With the move to Windows 10, as disclosed in detail on January 21st, Microsoft is finally making clear its support of a unified system for devices from phones to an 84″ Surface Hub. Windows 10 is an interesting challenge that takes on the work of a considerable new approach to Windows–but it remains to be seen whether Microsoft will be as successful as Apple.

Apple and Windows, of course, have difference reports to markets. Apple, at the beginning of the iPhone era, had to make it successful in partnership with a Windows PC. Having gotten used to Windows with the iPod, Apple knew how to do it. And a number of those with Apple programs that made sense for mobiles, most notably Microsoft Office, had no choice but to support iOS versions (while some producers for iOS, such as Tweetbot, offered Windows and Mac versions).

Microsoft’s position is very different. Microsoft has millions of Windows PCs in use for every Windows Phone, while Apple must settle for a majority of iPhones and iPads not in use with Macs. Microsoft is determined to win a unified market of phones, tablets, and PCs. Its initial move is a new version of Office that will use a common code base for PCs and phones (we don’t know yet how Microsoft will handle Office for iPhone and iPad). In addition to Word, PowerPoint, and Excel, it is rewriting Outlook to handle mail and calendaring on mobile.

Can IT do it? I have no doubt a critical Microsoft goal is to make the Windows Phone an attractive choice to its corporate customer. Most IT departments support the use of the Phone as demanded by workers, especially top executives, but they don’t like it. Android is, in some ways, even worse, especially since Samsung’s effort to supply Knox, an enterprise security issue, has flopped. BlackBerry is still the darling of IT departments, but it’s not making a comeback. That creates an opportunity for Windows Phones.

The big challenge is software. Based on what they have shown, Microsoft has done an impressive job of coming up with a version of Office that runs on PCs, tablets (( The tablet does not really exist as a category in the Microsoft lineup. Devices with displays up to 6″ are phones. Bigger devices are PCs. The closest thing Microsoft has offered to a distinctive tablet, the Windows RT system, is dead. )), and phones.

The question is what about apps not provided by Microsoft? Windows has been fighting it out with BlackBerry for third place in the software market. The Windows Phone apps store remains mighty scarce territory. The most recent business-related apps, Dropbox, is certainly welcome, but extremely late to Windows Phone.

Easier than Apple. Microsoft’s pledge in the Windows 10 reveal is that code will run on all devices across the Windows range. The unified operating system is a valuable move; it may make things a bit easier than for developers of Apple products who need to work in OS X for PCs and iOS for iPhones and iPads (plus Windows for PCs). But it is still going to take a great deal of work to do versions of an app to work properly, and easily, in both PCs and phones. The Windows Phone segment has to get a lot bigger to make developers see it as worthwhile market. And if users are expected to use their Windows Phones for both business and personal purposes, building appeal will call for a lot of apps.

Despite the challenge facing Microsoft, this was a sound decision. The alternative was to get out of the phone business, struggle in the tablet segment, and be stuck in a PC business that shows little prospect for growth. From Windows Phones to HoloLens and the Surface Hub, Satya Nadella is determined to rebuild Microsoft, and there’s no chance of winning without taking on some serious risks.

Despite the challenge facing Microsoft, this was a sound decision. The alternative was to get out of the phone business, struggle in the tablet segment, and be stuck in a PC business that shows little prospect for growth. From Windows Phones to HoloLens and the Surface Hub, Satya Nadella is determined to rebuild Microsoft, and there’s no chance of winning without taking on some serious risks.

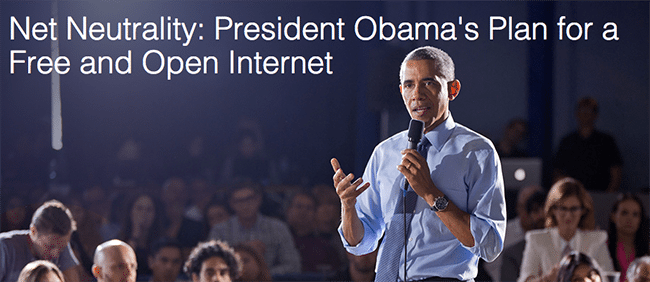

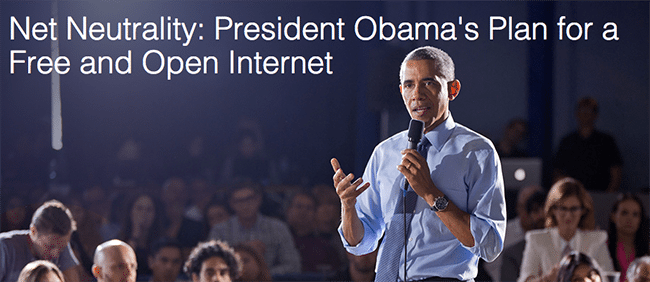

Most governments’ reaction to the terrorist attack on Charlie Hebdo and a kosher market in Paris seemed sensible. The major exception was a pledge by Prime Minister David Cameron to shut down encryption on messages in the U.K. No better is the push on President Obama to follow the mission. One reason for limited reaction in the U.S. is the lack of memory of the last U.S. fight in the 1990s.

Most governments’ reaction to the terrorist attack on Charlie Hebdo and a kosher market in Paris seemed sensible. The major exception was a pledge by Prime Minister David Cameron to shut down encryption on messages in the U.K. No better is the push on President Obama to follow the mission. One reason for limited reaction in the U.S. is the lack of memory of the last U.S. fight in the 1990s. The National Security Agency came up with a scheme called Skipjack, better remembered by its implementation on a chip called Clipper (left). The program would have made available two encryption codes — the regular code for users and an encrypted “escrow” code available to law enforcement. The Clinton administration fiercely supported the plan, with the effort led by Vice President Al Gore (although the effort got started under President George H.W. Bush, it really got rolling under Bill Clinton). The proposal set off a spirited argument between the technology industry and privacy and secrecy advocates on one side and the Clinton Administration, the NSA, and the FBI on the other.

The National Security Agency came up with a scheme called Skipjack, better remembered by its implementation on a chip called Clipper (left). The program would have made available two encryption codes — the regular code for users and an encrypted “escrow” code available to law enforcement. The Clinton administration fiercely supported the plan, with the effort led by Vice President Al Gore (although the effort got started under President George H.W. Bush, it really got rolling under Bill Clinton). The proposal set off a spirited argument between the technology industry and privacy and secrecy advocates on one side and the Clinton Administration, the NSA, and the FBI on the other.

Ed Colligan, a founder and former CEO of Palm, got it right. In a post to

Ed Colligan, a founder and former CEO of Palm, got it right. In a post to

If I were looking for people to break down the force of TV show producers (including sports), broadcasters, and cable carriers, I’d keep a close eye on Charlie Ergen, founder and chairman of DISH Network.

If I were looking for people to break down the force of TV show producers (including sports), broadcasters, and cable carriers, I’d keep a close eye on Charlie Ergen, founder and chairman of DISH Network.

A few months ago, as I was slowly recovering from illness, I assumed I would be unable to go to CES. The recovery came, but I found it hard to change my mind. My official excuse was CES would be exhausting, and it would. But it is looking like there will be a distinct shortage of news in Las Vegas next week. While CES still has reason for others, from meeting with manufacturers and vendors to seeing hundreds of obscure Chinese products, I’m still looking for news.

A few months ago, as I was slowly recovering from illness, I assumed I would be unable to go to CES. The recovery came, but I found it hard to change my mind. My official excuse was CES would be exhausting, and it would. But it is looking like there will be a distinct shortage of news in Las Vegas next week. While CES still has reason for others, from meeting with manufacturers and vendors to seeing hundreds of obscure Chinese products, I’m still looking for news.

Jean-Louis Gassée, a veteran executive, investor, and observer of the tech industry, wrote an

Jean-Louis Gassée, a veteran executive, investor, and observer of the tech industry, wrote an

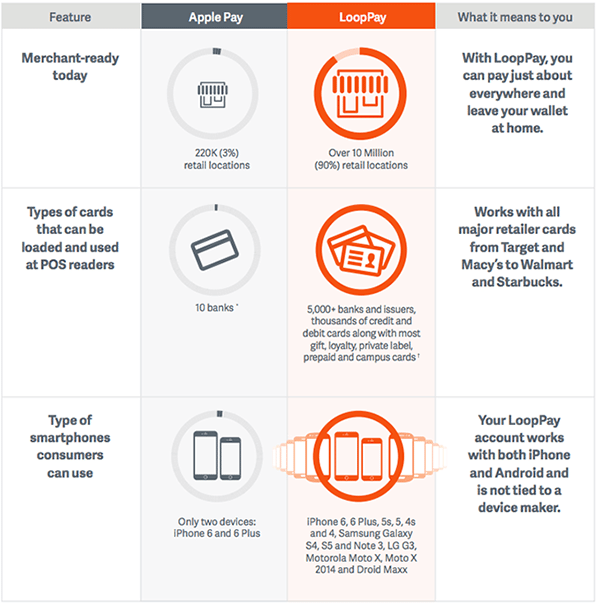

It looks like Samsung would face a serious hurdle with LoopPay in challenging both Apple Pay and CurrentC. Apple and its supporters are moving aggressively to take advantage of the solo control of credit card transactions. The other night, I saw back to back TV ads from CitiBank and BankAmerica supporting Apple Pay. MCX supporters Target and Walmart are likely to advertise CurrentC when it becomes available on phones next year.

It looks like Samsung would face a serious hurdle with LoopPay in challenging both Apple Pay and CurrentC. Apple and its supporters are moving aggressively to take advantage of the solo control of credit card transactions. The other night, I saw back to back TV ads from CitiBank and BankAmerica supporting Apple Pay. MCX supporters Target and Walmart are likely to advertise CurrentC when it becomes available on phones next year.

In PCs, Lenovo has had somewhat slow but steady growth in the computer market, having taken the number one spot over Hewlett-Packard this year. It’s my bias, but I find ThinkPads the only serious contenders to MacBooks. Lenovo also does well with ThinkCentre desktops, a corporate market to which most industry analysts don’t give a lot of attention. Consumers and small business markets are offered Lenovo-branded laptops and desktops. And the redone Lenovo Yoga may be the best Windows table available.

In PCs, Lenovo has had somewhat slow but steady growth in the computer market, having taken the number one spot over Hewlett-Packard this year. It’s my bias, but I find ThinkPads the only serious contenders to MacBooks. Lenovo also does well with ThinkCentre desktops, a corporate market to which most industry analysts don’t give a lot of attention. Consumers and small business markets are offered Lenovo-branded laptops and desktops. And the redone Lenovo Yoga may be the best Windows table available.

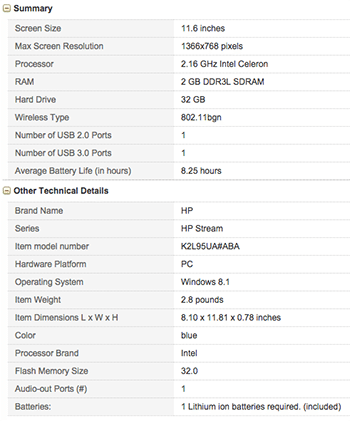

HP’s current PC competition is a tough business. The new Stream line of Windows notebooks is designed as a low-end offering and looks to be pretty well suited for customers who can get by fine with minimal service–when you realize minimal service includes a 1366×768 display, a 2.16 GHz processor and a 8.25 hour battery. The 11.6″ display (stats on the left) costs just $200, while a 13″ display costs $225. The laptop even includes a one-year subscription to Microsoft Office Personal with 1 TB of storage on Microsoft OneDrive cloud storage.

HP’s current PC competition is a tough business. The new Stream line of Windows notebooks is designed as a low-end offering and looks to be pretty well suited for customers who can get by fine with minimal service–when you realize minimal service includes a 1366×768 display, a 2.16 GHz processor and a 8.25 hour battery. The 11.6″ display (stats on the left) costs just $200, while a 13″ display costs $225. The laptop even includes a one-year subscription to Microsoft Office Personal with 1 TB of storage on Microsoft OneDrive cloud storage.