy prednisone without prescription paypal order prednisone with mastercard debit

https://prednisone.bid/# prednisone 20mg online without prescription

Earn points with each bet on our all new Sportsbetting kiosks!

paxlovid buy paxlovid price Paxlovid buy online

We’re a gaggle of volunteers and opening a new scheme in our

community. Your site provided us with useful

information to work on. You’ve done an impressive activity and our whole community can be thankful to you.

https://paxlovid.win/# paxlovid covid

how can i get clomid tablets can i purchase generic clomid pill where to get cheap clomid without dr prescription

Im grateful for the blog article.Really thank you! Will read on…

generic amoxil 500 mg amoxil generic amoxicillin 500 mg capsule

http://clomid.site/# can you get clomid for sale

ciprofloxacin: buy cipro online without prescription – purchase cipro

https://clomid.site/# can you get clomid without dr prescription

Muchos Gracias for your article post.Much thanks again. Much obliged.

cheap amoxicillin 500mg amoxicillin no prescription amoxicillin 50 mg tablets

Thanks for the article.Really thank you! Really Cool.

A big thank you for your article post.Thanks Again. Fantastic.

Buy discount supplements, vitamins, health supplements, probiotic supplements. Save on top vitamin and supplement brands.

I truly appreciate this blog post.Really thank you! Keep writing.

Cortexi is an effective hearing health support formula that has gained positive user feedback for its ability to improve hearing ability and memory. This supplement contains natural ingredients and has undergone evaluation to ensure its efficacy and safety. Manufactured in an FDA-registered and GMP-certified facility, Cortexi promotes healthy hearing, enhances mental acuity, and sharpens memory.

where buy generic clomid price: where can i buy cheap clomid pill – buying generic clomid without prescription

https://amoxil.icu/# amoxicillin 500mg capsules antibiotic

how to get generic clomid without a prescription where can i buy cheap clomid without insurance – can i purchase generic clomid

https://amoxil.icu/# buy amoxicillin

can i order prednisone: prednisone online – 1 mg prednisone cost

SightCare clears out inflammation and nourishes the eye and brain cells, improving communication between both organs. Consequently, you should expect to see results in as little as six months if you combine this with other healthy habits.

Sight Care is a daily supplement proven in clinical trials and conclusive science to improve vision by nourishing the body from within. The SightCare formula claims to reverse issues in eyesight, and every ingredient is completely natural.

nolvadex estrogen blocker: tamoxifen pill – pct nolvadex

http://zithromaxbestprice.icu/# can i buy zithromax over the counter

zithromax capsules australia: zithromax prescription – order zithromax over the counter

https://lisinoprilbestprice.store/# zestoretic price

Thanks for your post. I have generally noticed that a majority of people are needing to lose weight simply because wish to appear slim along with attractive. Even so, they do not usually realize that there are many benefits for losing weight in addition. Doctors say that obese people are afflicted by a variety of conditions that can be instantly attributed to their excess weight. The good thing is that people who definitely are overweight as well as suffering from various diseases can help to eliminate the severity of their own illnesses by way of losing weight. You are able to see a constant but noted improvement with health while even a moderate amount of weight reduction is accomplished.

where can i get doxycycline: buy doxycycline 100mg – buy doxycycline cheap

what happens when you stop taking tamoxifen: tamoxifen cancer – tamoxifen effectiveness

http://zithromaxbestprice.icu/# zithromax price south africa

generic drug for lisinopril lisinopril 10mg online lisinopril 50 mg price

http://lisinoprilbestprice.store/# lisinopril 5 mg

lisinopril 40 mg mexico: how much is lisinopril 40 mg – lisinopril buy without prescription

lisinopril 12.5 mg 20 mg: lisinopril generic brand – zestoretic online

http://zithromaxbestprice.icu/# order zithromax over the counter

buy doxycycline online uk: order doxycycline online – buy doxycycline monohydrate

http://lisinoprilbestprice.store/# lisinopril pills 2.5 mg

can you buy zithromax over the counter in canada: where can you buy zithromax – zithromax online australia

buy zithromax no prescription: buy zithromax online – can i buy zithromax over the counter in canada

buy cytotec pills online cheap cytotec online buy cytotec online fast delivery

https://doxycyclinebestprice.pro/# doxycycline generic

http://cytotec.icu/# cytotec pills online

doxycycline mono: doxycycline 100mg – where can i get doxycycline

cytotec pills buy online: buy cytotec pills – buy misoprostol over the counter

http://nolvadex.fun/# tamoxifen rash

generic prinivil: 16 lisinopril – zestoretic coupon

zithromax coupon buy zithromax online buy zithromax 500mg online

zestril 20 mg price: lisinopril 15 mg tablets – lisinopril 4 mg

http://nolvadex.fun/# tamoxifen for gynecomastia reviews

http://mexicopharm.com/# mexico pharmacies prescription drugs mexicopharm.com

mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa: mexican pharmacy – medication from mexico pharmacy mexicopharm.com

best online pharmacies in mexico: mexico pharmacies prescription drugs – mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs mexicopharm.com

https://indiapharm.llc/# world pharmacy india indiapharm.llc

pet meds without vet prescription canada: Canada Drugs Direct – best online canadian pharmacy canadapharm.life

canadian discount pharmacy Canadian pharmacy best prices ed meds online canada canadapharm.life

mexican drugstore online: Best pharmacy in Mexico – mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs mexicopharm.com

certified canadian international pharmacy: Cheapest drug prices Canada – canadian online drugs canadapharm.life

reputable indian pharmacies: India pharmacy of the world – canadian pharmacy india indiapharm.llc

https://mexicopharm.com/# best online pharmacies in mexico mexicopharm.com

https://indiapharm.llc/# buy medicines online in india indiapharm.llc

mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs: mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs – mexican rx online mexicopharm.com

http://canadapharm.life/# canadian king pharmacy canadapharm.life

buy canadian drugs: Canadian online pharmacy – canadapharmacyonline legit canadapharm.life

reputable indian pharmacies Online medicine home delivery best india pharmacy indiapharm.llc

https://indiapharm.llc/# online shopping pharmacy india indiapharm.llc

canadian pharmacies online: Canadian online pharmacy – canadian pharmacy online canadapharm.life

mexican rx online: Medicines Mexico – best online pharmacies in mexico mexicopharm.com

escrow pharmacy canada: Canada pharmacy online – online canadian pharmacy reviews canadapharm.life

http://canadapharm.life/# canadian pharmacy ltd canadapharm.life

https://indiapharm.llc/# world pharmacy india indiapharm.llc

mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs: Mexico pharmacy online – buying from online mexican pharmacy mexicopharm.com

best canadian online pharmacy reviews: Canadian pharmacy best prices – canadian drug stores canadapharm.life

best india pharmacy: Medicines from India to USA online – best india pharmacy indiapharm.llc

http://canadapharm.life/# reputable canadian online pharmacies canadapharm.life

canadian drug pharmacy: Canada pharmacy online – canadian mail order pharmacy canadapharm.life

reputable indian pharmacies: world pharmacy india – best online pharmacy india indiapharm.llc

http://edpillsdelivery.pro/# ed meds

buy kamagra online usa: buy Kamagra – sildenafil oral jelly 100mg kamagra

https://sildenafildelivery.pro/# sildenafil 25

Sight Care is a daily supplement proven in clinical trials and conclusive science to improve vision by nourishing the body from within. The SightCare formula claims to reverse issues in eyesight, and every ingredient is completely natural.

GlucoTrust is a revolutionary blood sugar support solution that eliminates the underlying causes of type 2 diabetes and associated health risks. https://glucotrustbuynow.us/

Neotonics is an essential probiotic supplement that works to support the microbiome in the gut and also works as an anti-aging formula. The formula targets the cause of the aging of the skin. https://neotonicsbuynow.us/

natural remedies for ed: cheapest ed pills – best treatment for ed

http://levitradelivery.pro/# Buy Vardenafil 20mg online

Boostaro increases blood flow to the reproductive organs, leading to stronger and more vibrant erections. It provides a powerful boost that can make you feel like you’ve unlocked the secret to firm erections, youthful vigor, and satisfying sexual experiences. https://boostarobuynow.us/

Puravive introduced an innovative approach to weight loss and management that set it apart from other supplements. It enhances the production and storage of brown fat in the body, a stark contrast to the unhealthy white fat that contributes to obesity. https://puravivebuynow.us/

BioFit is an all-natural supplement that is known to enhance and balance good bacteria in the gut area. To lose weight, you need to have a balanced hormones and body processes. Many times, people struggle with weight loss because their gut health has issues. https://biofitbuynow.us/

Kamagra tablets cheap kamagra Kamagra 100mg

GlucoBerry is one of the biggest all-natural dietary and biggest scientific breakthrough formulas ever in the health industry today. This is all because of its amazing high-quality cutting-edge formula that helps treat high blood sugar levels very naturally and effectively. https://glucoberrybuynow.us/https://glucoberrybuynow.us/

With its all-natural ingredients and impressive results, Aizen Power supplement is quickly becoming a popular choice for anyone looking for an effective solution for improve sexual health with this revolutionary treatment. https://aizenpowerbuynow.us/

The Quietum Plus supplement promotes healthy ears, enables clearer hearing, and combats tinnitus by utilizing only the purest natural ingredients. Supplements are widely used for various reasons, including boosting energy, lowering blood pressure, and boosting metabolism. https://quietumplusbuynow.us/

Prostadine is a dietary supplement meticulously formulated to support prostate health, enhance bladder function, and promote overall urinary system well-being. Crafted from a blend of entirely natural ingredients, Prostadine draws upon a recent groundbreaking discovery by Harvard scientists. This discovery identified toxic minerals present in hard water as a key contributor to prostate issues. https://prostadinebuynow.us/

ed pills that really work: ed pills online – best otc ed pills

https://edpillsdelivery.pro/# treatment for ed

buy tadalafil from canada: Tadalafil 20mg price in Canada – cost of tadalafil generic

Kerassentials are natural skin care products with ingredients such as vitamins and plants that help support good health and prevent the appearance of aging skin. They’re also 100% natural and safe to use. The manufacturer states that the product has no negative side effects and is safe to take on a daily basis. Kerassentials is a convenient, easy-to-use formula. https://kerassentialsbuynow.us/

http://tadalafildelivery.pro/# where can i get tadalafil

http://levitradelivery.pro/# Levitra 10 mg best price

Java Burn is a proprietary blend of metabolism-boosting ingredients that work together to promote weight loss in your body.

usa over the counter sildenafil: sildenafil brand name india – 100mg sildenafil coupon

Boostaro increases blood flow to the reproductive organs, leading to stronger and more vibrant erections. It provides a powerful boost that can make you feel like you’ve unlocked the secret to firm erections https://boostarobuynow.us/

EyeFortin is a natural vision support formula crafted with a blend of plant-based compounds and essential minerals. It aims to enhance vision clarity, focus, and moisture balance. https://eyefortinbuynow.us/

Endo Pump Male Enhancement works by increasing blood flow to the penis, which assist to achieve and maintain erections. This formula includes nitric oxide, a powerful vasodilator that widens blood vessels and improves circulation. Other key ingredients https://endopumpbuynow.us/

GlucoBerry is one of the biggest all-natural dietary and biggest scientific breakthrough formulas ever in the health industry today. This is all because of its amazing high-quality cutting-edge formula that helps treat high blood sugar levels very naturally and effectively. https://glucoberrybuynow.us/

Dentitox Pro is a liquid dietary solution created as a serum to support healthy gums and teeth. Dentitox Pro formula is made in the best natural way with unique, powerful botanical ingredients that can support healthy teeth. https://dentitoxbuynow.us/

Gorilla Flow prostate is an all-natural dietary supplement for men which aims to decrease inflammation in the prostate to decrease common urinary tract issues such as frequent and night-time urination, leakage, or blocked urine stream. https://gorillaflowbuynow.us/

GlucoCare is a natural and safe supplement for blood sugar support and weight management. It fixes your metabolism and detoxifies your body. https://glucocarebuynow.us/

InchaGrow is a new natural formula that enhances your virility and allows you to have long-lasting male enhancement capabilities. https://inchagrowbuynow.us/

HoneyBurn is a revolutionary liquid weight loss formula that stands as the epitome of excellence in the industry. https://honeyburnbuynow.us/

Amiclear is a dietary supplement designed to support healthy blood sugar levels and assist with glucose metabolism. It contains eight proprietary blends of ingredients that have been clinically proven to be effective. https://amiclearbuynow.us/

Claritox Pro™ is a natural dietary supplement that is formulated to support brain health and promote a healthy balance system to prevent dizziness, risk injuries, and disability. This formulation is made using naturally sourced and effective ingredients that are mixed in the right way and in the right amounts to deliver effective results. https://claritoxprobuynow.us/

TropiSlim is the world’s first 100% natural solution to support healthy weight loss by using a blend of carefully selected ingredients. https://tropislimbuynow.us/

https://tadalafildelivery.pro/# tadalafil brand name in india

FlowForce Max is an innovative, natural and effective way to address your prostate problems, while addressing your energy, libido, and vitality. https://flowforcemaxbuynow.us/

Cortexi is a completely natural product that promotes healthy hearing, improves memory, and sharpens mental clarity. Cortexi hearing support formula is a combination of high-quality natural components that work together to offer you with a variety of health advantages, particularly for persons in their middle and late years. https://cortexibuynow.us/

Introducing TerraCalm, a soothing mask designed specifically for your toenails. Unlike serums and lotions that can be sticky and challenging to include in your daily routine, TerraCalm can be easily washed off after just a minute. https://terracalmbuynow.us/

buy generic tadalafil 20mg: cheap tadalafil canada – tadalafil tablets 20 mg buy

Serolean, a revolutionary weight loss supplement, zeroes in on serotonin—the key neurotransmitter governing mood, appetite, and fat storage. https://seroleanbuynow.us/

Alpha Tonic is a powder-based supplement that uses multiple natural herbs and essential vitamins and minerals to helpoptimize your body’s natural testosterone levels. https://alphatonicbuynow.us/

AquaPeace is an all-natural nutritional formula that uses a proprietary and potent blend of ingredients and nutrients to improve overall ear and hearing health and alleviate the symptoms of tinnitus. https://aquapeacebuynow.us/

Are you tired of looking in the mirror and noticing saggy skin? Is saggy skin making you feel like you are trapped in a losing battle against aging? Do you still long for the days when your complexion radiated youth and confidence? https://refirmancebuynow.us/

VidaCalm is an all-natural blend of herbs and plant extracts that treat tinnitus and help you live a peaceful life. https://vidacalmbuynow.us/

Neurozoom crafted in the United States, is a cognitive support formula designed to enhance memory retention and promote overall cognitive well-being. https://neurozoombuynow.us/

Gut Vita™ is a daily supplement that helps consumers to improve the balance in their gut microbiome, which supports the health of their immune system. It supports healthy digestion, even for consumers who have maintained an unhealthy diet for a long time. https://gutvitabuynow.us/

Researchers consider obesity a world crisis affecting over half a billion people worldwide. Vid Labs provides an effective solution that helps combat obesity and overweight without exercise or dieting. https://leanotoxbuynow.us/

Illuderma is a serum designed to deeply nourish, clear, and hydrate the skin. The goal of this solution began with dark spots, which were previously thought to be a natural symptom of ageing. The creators of Illuderma were certain that blue modern radiation is the source of dark spots after conducting extensive research. https://illudermabuynow.us/

Puralean incorporates blends of Mediterranean plant-based nutrients, specifically formulated to support healthy liver function. These blends aid in naturally detoxifying your body, promoting efficient fat burning and facilitating weight loss. https://puraleanbuynow.us/

BioVanish a weight management solution that’s transforming the approach to healthy living. In a world where weight loss often feels like an uphill battle, BioVanish offers a refreshing and effective alternative. This innovative supplement harnesses the power of natural ingredients to support optimal weight management. https://biovanishbuynow.us/

Abdomax is a nutritional supplement using an 8-second Nordic cleanse to eliminate gut issues, support gut health, and optimize pepsinogen levels. https://abdomaxbuynow.us/

Fast Lean Pro is a herbal supplement that tricks your brain into imagining that you’re fasting and helps you maintain a healthy weight no matter when or what you eat. It offers a novel approach to reducing fat accumulation and promoting long-term weight management. https://fastleanprobuynow.us/

Digestyl™ is natural, potent and effective mixture, in the form of a powerful pill that would detoxify the gut and rejuvenate the whole organism in order to properly digest and get rid of the Clostridium Perfringens. https://digestylbuynow.us/

Wild Stallion Pro, a natural male enhancement supplement, promises noticeable improvements in penis size and sexual performance within weeks. Crafted with a blend of carefully selected natural ingredients, it offers a holistic approach for a more satisfying and confident sexual experience. https://wildstallionprobuynow.us/

LeanBliss is a unique weight loss formula that promotes optimal weight and balanced blood sugar levels while curbing your appetite, detoxifying, and boosting your metabolism. https://leanblissbuynow.us/

Keratone addresses the real root cause of your toenail fungus in an extremely safe and natural way and nourishes your nails and skin so you can stay protected against infectious related diseases. https://keratonebuynow.us/

Protoflow is a prostate health supplement featuring a blend of plant extracts, vitamins, minerals, fruit extracts, and more. https://protoflowbuynow.us/

Folixine is a enhancement that regrows hair from the follicles by nourishing the scalp. It helps in strengthening hairs from roots. https://folixinebuynow.us/

sildenafil oral jelly 100mg kamagra cheap kamagra Kamagra 100mg price

LeanBiome is designed to support healthy weight loss. Formulated through the latest Ivy League research and backed by real-world results, it’s your partner on the path to a healthier you. https://leanbiomebuynow.us/

20 mg sildenafil cheap: cheap sildenafil – sildenafil in canada

otc ed pills: buy ed drugs online – cheapest ed pills

https://kamagradelivery.pro/# Kamagra tablets

http://sildenafildelivery.pro/# cheap sildenafil 50mg

п»їkamagra: Kamagra tablets – Kamagra Oral Jelly

http://edpillsdelivery.pro/# medicine for erectile

Levitra generic best price: п»їLevitra price – Vardenafil online prescription

minocycline 50 mg acne: stromectol guru – ivermectin cost australia

http://amoxil.guru/# amoxicillin order online

http://stromectol.guru/# buy ivermectin

paxlovid cost without insurance Buy Paxlovid privately paxlovid covid

http://paxlovid.guru/# paxlovid cost without insurance

http://paxlovid.guru/# paxlovid buy

paxlovid buy: buy paxlovid online – paxlovid pharmacy

https://paxlovid.guru/# п»їpaxlovid

paxlovid cost without insurance paxlovid best price paxlovid india

https://stromectol.guru/# ivermectin 6 mg tablets

https://clomid.auction/# buy generic clomid without insurance

http://prednisone.auction/# iv prednisone

buy prednisone canada: buy prednisone online canada – prednisone brand name india

https://prednisone.auction/# prednisone otc uk

http://amoxil.guru/# amoxicillin discount coupon

paxlovid pharmacy paxlovid price without insurance paxlovid price

https://prednisone.auction/# cost of prednisone

http://paxlovid.guru/# paxlovid covid

price of amoxicillin without insurance: Amoxicillin buy online – amoxicillin order online no prescription

When I originally commented I clicked the “Notify me when new comments are added” checkbox and now

each time a comment is added I get four emails with the same comment.

Is there any way you can remove me from that service?

Bless you!

https://clomid.auction/# where buy clomid without a prescription

Attractive section of content. I just stumbled upon your

blog and in accession capital to assert that

I get in fact enjoyed account your blog posts.

Anyway I’ll be subscribing to your feeds and even I achievement you access consistently

quickly.

https://prednisone.auction/# prednisone 10 mg over the counter

http://finasteride.men/# order generic propecia without insurance

lisinopril in mexico: over the counter lisinopril – lisinopril brand name canada

https://lisinopril.fun/# lisinopril 2.5 mg tablet

https://finasteride.men/# get cheap propecia without insurance

cost cheap propecia pill: Best place to buy propecia – buy propecia online

lasix generic lasix furosemide

https://finasteride.men/# propecia rx

price of lisinopril in india: buy lisinopril online – lisinopril prescription cost

furosemide 100mg: Buy Furosemide – lasix generic name

https://misoprostol.shop/# buy cytotec pills online cheap

http://furosemide.pro/# furosemide 40mg

zithromax capsules australia: how to buy zithromax online – zithromax online

https://lisinopril.fun/# lisinopril 200mg

buy cytotec in usa cheap cytotec buy cytotec online fast delivery

zithromax cost australia: buy zithromax z-pak online – zithromax prescription in canada

https://lisinopril.fun/# cost of lisinopril

http://misoprostol.shop/# Misoprostol 200 mg buy online

lasix furosemide 40 mg: Buy Lasix – furosemida 40 mg

cost of cheap propecia prices: Buy finasteride 1mg – generic propecia tablets

buy lasix online: Over The Counter Lasix – lasix generic name

https://misoprostol.shop/# buy cytotec online

where can you buy zithromax buy zithromax over the counter zithromax for sale cheap

https://finasteride.men/# buy cheap propecia no prescription

Abdomax is a nutritional supplement using an 8-second Nordic cleanse to eliminate gut issues, support gut health, and optimize pepsinogen levels. https://abdomaxbuynow.us/

cost of cheap propecia now: buy propecia – order cheap propecia no prescription

GlucoCare is a natural and safe supplement for blood sugar support and weight management. It fixes your metabolism and detoxifies your body. https://glucocarebuynow.us/

https://furosemide.pro/# lasix side effects

lasix generic: Buy Furosemide – lasix for sale

zithromax price south africa: Azithromycin 250 buy online – can i buy zithromax over the counter in canada

https://furosemide.pro/# furosemide

https://azithromycin.store/# zithromax online paypal

buy misoprostol over the counter Buy Abortion Pills Online cytotec pills buy online

buying cheap propecia without a prescription: Buy Finasteride 5mg – propecia cheap

Nervogen Pro is an effective dietary supplement designed to help patients with neuropathic pain. When you combine exotic herbs, spices, and other organic substances, your immune system will be strengthened. https://nervogenprobuynow.us/

DentaTonic is a breakthrough solution that would ultimately free you from the pain and humiliation of tooth decay, bleeding gums, and bad breath. It protects your teeth and gums from decay, cavities, and pain. https://dentatonicbuynow.us/

ProDentim is a nutritional dental health supplement that is formulated to reverse serious dental issues and to help maintain good dental health. https://prodentimbuynow.us/

Prostadine is a dietary supplement meticulously formulated to support prostate health, enhance bladder function, and promote overall urinary system well-being. Crafted from a blend of entirely natural ingredients, Prostadine draws upon a recent groundbreaking discovery by Harvard scientists. This discovery identified toxic minerals present in hard water as a key contributor to prostate issues. https://prostadinebuynow.us/

Reliver Pro is a dietary supplement formulated with a blend of natural ingredients aimed at supporting liver health

Sugar Defender is the #1 rated blood sugar formula with an advanced blend of 24 proven ingredients that support healthy glucose levels and natural weight loss. https://sugardefenderbuynow.us/

https://finasteride.men/# buying generic propecia without prescription

can you buy zithromax over the counter in australia: zithromax best price – buy zithromax online cheap

Neotonics is an essential probiotic supplement that works to support the microbiome in the gut and also works as an anti-aging formula. The formula targets the cause of the aging of the skin. https://neotonicsbuynow.us/

Red Boost is a male-specific natural dietary supplement. Nitric oxide is naturally increased by it, which enhances blood circulation all throughout the body. This may improve your general well-being. Red Boost is an excellent option if you’re trying to assist your circulatory system. https://redboostbuynow.us/

Fast Lean Pro is a herbal supplement that tricks your brain into imagining that you’re fasting and helps you maintain a healthy weight no matter when or what you eat. It offers a novel approach to reducing fat accumulation and promoting long-term weight management. https://fastleanprobuynow.us/

PowerBite is an innovative dental candy that promotes healthy teeth and gums. It’s a powerful formula that supports a strong and vibrant smile. https://powerbitebuynow.us/

Kerassentials are natural skin care products with ingredients such as vitamins and plants that help support good health and prevent the appearance of aging skin. They’re also 100% natural and safe to use. The manufacturer states that the product has no negative side effects and is safe to take on a daily basis. Kerassentials is a convenient, easy-to-use formula. https://kerassentialsbuynow.us/

https://zoracelbuynow.us/

zestril canada: buy lisinopril online – zestril cost price

lasix 100 mg: lasix online – lasix medication

https://finasteride.men/# buy propecia prices

lasix 40mg lasix 100 mg furosemida

https://misoprostol.shop/# cytotec pills buy online

how to order lisinopril online: High Blood Pressure – lisinopril 30mg coupon

https://finasteride.men/# buying propecia

top farmacia online: Farmacie a milano che vendono cialis senza ricetta – farmacia online piГ№ conveniente

п»їfarmacia online migliore Farmacie a milano che vendono cialis senza ricetta farmaci senza ricetta elenco

https://farmaciaitalia.store/# comprare farmaci online con ricetta

http://tadalafilitalia.pro/# farmaci senza ricetta elenco

http://avanafilitalia.online/# farmacie on line spedizione gratuita

farmacie online affidabili: avanafil generico – comprare farmaci online all’estero

http://farmaciaitalia.store/# farmacie online affidabili

farmacia online senza ricetta Tadalafil generico farmacia online piГ№ conveniente

migliori farmacie online 2023: kamagra gel prezzo – migliori farmacie online 2023

https://farmaciaitalia.store/# acquistare farmaci senza ricetta

https://farmaciaitalia.store/# farmacia online

farmacie on line spedizione gratuita: kamagra – acquisto farmaci con ricetta

https://kamagraitalia.shop/# farmacia online migliore

viagra naturale in farmacia senza ricetta: viagra online spedizione gratuita – viagra subito

comprare farmaci online all’estero acquistare farmaci senza ricetta acquisto farmaci con ricetta

https://tadalafilitalia.pro/# farmacia online senza ricetta

farmaci senza ricetta elenco: kamagra gel prezzo – migliori farmacie online 2023

http://avanafilitalia.online/# comprare farmaci online con ricetta

comprare farmaci online all’estero: kamagra gel – comprare farmaci online all’estero

http://kamagraitalia.shop/# farmacia online migliore

https://avanafilitalia.online/# farmacie online autorizzate elenco

farmaci senza ricetta elenco Tadalafil prezzo acquistare farmaci senza ricetta

cialis farmacia senza ricetta: viagra senza ricetta – viagra naturale

https://farmaciaitalia.store/# farmacie online sicure

I gave 1500mg cbd gummies a prove with a view the maiden adjust, and I’m amazed! They tasted distinguished and provided a sense of calmness and relaxation. My emphasis melted away, and I slept less ill too. These gummies are a game-changer since me, and I highly recommend them to anyone seeking natural stress alleviation and think twice sleep.

https://avanafilitalia.online/# migliori farmacie online 2023

top farmacia online: kamagra oral jelly consegna 24 ore – farmacie on line spedizione gratuita

buy prescription drugs from india: best online pharmacy india – buy prescription drugs from india

https://canadapharm.shop/# northwest canadian pharmacy

http://mexicanpharm.store/# mexico drug stores pharmacies

mexican mail order pharmacies: mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa – mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

indian pharmacy paypal: п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india – reputable indian pharmacies

https://indiapharm.life/# mail order pharmacy india

mexican pharmaceuticals online: mexico drug stores pharmacies – medication from mexico pharmacy

п»їbest mexican online pharmacies: mexico drug stores pharmacies – medication from mexico pharmacy

https://canadapharm.shop/# canada cloud pharmacy

buy prescription drugs from india indian pharmacies safe top 10 pharmacies in india

purple pharmacy mexico price list: mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs – mexico pharmacy

http://canadapharm.shop/# pharmacies in canada that ship to the us

reputable indian online pharmacy: online shopping pharmacy india – indian pharmacy paypal

https://mexicanpharm.store/# mexican mail order pharmacies

online pharmacy india: Online medicine home delivery – india online pharmacy

A big thank you for your blog.Really looking forward to read more.αλπηατω

https://indiapharm.life/# indianpharmacy com

п»їbest mexican online pharmacies: mexican rx online – mexican rx online

http://indiapharm.life/# top online pharmacy india

canadian discount pharmacy: canadian neighbor pharmacy – canadian pharmacy online

reputable indian online pharmacy: indian pharmacy online – pharmacy website india

http://indiapharm.life/# world pharmacy india

online pharmacy india: online shopping pharmacy india – pharmacy website india

canadian pharmacy scam: canadian pharmacy ltd – prescription drugs canada buy online

https://canadapharm.shop/# canada drugs online reviews

http://mexicanpharm.store/# buying prescription drugs in mexico

cheapest online pharmacy india: indian pharmacy – п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india

world pharmacy india: п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india – cheapest online pharmacy india