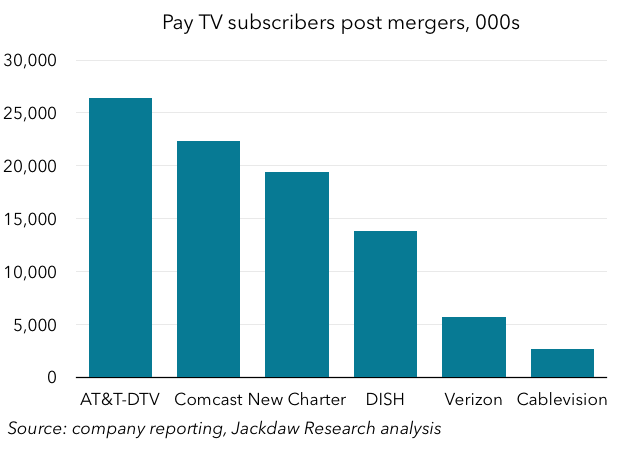

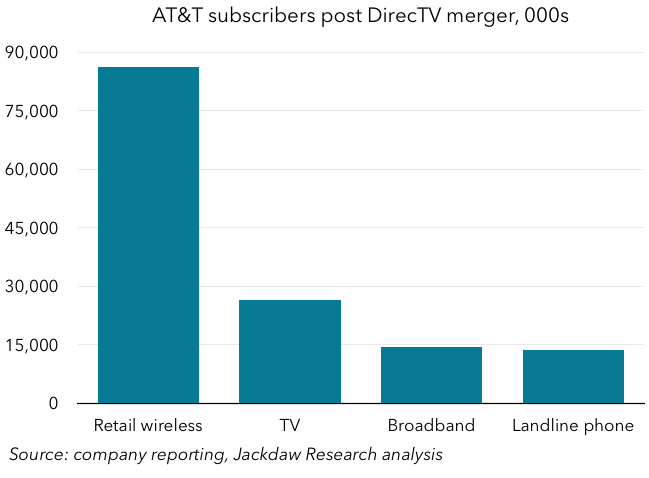

Last week, my weekly column was “TV’s Detour” and I focused on the first of what I described as two shifts that appeared to be happening in the world of television. The shift I discussed last week was the trend away from the television set and towards other devices, though I concluded that that might have been more of a detour than a lasting move, hence my title. This week, I wanted to pick up on the second of the shifts which is the move away from traditional Pay TV providers, with a view to evaluating to what extent this too might be a temporary detour rather than a permanent change.

Disruption embraced

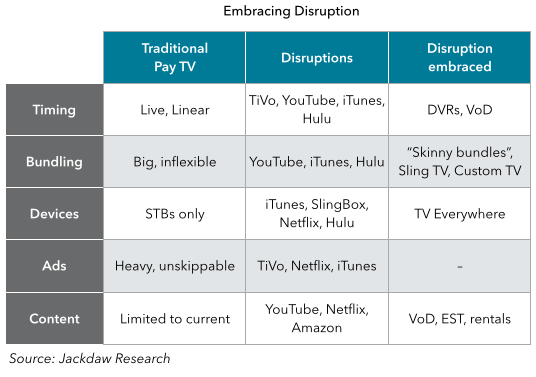

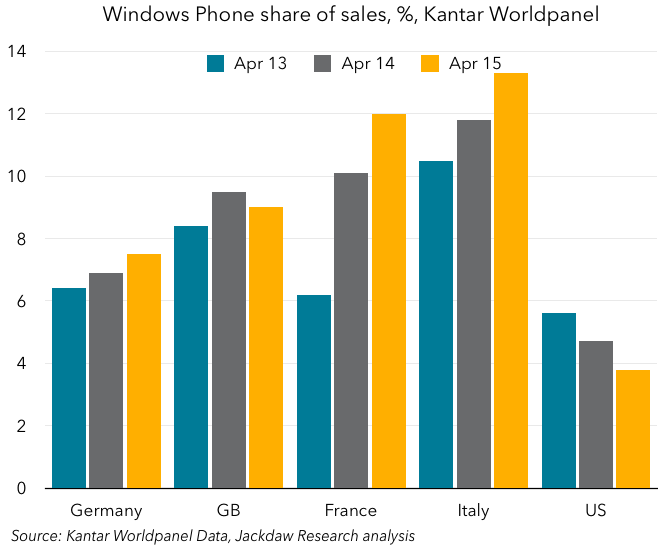

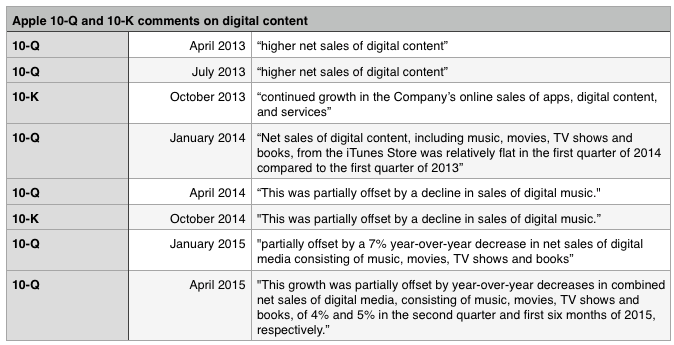

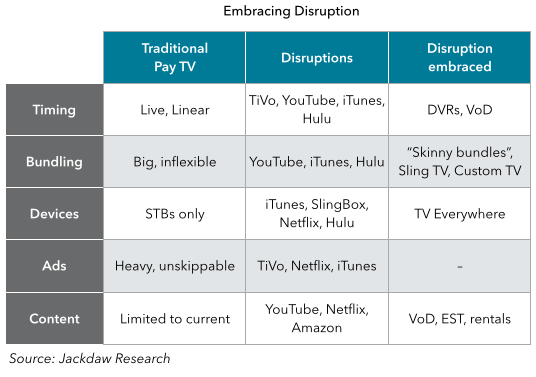

One of the fascinating things about pay TV providers has been that they have been slow to respond to disruption, but they have eventually responded to almost all the forms they’ve faced over time and ultimately embraced them, bringing the disruption in-house and somewhat neutralizing it in the process. The table below shows some examples:

The left column shows some of the key characteristics of traditional pay TV, almost all of which have been vulnerable to disruption because they don’t fit with the viewer’s ideal vision of TV. As I see it, nirvana for the viewer is to be able to watch the content they want, when they want, on the device they want, pay for only what they use, while seeing as few ads as possible. Pay TV providers have, over time, seen almost all these needs met first by others – whether by TiVo and other DVRs, which allowed users to time-shift content, or by Netflix and Hulu, which provide access on a variety of devices, or by a variety of on-demand services, allowing users to watch the content they want when they want. However, pay TV providers now offer both DVRs and on-demand services of their own, they offer “TV everywhere” solutions for watching content on devices other than the TV, and some are even partnering with players like Netflix to make their services available through the set-top box. Not all of these embraced disruptions are as good as the ones they’re responding to, but many of them are good enough to have allowed the pay TV providers to have brought the disruption in-house and neutralized the threat, at least to some extent.

However, there’s one cell in that right column that remains stubbornly empty and it’s the one that relates to advertising. Despite all that cable companies and others have done to respond to and embrace the other forms of disruption they’ve faced, this is the one that remains stubbornly unchanged (at least for the better) and the continued embrace by both pay TV companies and many of their content providers on advertising as an important revenue source shares some of the characteristics of addiction.

Defining addiction

As with any word, you can find a million definitions online if you spend enough time looking, but I found a handful that are useful in outlining the characteristics of addiction I believe the television industry is beginning to display with regard to advertising. Here are four (I’ve highlighted in bold text the parts that I think are particularly relevant):

From Psychology Today:

“Addiction is a condition that results when a person ingests a substance (e.g., alcohol, cocaine, nicotine) or engages in an activity (e.g., gambling, sex, shopping) that can be pleasurable but the continued use/act of which becomes compulsive and interferes with ordinary life responsibilities, such as work, relationships, or health. Users may not be aware that their behavior is out of control and causing problems for themselves and others.”

From Dictionary.com:

“the state of being enslaved to a habit or practice or to something that is psychologically or physically habit-forming, as narcotics, to such an extent that its cessation causes severe trauma.”

From Wikipedia:

“Addiction is a state characterized by compulsive engagement in rewarding stimuli, despite adverse consequences… The two properties that characterize all addictive stimuli are that they are reinforcing (i.e., they increase the likelihood that a person will seek repeated exposure to them) and intrinsically rewarding (i.e., something perceived as being positive or desirable).”

From ASAM (American Society of Addiction Medicine):

“Addiction is characterized by inability to consistently abstain, impairment in behavioral control, craving, diminished recognition of significant problems with one’s behaviors and interpersonal relationships, and a dysfunctional emotional response. Like other chronic diseases, addiction often involves cycles of relapse and remission. Without treatment or engagement in recovery activities, addiction is progressive and can result in disability or premature death.”

A progressive problem

The US television advertising addiction is certainly a progressive problem, as that ASAM definition suggests. The Wikipedia article on television advertising states that:

In the 1960s a typical hour-long American show would run for 51 minutes excluding advertisements. Today, a similar program would only be 42 minutes long; a typical 30-minute block of time now includes 22 minutes of programming and eight minutes of advertisements…

As a foreigner moving to the US about 11 years ago, I was struck, even then, by the sheer volume of television advertising. Even now, when I (very rarely watch) linear TV on the rare occasions when I flip through the channels in a hotel room, I find it’s almost impossible to figure out which program is playing on any given channel because so many of them seem to be playing ads. The ad load on US networks has been rising steadily and, as a result, live television content is becoming less and less watchable. Small wonder then so many of us seek to avoid it and have found various solutions for doing so. By sticking with the model though, TV content and service providers are “causing problems for themselves and others” (as per the Psychology Today definition) – including both their viewers and their advertisers.

Adverse consequences

One of the defining characteristics of addiction, per the Wikipedia definition, is the act or substance to which the user is addicted to has adverse consequences. That is the case with the TV industry’s ad addiction. The irony is the adverse consequences are moving in two opposite directions at the same time. First, the TV industry has, over time, become increasingly obsessed with certain relatively narrow demographics — because these attract the highest ad spend at the cost of neglecting other audiences (something I alluded to in an earlier piece). However, that very demographic advertisers are so keen to target (typically 18-49 male and but often the younger end of that) is the very group most likely to be using the various disruptive solutions which solve the ad problem. As such, TV providers are focusing on stuffing even more advertising into their programming rather than reducing it, which risks simply accelerating the move away from traditional platforms and services and onto those where tracking viewership is much tougher.

Withdrawal symptoms

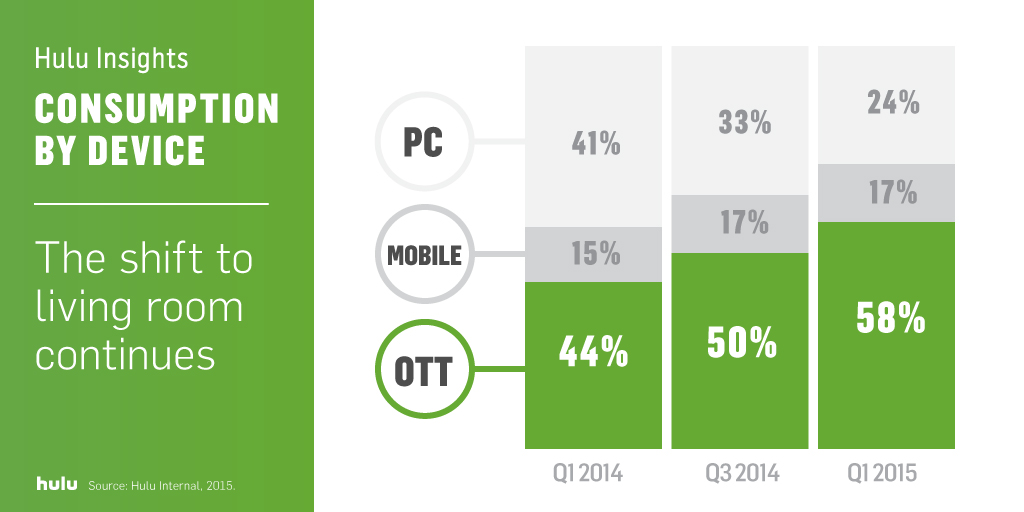

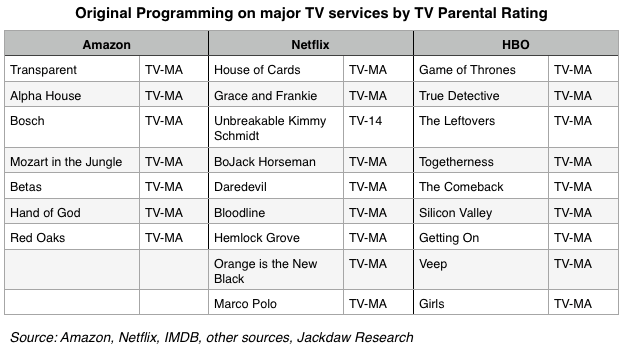

The big problem for the TV industry is advertising is an incredibly important source of revenue and, as such, it’s become habit forming, “to such an extent that its cessation causes severe trauma” to quote Dictionary.com. Simply moving away from advertising entirely over a short period of time seems implausible, given the high reliance on it for much of the industry. Affiliate and retransmission fees could have offered a potential way out for broadcast networks in particular as a potential replacement revenue source but instead, most companies seeing a rise in these fees have simply used them to pad their margins rather than start a transition away from ads, a move that makes perfect sense as part of a short term world view but much less sense over the long term. Meanwhile, HBO, Netflix, and others continue to demonstrate it’s perfectly possible to run a subscription video service with zero ad load very profitably, as long as the quality and quantity of the content available is sufficient. Hulu demonstrates that smaller ad loads are still more acceptable than those you’ll find in most live broadcasts and people will even pay, in some cases, to view this content instead.

A problem not unique to TV

Of course, TV is not the only industry heavily reliant on an ad-based business model – much of the Internet, relies heavily on it a well — but advertising entails compromises in any business. The content owners serve two masters and, as such, are at least as motivated to please advertisers as users, which can lead to privacy violations, feelings of creepiness as advertising becomes increasingly targeted (as it shortly will on TV and already is online), and increased ad load and ad-related technology foisted on consumers in the name of increasing revenue. The recent debate in Apple blogger circles about website advertising is symptomatic of this broader reliance on advertising as a business model.

However, TV has always made heavier use of advertising than almost any other media and advertising on TV has always been more invasive than in other media because it takes over the whole experience. If the second shift in television is to become a detour rather than a permanent change, all those involved in the traditional TV industry need to take a long look at the role of advertising, the (negative) role it plays, both in the customer experience and in the ecosystem itself, and determine how long they’re willing to put up with advertising in its current form. The risk, if they stick with it, is the one part of their model they’re unwilling to disrupt themselves becomes their undoing, as the eyeballs they so covet move to other platforms and services that don’t abuse them.