This week’s Techpinions podcast features Ben Bajarin and Bob O’Donnell discussing the debut of Qualcomm’s Snapdragon 888 chip and its potential impact on the premium smartphone market, analyzing the news on custom chips, new computing instances and new hybrid cloud options from Amazon’s AWS Cloud computing division, and chatting about the debut of Google’s Android Enterprise Essentials for simply and securely managing fleets of business-owned Android phones.

Category: Google

Podcast: AMD Earnings, Congressional Hearings, Amazon, Apple, Facebook and Google Earnings

This week’s Techpinions podcast features Ben Bajarin and Bob O’Donnell analyzing the quarterly financial results from AMD and what they say about the semiconductor industry overall, discussing the congressional anti-trust hearings with major tech CEOs, and chatting about the earnings from those same companies as well.

Podcast: Google Cloud Next, G Suite, IT Priority Study, Twitter Hack

This week’s Techpinions podcast features Carolina Milanesi and Bob O’Donnell analyzing the announcements from Google’s Cloud Next event, including new offerings for GCP and G Suite, discussing a new study on IT prioritization changes from the pandemic, and chatting on the big Twitter hack.

New Workplace Realities Highlight Opportunity for Cloud-Based Apps and Devices

One of the numerous interesting outcomes of our new work realities is that many tech-related ideas introduced over the past few years are getting a fresh look. In particular, products and services based on concepts that seemed sound in theory but ran into what I’ll call “negative inertia”—that is, a huge, seemingly immovable installed base of a legacy technology or application—are being reconsidered.

Some of the most obvious examples of these are cloud-based applications. While there’s certainly been strong adoption of consumer-based cloud services, such as Netflix, Spotify, and many others, the story hasn’t been quite as clear-cut in the business side of the world. Most organizations and institutions (including schools) still use a very large number of pre-packaged or legacy custom-built applications that haven’t been moved to the cloud.

For understandable reasons, that situation has started to change, and the percentage of cloud-friendly or cloud-native applications has begun to increase. Although the numbers aren’t going to change overnight (or even in the next few months), it’s fairly clear now to even the most conservative of IT organizations that the time to expand their usage of cloud-based software and computing models is now.

As a result of this shift in mindset, businesses are reconsidering their interest in and ability to use even more cloud-friendly tools. This, in turn, is starting to create a bit of a domino effect where previous dependencies and/or barriers that were previously considered insurmountable are now being tossed aside at the drop of a hat. It’s truly a time for fresh thinking in IT.

At the same time, companies also now have the benefit of learning from others that may have made more aggressive moves to the cloud several years back. In addition, they recognize that they can’t just start over, but need to use the existing hardware and software resources that they currently own or have access to. The end result is a healthy, pragmatic focus on finding tools that can help companies meet their essential needs more effectively. In real-world terms, that’s translating to a growing interest in hybrid cloud computing models, where both elements of the public cloud and on-premise or managed computing resources in a private cloud come together to create an optimal mix of capabilities for most organizations.

It’s also allowing companies to take a fresh look at alternatives to tools that may have been a critical part of their organization for a long time. In the case of office productivity suites, for example, companies that have relied on the traditional, licensed versions of Microsoft Office can start to more seriously consider something like Google’s cloud native G Suite as they make more of a shift to the cloud. Of course, they may also simply choose to switch to the newly updated Microsoft 365 cloud-based versions of their productivity suite. Either way, moving to cloud-based office productivity apps can go a long way towards a more flexible IT organization, as well as getting end users more accustomed to accessing all their critical applications from the web.

Directly related to this is the ability to look at new alternatives for client computing devices. As I’ve discussed previously, PC clamshell-based notebook form factors have become the de facto workhorses for most remote workers now and the range of different laptop needs has grown with the number of people now using them. The majority of those devices have been (and will continue to be) Windows-based, but as companies start to rely more on cloud-based applications across the board, Chromebooks become a viable option for more businesses as well.

Most of the attention (and sales) for Chromebooks to date has been in the education market—where they’ve recently proven to be very useful for learn-at-home applications—but the rapidly evolving business app ecosystem does start to shift that story. It also doesn’t hurt that the big PC vendors (Dell, HP, and Lenovo) all have a line of business-focused Chromebooks. On top of that, we’re starting to see some interesting innovations in Chromebook form factors, with options ranging from basic clamshells to convertible 2-in-1s.

The bottom line is that as companies continue to adapt their IT infrastructure to support our new workplace realities, there are a number of very interesting potential second-order effects that may result from quickly adapting to a more cloud-focused world.. While we aren’t likely to move to the kind of completely cloud-dependent vision that used to be posited as the future of computing, it’s clear that we are on the brink of what will undoubtedly be some profound changes in how, and with what tools, we all work.

Podcast: Tech Earnings from Facebook, Alphabet/Google, Microsoft, Amazon, Apple

This week’s Techpinions podcast features Carolina Milanesi and Bob O’Donnell analyzing this week’s big tech quarterly earnings reports from Facebook, Google’s parent company Alphabet, Microsoft, Amazon and Apple, with a focus on what the numbers mean for each of the companies individually and for the tech industry as a whole.

Google Anthos Extending Cloud Reach with Cisco, Amazon and Microsoft Connections

While it always sounds nice to talk about complete solutions that a single company can offer, in today’s reality of multi-vendor IT environments, it’s often better if everyone can play together. The strategy team over at Google Cloud seems to be particularly conscious of this principle lately and are working to extend the reach of GCP and their Anthos platform into more places.

Last week, Google made several announcements, including a partnership with Cisco that will better connect Cisco’s software-defined wide area network (SD-WAN) tools with Google Cloud. Google also announced the production release of Anthos for Amazon’s AWS and a preview release of Anthos for Microsoft’s Azure cloud. These two new Anthos tools are applications/services for both migrating and managing cloud workloads to and from GCP to AWS or Azure respectively.

The Cisco-Google partnership offering is officially called the Cisco SD-WAN Hub with Google Cloud. It provides a manageable private connection for applications all the way from an enterprise’s data center to the cloud. Many organizations use SD-WAN tools to manage the connections between branches of an office or other intra-company networks, but the new tools extend that reach to Google’s GCP cloud platform. What this means is that companies can see, manage, and measure the applications they share over SD-WAN connections from within their organizations all the way out to the cloud.

Specifically, the new connection fabric being put into place with this service (which is expected to be previewed at the end of this year) will allow companies to do things like maintain service-level agreements, compliance policies, security settings, and more for applications that reach into the cloud. Without this type of connectivity, companies have been limited to maintaining these services only for internal applications. In addition, the Cisco-powered connection gives companies the flexibility to put portions of an application in one location (for example, running AI/ML algorithms in the cloud), while running another portion, such as the business logic, on a private cloud, but managing them all through Google’s Anthos.

Given the growing interest and usage of hybrid cloud computing principles—where applications can be run both within local private clouds and in public cloud environments—these connection and management capabilities are critically important. In fact, according to the TECHnalysis Research Hybrid and Multi-Cloud study, roughly 86% of organizations that have any type of cloud computing efforts are running private clouds, and 83% are running hybrid clouds, highlighting the widespread use of these computing models and the strategically important need for this extended reach.

Of course, in addition to hybrid cloud, there’s been a tremendous increase in both interest and usage of multi-cloud computing, where companies leverage more than one different cloud provider. In fact, according to the same study, 99% of organizations that leverage cloud computing use more than one public cloud provider. Appropriately enough, the other Anthos announcements from Google were focused on the ability to potentially migrate and to manage cloud-based applications across multiple providers. Specifically, the company’s Anthos for AWS allows companies to move existing workloads from Amazon’s Web Services to GCP (or the other way, if they prefer). Later this year, the production version of Anthos for Azure will bring the same capabilities to and from Microsoft’s cloud platform.

While the theoretical concept of moving workloads back and forth across providers, based on things like pricing or capability changes, sounds interesting, realistically speaking, even Google doesn’t expect workload migration to be the primary focus of Anthos. Instead, just having the potential to make the move gives companies the ability to avoid getting locked into a single cloud provider.

More importantly, Anthos is designed to provide a single, consistent management backplane to an organization’s cloud workloads, allowing them all to be managed from a single location—eventually, regardless of the public cloud platform on which they’re running. In addition, like many other vendors, Google incorporates a number of technologies into Anthos that lets companies modernize their applications. The ability to move applications running inside virtual machines into containers, for example, and then to leverage the Kubernetes-based container management technologies that Anthos is based on, for example, is something that a number of organizations have been investigating.

Ultimately, all of these efforts appear to be focused on making hybrid, multi-cloud computing efforts more readily accessible and more easily manageable for companies of all sizes. Industry discussions on these issues have been ongoing for years now, but efforts like these emphasize that they’re finally becoming real and that it takes the efforts of multiple vendors (or tools that work across multiple platforms) to make them happen.

Podcast: Apple Google Contact Tracing, iPhone SE, OnePlus 8, Samsung 10 Lite

This week’s Techpinions podcast features Carolina Milanesi and Bob O’Donnell analyzing the surprising announcement from Apple and Google to work together on creating a smartphone-based system for tracking those who have been exposed to people with COVID-19, and discussing the launch of several new moderately priced smartphones and what they mean to the overall smartphone market.

Apple Google Contact Tracing Effort Raises Fascinating New Questions

In a move that caught many off guard—in part because of its release on the notoriously slow news day of Good Friday—Apple and Google announced an effort to create a standardized means of sharing information about the spread of the COVID-19 virus. Utilizing the Bluetooth Low Energy (LE) technology that’s been built into smartphones for the last 6 or 7 years and some clever mechanisms for anonymizing the data, the companies are working on building a standard API (application programming interface) that can be used to inform people if they’ve come into contact with someone who’s tested positive for the virus.

Initially those efforts will require people to download and enable specialized applications from known health care providers, but eventually the two companies plan to embed this capability directly into their respective mobile phone operating systems: iOS and Android.

Numerous articles have already been written about some of the technical details of how it works, and the companies themselves have put together a relatively simple explanation of the process. Rather than focusing on those details, however, I’ve been thinking more about the second-order impacts from such a move and what they have to say about the state of technology in our lives.

First, it’s amazing to think how far-reaching and impactful an effort like this could prove to be. While it may be somewhat obvious on one hand, it’s also easy to forget how widespread and common these technologies have become. In an era when it’s often difficult to get coordinated efforts within a single country (or even state), with one decisive step, these two tech industry titans are working to put together a potential solution that could work for most of the world. (Roughly half the world’s population owns a smartphone that runs one of these OS’s and a large percentage of people who don’t have one likely live with others who do. That’s incredible.)

With a few notable exceptions, tech industry developments essentially ignore country boundaries and have become global in nature right before our eyes. At times like this, that’s a profoundly powerful position to be in—and a strong reason to hope that, despite potential difficulties, the effort is a success. Of course, because of that reach and power, it also wouldn’t be terribly surprising to see some governments raise concerns about these advancements as they are further developed and as the potential extent of their influence becomes more apparent. Ultimately, however, while there has been discussion in the past of the potential good that technology can bring to the world, this combined effort could prove to be an actual life and death example of that good.

Unfortunately, some of the concerns regarding security, privacy, and control that have been raised about this new effort also highlight one of the starkest examples of what the potential misuse of widespread technology could do. And this is where some of the biggest questions about this project are centered. Even people who understand that the best of intentions are at play also know that concerns about data manipulation, creating false hopes (or fears), and much more are certainly valid when you start talking about putting so many people’s lives and personal health data under this level of technical control and scrutiny.

While there are no easy answers to these types of questions, one positive outcome that I certainly hope to see as a result of this effort is enhanced scrutiny of any kind of personal tracking technologies, particularly those focused on location tracking. Many of these location-based or application-driven efforts to harvest data on what we’re doing, what we’re reading, where we’re going, and so on—most all of which are done for the absurdly unimportant task of “personalizing” advertisements—have already gotten way out of hand. In fact, it felt like many of these technologies were just starting to see some real push back as the pandemic hit.

Let’s hope that as more people get smarter about the type of tracking efforts that really do matter and can potentially impact people’s lives in a positive way, we’ll see much more scrutiny of these other unimportant tracking efforts. In fact, with any luck there will be much more concentrated efforts to roll back or, even better, completely ban these hidden, little understood and yet incredibly invasive technologies and the mountains of data they create. As it is, they have existed for far too long. The more light that can be shone into these darker sides of technology abuse, the more outrage it will undoubtedly cause, which should ultimately force change.

Finally, on a very different note, I am quite curious to see how this combined Apple Google effort could end up impacting the overall view of Google. While Apple is generally seen to be a trustworthy company, many people still harbor concerns around trusting Google because of some of the data collection policies (as well as ad targeting efforts) that the company has utilized in the past. If Google handles these efforts well—and uses the opportunity to become more forthright about its other data handling endeavors—I believe they could gain a great deal of trust back from many consumers. They’ve certainly started making efforts in that regard, so I hope they can use this experience to do even more.

Of course, if the overall efficacy of this joint effort doesn’t prove to be as useful or beneficial as the theory of it certainly sounds—and numerous concerns are already being raised—none of these second-order impacts will matter much. I am hopeful, however, that progress can be made, not only for the ongoing process of managing people’s health and information regarding the COVID-19 pandemic, but for how technology can be smartly leveraged in powerful and far-reaching ways.

Podcast: Made by Google Event, Poly and Zoomtopia, Sony 360 Reality Audio

This week’s Tech.pinions podcast features Carolina Milanesi and Bob O’Donnell analyzing the announcements from the Made by Google hardware launch event, including the Pixel 4 smartphone, discussing new videoconferencing hardware from Poly and collaboration tools from Zoom’s Zoomtopia conference, and chatting about Sony’s new multichannel audio format release.

Next Major Step in AI: On-Device Google Assistant

The ability to have a smartphone respond to things you say has captivated people since the first demos of Siri on an iPhone over 7 years ago. Even the thought of an intelligent response to a spoken request was so science fiction-like that people were willing to forgive some pretty high levels of inaccuracy—at least for a little while.

Thankfully, things progressed on the voice-based computing and personal assistant front with the successful launch of Amazon’s Alexa-powered Echo smart speakers, and the Google Assistant found on Android devices, as well as Google (now Nest) Home smart speakers. All of a sudden, devices were accurately responding to our simple commands and providing us with an entirely new way of interacting with both our devices and the vast troves of information available on the web.

The accuracy of those improved digital assistants came with a hidden cost, however, as the recent revelations of recordings made by Amazon Alexa-based devices has laid bare. Our personal information, or even complete conversations from within the privacy of our homes, were being uploaded to the cloud for other systems, or even people, to analyze, interpret, and respond to. Essentially, the computing power and AI intelligence necessary to respond to our requests or properly interpret what we meant required the enormous computing resources of cloud-based data centers, full of powerful servers, running large, complicated neural network models.

Different companies used different resources for different reasons, but regardless, in order to get access to the power of voice-based digital assistants, you had to be willing to give up some degree of privacy, no matter which one you used. It was a classic trade-off of convenience versus confidentiality. Until now.

As Google demonstrated at their recent I/O developer conference, they now have the ability to run the Google Assistant almost entirely on the smartphone itself. The implications of this are enormous, not just from a privacy perspective (although that’s certainly huge), but from a performance and responsiveness angle as well. While connections to LTE networks and the cloud are certainly fast, they can’t compete with local computing resources. As a result, Google reported up to a 10x gain in responsiveness to spoken commands.

In the real-world that not only translates to faster answers, but a significantly more intuitive means of interacting with the assistant that more closely mimics what its like to speak with another human being. Plus, the ability to run natural language recognition models locally on the smartphones opens up the possibility for longer multi-part conversations. Instead of consisting of awkward silences and stilted responses, as they typically do now, these multi-turn conversations can now take on a more natural, real-time flow. While this may sound subtle, the difference in real-world experience literally shifts from something you have to endure to something you enjoy doing, and that can translate to significant increases in usage and improvements in overall engagement.

In addition, as hinted at earlier, the impact on privacy can be profound. Instead of having to upload your verbal input to the cloud, it can be analyzed, interpreted, and reacted to on the device, keeping your personal data private, as it should be. As Google pointed out, they are using a technique called federated learning that takes some of your data and sends it to the cloud in an anonymized form in order to be combined with others’ data and improve the accuracy of its models. Once those models are improved, they can then be sent back down to the local device, so that the overall accuracy and effectiveness of the on-device AI will improve over time.

Given what a huge improvement this is to cloud-based assistants, it’s more than reasonable to wonder why it didn’t get done before. The main reason is that the algorithms and datasets necessary to run this work used to be enormous and could only run with the large amounts of computing infrastructure available in the cloud. In addition, in order to create its models in the first place, Google needed a large body of data to build models that can accurately respond to people’s requests. Recently, however, Google has been able to shrink its models down to a size that can run comfortably even on lower-end Android devices with relatively limited storage.

On the smartphone hardware side, not only have we seen the continued Moore’s law-driven increases in computing power that we’ve enjoyed on computing devices for nearly 50 years, but companies like Qualcomm have brought AI-specific accelerator hardware into a larger body of mainstream smartphones. Inside most of the company’s Snapdragon series of chips is the little-known Hexagon DSP (digital signal processor), a component that is ideally suited to run the kinds of AI-based models necessary to enable on-device voice assistants (as well as computational photography and other cool computer vision-based applications). Qualcomm has worked alongside Google to develop a number of software hooks to neural networks they call the AndroidNN API that allows these to run faster and with more power efficiency on devices that include the necessary hardware. (To be clear, AI algorithms can and do run on other hardware inside smartphones—including both the CPU and GPU—but they can run more efficiently on devices that have the extra hardware capabilities.)

The net-net of all these developments is a decidedly large step forward in consumer-facing AI. In fact, Google is calling this Assistant 2.0 and is expected to make it available this fall with the release of the upcoming Q version of Android. It will incorporate not just the voice-based enhancements, but computer vision AI applications, via the smartphone camera and Google Lens, that can be done on device as well.

Even with these important advances, many people may view this next generation assistant as a more subtle improvement than the technologies might suggest. The reality is that many of the steps necessary to take us from the frustrating, early days of voice-based digital assistants, to the truly useful, contextually intelligent helpers that we’re all still hoping for are going to be difficult to notice on their own, or even in simple combinations. Achieving the science fiction-style interactions that the first voice-based command tools seemed to imply is going to be a long, difficult path. As with the growth of children, the day-to-day changes are easy to miss, but after a few years, the advancements are, and will be, unmistakable.

Podcast: Microsoft Build 2019, Google I/O 2019

This week’s Tech.pinions podcast features Carolina Milanesi and Bob O’Donnell analyzing the announcements from the big developer conferences hosted by Microsoft and Google, including advancements in smart assistants, browser privacy, and more.

If you happen to use a podcast aggregator or want to add it to iTunes manually the feed to our podcast is: techpinions.com/feed/podcast

Samsung Galaxy Fold Unfolds the Future

I have seen the future. I have touched the future. I’ve experienced the future. And I love it.

How you ask? I’m one of the lucky few who has gotten to play for a few hours with the world’s first commercially available foldable phone, the Samsung Galaxy Fold (set for official release on April 26), and it’s amazing. The experience of looking at the normal-sized 4.6” front display on the device, and then unfolding it to unveil the same app in much larger form on the beautiful 7.3” screen is something I don’t think I will get tired of for some time.

But, it’s not perfect. First, at a price of nearly $2,000, it’s clearly not for everyone. This is the Porsche of smartphones, and not everyone can or will want to pay that much for a phone. Second, yes, at certain angles or in certain light, you can notice a crease in the middle of the large display when the phone is unfolded. In real-world use, however, I found that it completely disappears—it didn’t bother me in the least. Finally, yes, it is a bit chunky, especially compared to the sleek, single-screen devices to which many of us have become accustomed. However, it’s not uncomfortable to hold, and most importantly, it will still easily fit into a pants pocket (or nearly anywhere else you store your existing smartphone).

More importantly, the Galaxy Fold completely transforms how we can, and should, think about smartphones. Open up the phone and you’ll immediately recognize that this is an always-connected computer that you can carry in your pocket. Practically speaking, it lets you do all the digital activities we’ve grown attached to in an easier, faster, and profoundly more satisfying way.

Want to watch TV shows or movies on the go? You can’t get a better or more compelling mobile experience right now than what you’ll see on the Galaxy Fold. Looking for directions? Start your map search on the front screen of the device, then unfold it to display the entire area around your destination. It’s a revelation. Want to web surf, and chat, and check out social media at the same time? The Fold’s ability to simultaneously show three different applications in reasonably-sized windows—a feature Samsung calls Multi-Active Windows—matches the kind of experience that has required a large tablet or PC in the past.

I could go on, but I think you get the idea. The Galaxy Fold radically changes how we’re going to think about and use mobile devices, and frankly, makes most of our existing phones look a bit—no, a lot—old-fashioned. I realize it may sound somewhat hyperbolic, but I honestly haven’t been this excited about and fascinated with a tech device in a very long time…as in, since my original experience with a Sony Walkman (yes, that long ago). It’s the kind of device that makes you look at other existing products in a profoundly different way. Having said that, with a device this different, and this expensive, you’re going to want to try it out yourself to really see if it works for you.

While the Galaxy Fold is radically different from all other smartphones in some critical ways, it’s also important to remember, however, that it is, fundamentally, still an Android phone, with all that entails. For existing Android phone owners, this means that—other than a few, simple new ways Samsung has created to work with multiple apps on the large display—it works like your existing phone. App compatibility is supposed to be very good on the Fold—though there are some apps, like Netflix, that don’t currently support multitasking windows—but it’s still too early to tell for sure.

For iPhone owners who may be tempted to switch over to the dark side (and I’m guessing there could be a reasonable number of those with this new product), it does mean getting used to Android, finding a few new apps, and—if you can handle it—giving up the blue bubbles of iOS-only threads in your messaging apps. In exchange, however, you’ll get access to an experience that Apple isn’t likely to offer for several years. Plus, given the level of multi-platform application and services support that now exists, it’s nowhere near as big a concern as it used to be.

For everyone, you’ll get six cameras—including the same three-camera package of wide angle, telephoto, and ultrawide on the S10 series—two built-in batteries, and the ability to share your battery power with others. Inside the box, you also get a set of Samsung’s Galaxy Buds wireless earbuds that can also be charged with the power sharing feature.

There’s been an enormous amount of speculation and build-up around not just the Galaxy Fold, but the foldable smartphone category in general, with many naysayers suggesting they’re little more than a gimmicky fad. While on the on one hand, I can appreciate the skepticism—we’ve certainly seen more than our fair share of products that ended being a lot less useful than they initial sounded—I really don’t think that will be the case with Galaxy Fold.

In fact, looking back historically, I wouldn’t be surprised if the release of foldables is seen as being just about as important as the release of the iPhone. It’s that big of a deal. Of course, as with the iPhone, we will undoubtedly see several iterations over time that will make the current Galaxy Fold look old-fashioned itself. But for those of us living in the present and looking to the future, the revolutionary new Galaxy Fold offers a very compelling path forward.

Google Embraces Multi-Cloud Strategy With Anthos

Let’s be honest. It’s not the easiest spot to be in. A fairly distant third place in terms of market share with some serious overhanging concerns regarding trust and privacy. Yet, that’s exactly where Google Cloud Platform (GCP) stands in relation to Amazon’s AWS and Microsoft’s Azure as they launch their 2019 Cloud Next event under the helm of Thomas Kurian, a new leader brought in to increase their business in this very competitive, yet extremely important market of cloud service providers (CSPs).

Long seen as a technology leader, Google faces the challenge of proving that they can be a good business partner as well, particularly in the enterprise market. Having had an opportunity to discuss the GCP strategy with Kurian, it’s clear he’s very focused on doing exactly that. Likely due in no small part to his long-time experience at Oracle, the new GCP President is bringing a number of basic, but essential “blocking and tackling” type of enhancements to the business. Included among them are easing contract terms, significantly building out their sales force and go-to-market efforts, simplifying pricing, and taking other steps that are designed to position the company as the kind of potential partner with whom even traditional businesses could be comfortable.

But it takes more than just basic business process improvements to make a splash in the rapidly evolving cloud computing market. And that’s exactly what the company did today with their new product announcements at Cloud Next, particularly in the red-hot area of multi-cloud with their new Anthos managed service offering.

Many businesses have been eager to have the ability to migrate their applications, particularly as concerns about lock-in with specific CSPs has served as a deterrent for further cloud adoption. By leveraging the Google-developed but open source Kubernetes container technology, along with a number of other enterprise-ready open source tools, Anthos offers a surprising flexible way to shift workloads from either AWS or Azure to GCP, and even lets companies move in the opposite direction if they so choose. Google also purchased a company called Velostrate last year that lets legacy applications wrapped in virtual machines get repackaged into containers that can also work with Anthos.

While Anthos isn’t specifically designed to be a migration tool–it’s a common platform that extends across on-premise and multi-clouds so that workloads can be run in a consistent manner across them—the ability to migrate is an important outcome of that consistency. Given the many differences in the PaaS (Platform as a Service) offerings from the various cloud providers, the seemingly simple step of migration actually requires a great deal of technological know-how and software developments to make work.

Thankfully, however, that is all hidden from software developers, as Google’s new tools are designed to let enterprise developers make the transition without any changes to their existing code. More importantly, from a psychological perspective, this freedom to move back and forth across platforms can help build trust in Google’s efforts, because it explicitly avoids (and even breaks) the lock-in issues that many companies have faced until now. In addition, it shows Google has a great deal of confidence in their own offerings, as this theoretically could be used to simply move away from GCP to other platforms. Instead, it highlights that Google now believes they can be extremely competitive on many different fronts. Plus, given the reality that GCP is likely a company’s second, or even third, cloud platform choice, the ability to use Anthos to move across platforms is a practical, and yet still strategic, advantage.

Another key benefit of the Anthos technology is the ability to see and manage applications across multiple cloud providers, as well as internally, on any private clouds via a single pane of glass. Once again, this capability gives more flexibility to organizations that are still working through their hybrid and multi-cloud strategies. In fact, in the near term, hybrid cloud environments will be the first to benefit because, while Google announced and demonstrated support for multiple cloud platforms, no specific dates were given as to when those capabilities will be generally available.

Even with these technology advancements, as well as the business process improvements, Google is still in a challenging market situation, particularly with regard to potential trust issues. While the company provided several compelling examples at their Cloud Next keynote of customers that are using the technology—and even talked about the trust several of those customers specifically said they had in Google protecting their data—the general perceptions are still a concern. Kurian acknowledged that as well but pointed out that the company is taking extraordinary steps to ensure the privacy and security of customers’ data, even to the point of logging any and all interactions that Google’s employees have with customer data (and requiring written permission to do so in the first place). Those kinds of policies are clearly important, but building trust often takes time, so Google will have to be patient there.

Thankfully, however, they are active participants in a market that demands fast technological advancements, and there is little doubt the company has the capabilities to deliver on that front. The cloud computing market continues to evolve at an extremely rapid pace, and Google’s large cloud competitors will likely react to the news with additional announcements of their own. Still, it’s clear that GCP is moving away from a purely technology-driven offering to one that’s increasingly cognizant of real-world customer needs, and that’s definitely a step in the right direction.

Is Google waiting for Apple to Popularize Mobile AR?

Google’s I/O developer conference is interesting because the company covers a lot of ground and talks about a lot of things in the keynotes. As a result, not everything that merits mainstage discussion one year is still top-of-mind for executives a year later. Still, I was somewhat surprised to see how little stage time Tango—Google’s mobile augmented reality technology—got at this year’s event. This despite the fact augmented reality has been a key focus of other recent developer conferences, including Facebook’s F8 and Microsoft’s Build. I can’t help but wonder: Is Google struggling to find progress with Tango or is it just waiting for Apple and its developers to validate the mobile AR market?

Two to Tango

Nearly a year ago, I wrote about Google’s decision to turn Project Tango into a full-fledged initiative at the company. Tango utilizes three cameras and various sensors to create a mobile augmented reality experience you view on the phone screen. By tracking the space around the phone and the device’s movement through that space, Tango lets developers drop objects into the real world. In January, I wrote about my experiences with the first Tango phone from Lenovo and noted that a second phone, from ASUS, was also on the way. More than five months later, Google executives said on stage at I/O that there are still only two announced Tango phones. Worse yet, much of the discussion around the technology was a rehash of previous Tango talking points and the one seemingly new demo failed to work on stage. In fact, aside from a video about using Tango in schools (Expedition AR), Tango’s biggest win at I/O seemed to be the fact Google is using a piece of the technology, dubbed WorldSense, to drive future Daydream virtual reality products.

My experience with Tango back in January showed the technology still had a long way to go, with the device heating up and apps crashing on a regular basis. But it also showed the potential of mobile AR. The fact is, developers can drive a pretty rudimentary mobile AR experience on most any modern smartphone, as the short-lived hype around Pokémon Go proved. But for a great experience, you need the right hardware and you need the right apps. That Google hasn’t seemed to make much progress in either, at least publicly, is surprising, as it would seem to be an area where the company has a substantial head start on Apple’s iOS and iPhone.

Waiting for Apple?

One of the biggest predictions around Apple’s next iPhone is that it will offer some sort of mobile AR experience as a key feature. Apple hasn’t said it will but CEO Tim Cook’s frequent comments about AR, and the company’s string of AR-related acquisitions, certainly point in that direction. Which has me wondering if maybe Google has slowed down on Tango because it needs Apple (and its marketing muscle) to convince consumers they want mobile AR. Or perhaps, more importantly, mobile developers should embrace the technology and create new apps.

Apple will likely ship the next version of the iPhone in September or October of this year. But the company’s Worldwide Developers Conference is happening in just a few weeks. So the question becomes: Does Apple begin to talk about augmented reality experiences on the iPhone now or later? If now, does that mean the company will support AR on existing iPhones or will only the new iPhone support the technology? As I noted last September, the addition of a second camera to the iPhone 7 Plus makes it a reasonable candidate for some AR features.

Chances are, if Apple is planning a big augmented reality push for iPhone, it already has key developers working on apps under non-disclosure agreements. But to drive big momentum, the company will need to get a significant percentage of its existing developer base to support it, too. It will be interesting to see if and what Apple discloses during the big keynote on June 5th. If Apple does put its full weight behind such an initiative, it can move the market. Such a move might jumpstart adjacent interest in Tango.

As for Google in the near-term, Daydream VR is clearly a bigger priority, as the company is working with HTC and Lenovo to bring to market standalone headset products and executives noted that more phones would soon support the technology, including Samsung’s flagship Galaxy S8 and S8+. In fact, Google predicted that, by years’ end, there would be tens of millions of Daydream-capable phones in the market. That’s the kind of scale Google likes and the kind of scale Tango can’t hope to achieve. Yet.

Google’s Fading Focus on Android

Google is holding its I/O developer conference this week and Wednesday morning saw the opening day keynote where it has traditionally announced all the big news for the event. What was notable about this year’s event, though, was what short shrift Android – arguably its major developer platform – received at the keynote and that feels indicative of a shift in Google’s strategy.

Android – The First to Two Billion

One of the first things Google CEO Sundar Pichai did when he got up on stage to welcome attendees was run through a list of numbers relating to the usage of the company’s major services. He reiterated Google has seven properties with over a billion monthly active users but also said several others are rapidly growing, including Google Drive with over 800 million and Got Photos with over 500 million. But the biggest number of all was the number of active Android devices, which passed two billion earlier this week. Now, that isn’t the same as saying it has two billion monthly active users, since some of those devices will belong to the same users as others (e.g. tablets and smartphones), while others may be powering corporate or unmanned devices. But Android is a massive platform for Google and arguably the property with the broadest reach.

Cross-platform Apps and Tools at the Forefront

Yet, Android was given only a secondary role in the keynote, a pattern that arguably began last year. Part of the reason is Google has been releasing new versions of Android earlier in the year than before, giving developers a preview weeks before I/O and then fleshing out details for both developers and users at the event, rather than revealing lots of brand new information. But another big reason is a concession to two realities that have become increasingly apparent over time. First, Google recognizes it’s lost control over the smartphone version of Android, as OEMs and carriers continue to overlay their own apps and services but also slow the spread of new versions. It takes almost two years for new versions of Android to reach half the base. Second, Google also recognizes its ad business can’t depend merely on Android users because a large portion of the total and a majority of the most attractive and valuable users are on other platforms, mostly iOS.

Together, those realities have driven Google to de-emphasize its own mobile operating system as a source of value and competitive differentiation and, instead, to focus on apps and services that exist independently of it. As such, the first hour of Google’s I/O keynote this year was entirely focused on things disconnected from Android, such as the company’s broad investment in AI and machine learning, but also specific applications like the Google Assistant and Google Photos. No transcript is available at the time I’m writing this, but I would wager one of the most frequently repeated phrases during that first hour was “available on Android and iOS” because that felt like the mantra of the morning: broadly available services, not the advantage of using Android. As Carolina pointed out in her piece yesterday, that’s not a stance unique to Google – it was a big theme for Microsoft last week too.

Short Shrift for Android

But for developers who came wanting to hear what’s new with Android, the platform the vast majority of them actually develop for, it must have made for an interesting first 75 minutes or so before Google finally got around to talking about its mobile OS and, even then, not until after talking about YouTube, which has almost zero developer relevance. When it did, Android still got very little attention, with under ten minutes spent on the core smartphone version. Android lead Dave Burke rattled through recent advances in the non-smartphone versions of Android first, including partner adoption of the Wear, Auto, TV, and Things variants, and one brief mention of Chromebooks and ChromeOS.

The user-facing features of Android O feel very much more like catch up than true competitive advantages. In most cases, they’re matching features already available elsewhere or offsetting some of the disadvantages Android has always labored under by being an “open” OS, including better memory management required by its multitasking approach or improved security required by its open approach to apps. From a developer perspective, there were some strong improvements, including better tools for figuring out how apps are performing and how to improve that, support for the Kotlin programming language, and neural network functionality.

A New Emerging Markets Push

Perhaps the most interesting part of the Android presentation was the segment focused on emerging markets, where Android is the dominant platform due to its affordability and in spite of its performance rather than because of it. The reality is Android at this point, stripped of much of its role as a competitive differentiator for Google, has fallen back into the role of expanding the addressable market for Google services. That means optimization for emerging markets.

Android One was a previous effort aimed at both serving those markets better and locking down Android more tightly but it arguably failed in both respects. It’s now having another go with what’s currently called Android Go. This approach seems far more likely to be successful, mostly because it’s truly optimized for these markets and will emphasize not only Google and its OEMs’ roles but those of developers too. That last group is critical for ensuring Android serves emerging market users well and Google is giving them both the incentives and the tools to do better. I love its Building for Billions tagline, which fits with the real purpose of building both devices and apps for the next several billion users, almost all of which will be in these markets.

Google’s YouTube Advertiser Problem has No Easy Fix

Last week, UK advertisers, including the government, the Guardian newspaper, and various others began boycotting Google’s ad products including YouTube over the fact their ads were appearing next to troublesome content, ranging from videos promoting hate to those advocating terrorism. Unsurprisingly, given the exact same issues exist here in the US, the boycott this week began to spread to Google’s home turf, with several of the largest US advertisers pulling their ads from some or all of Google’s platforms. The challenge facing Google is this problem has no easy fix – with two of three possible scenarios, either creators or advertisers will be unhappy, while Google is probably hoping a third scenario is the one that actually pans out.

The Problem

The main focus of the complaints has been YouTube, although the same problem has, to some extent, affected Google’s ads on third party sites as well. On YouTube, the root of the problem is the site has 400 hours of video uploaded every minute, making it impossible for anything but an army of human beings to view all the new content being put onto the site continuously.

As such, Google uses a combination of algorithmic detection, user flagging, and human quality checking to find videos advertisers wouldn’t want their ads to appear in and those systems are far from perfect. Terrorist videos, videos promoting anti-Semitism and other forms of hate, content advocating self-harm and eating disorders, and more have slipped through the cracks and ended up with what some perceive as an endorsement from major brands. Those brands of course, aren’t happy with that. Following some investigations by the UK press, several have now pulled their ads either from YouTube specifically or from Google platforms in general until Google fixes the problem. US brands like AT&T, Verizon, Enterprise, GSK, and others are starting to follow suit.

No Perfect Fix

From Google’s perspective, the big challenge is its existing systems aren’t working and there’s no easy way to fix that. Only one reasonable solution suggests itself and it’s far from ideal: restrict ads to only those videos which appear on channels with long histories of good behavior and lots of subscribers. That would likely weed out any unidentified terrorists, hate mongers, and scam artists without having to explicitly identify them. Problem solved! Except that, of course, the very long tail of YouTube content and creators would be effectively blacklisted even as this much smaller list of content and creators are whitelisted. That, in turn, would be unpalatable to those creators, even if advertisers might be pacified. Of course, it would have a significant effect on YouTube’s revenue too.

Given that some creators are already unhappy with what they see as the arbitrary way YouTube already determines which videos are and aren’t appropriate for advertising, going further down that route seems dangerous and will create problems of its own. But, given the current backlash against YouTube and Google more broadly over this issue, it can’t exactly keep things as they are either, because many advertisers will continue to boycott the platform and there’s likely to be a snowball effect as no brand wants to be seen as the one that’s OK with its ads appearing next to hate speech, even if others aren’t.

So, we have two scenarios, neither of them palatable. One would be essentially unacceptable to the long tail of creators and would likely significantly impact YouTube’s revenue, while the other would continue to be unacceptable to major advertisers and also would significantly impact YouTube’s revenue. To return to a point I made at the beginning, this actually is broader than YouTube to programmatic advertising in general, including Google’s ads on third party sites. Alphabet’s management has cited programmatic advertising, where humans are taken out of the picture and computers make the decisions subject to policies set by site owners and advertisers, as a major revenue driver in at least its last four earnings calls, mentioning it in that context at least seventeen times during that period.

To the extent the programmatic method of buying is a major source of the content problem at YouTube specifically and Google broadly, that’s particularly problematic for its financial picture going forward. There was already something of a backlash over programmatic advertising towards the end of last year when brand advertising was appearing on sites associated with racism and fake news but this YouTube issue has taken to the next level.

Hope of a Third Scenario

Alongside these two unappealing scenarios, there’s a third. Google must be hoping this one is what actually pans out. This third scenario would see Google making more subtle changes to both its ad and content policies than the ones I suggested above and eventually getting advertisers back on board. That approach banks on the fact brands actually generally like advertising on Google, which has massive reach and – through YouTube – a unique venue for video advertising that reaches generations increasingly disengaged from traditional TV. So I’d argue advertisers don’t actually want to shun Google entirely for any length of time and mostly want to use the current fuss to extract concessions from the company both on this specific issue and on the broader issue of data on their ads and where they show up.

Google’s initial response to the problem, both in a quick blog post on its European site last week and a slightly longer and more detailed post on its global site this week, has been along these lines. It’s accepted responsibility for some of its past mistakes, identified some specific ways in which it plans to make changes, and announced some first steps to fixing problems. However, the fact that several big US brands pulled their advertising after these steps were announced suggests Google hasn’t yet done enough. It’s still possible advertisers will come around once they see Google roll out all of its proposed fixes (some of which were only vaguely described this week) and perhaps after some additional concessions. That would be the best case scenario here. Some of the statements from advertisers this week indicate they’re considering their options and reviewing their own policies, suggesting they may be open to reconsidering.

But these current problems still highlight broader issues with programmatic advertising in general, on which advertisers won’t be placated so easily. I could easily see the present backlash turn into a broader one against programmatics in general, which could slow its growth considerably, with impacts both on Google and the broader advertising and ad tech industries. I would think Google/Alphabet would be extremely lucky to emerge from all this with minimal financial impact and I think it’s far more likely it sees both a short-term dent in its revenues and profits from the spreading boycotts and possibly a longer-term impact as brands reconsider their commitments to programmatic advertising in general.

The Tablet Computer is Growing Up

I vividly remember when the iPad first hit the scene. Much of the commentary at the time ranged from confused, to skeptical, to wildly optimistic and then some. However, very few people truly grasped the underlying shift to the touch-based computing paradigm that was underway. In fact, throughout a good portion of the tablet computer’s life, the form factor has continually fallen short of its full potential. Most were convinced this device could never be a productivity machine. These folks missed the broader reality that many millions of people were being extremely productive on their smartphones using a touch-based operating system and generations of young people would grow up with an intense familiarity and comfort level using touch-based systems as their primary computing platforms. It was this broader shift of workflows, from a mouse and pointer to ones which used touch, that I articulated in one of my first public columns back in 2010. “From Click to Touch – iPad & the Era of Touch Computing”:

It is interesting to have observed the barrier to computing a keyboard and mouse have been for so long. I was always amazed at how older generations stumbled with a keyboard and mouse, or how the biggest hurdle of learning computers for my children was the keyboard and mouse. Even my youngest, who had issues with the mouse and is just learning to read, is operating the iPad with ease and engaging in many learning games she couldn’t on the PC with the traditional peripherals. Think about the developing world and the people who never grew up with computers the way we in America have with a mouse and keyboard. How much more quickly will they embrace touch computing?

This point, which I have expanded on and further articulated through the years, has served as the basis of my bullish view on the tablet’s potential. Touch-based operating systems, built from the mobile/smartphone experience, eliminate the complexity that exists with Windows and macOS and makes computing more accessible to the masses who are, admittedly, not the most technology literate people. Mobile operating systems like iOS and Android abolish the need for tech literacy classes yet still yield the same potential end results in creativity and productivity as any desktop OS.

In the years since the iPad’s launch, the broad observation of the power in touch/mobile operating systems has manifested itself with Windows and the PC ecosystem creating products more like tablets, Apple with the iPad Pro, and now Samsung with the Galaxy Tab S3 just announced at Mobile World Congress looking to make tablets more like PCs.

However, now we are several years down the road. My concern is tablets have not gained as much ground on the PC as the PC has gained on tablets. It’s true iPad has tens of thousands of dedicated apps and both iPad and Android tablets are utilized in enterprises for mobile workforce computers but, when it comes to the average consumer, they are still not turning from their PCs to iPads or Android tablets as a replacement. In a research study we did in the second half of 2016 on consumers usage and sentiment around PCs and tablets, 67% of consumers had not even considered replacing their PC/Mac with an iPad or Android tablet.

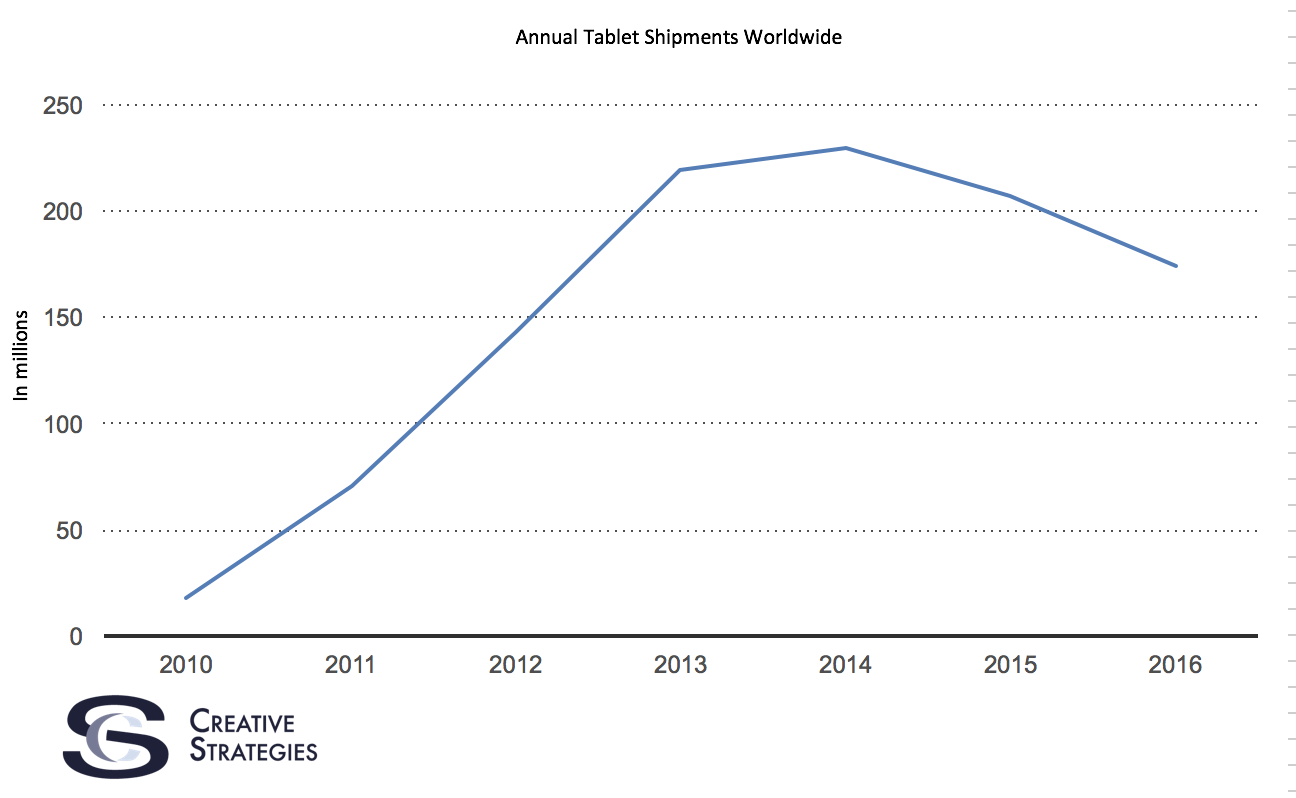

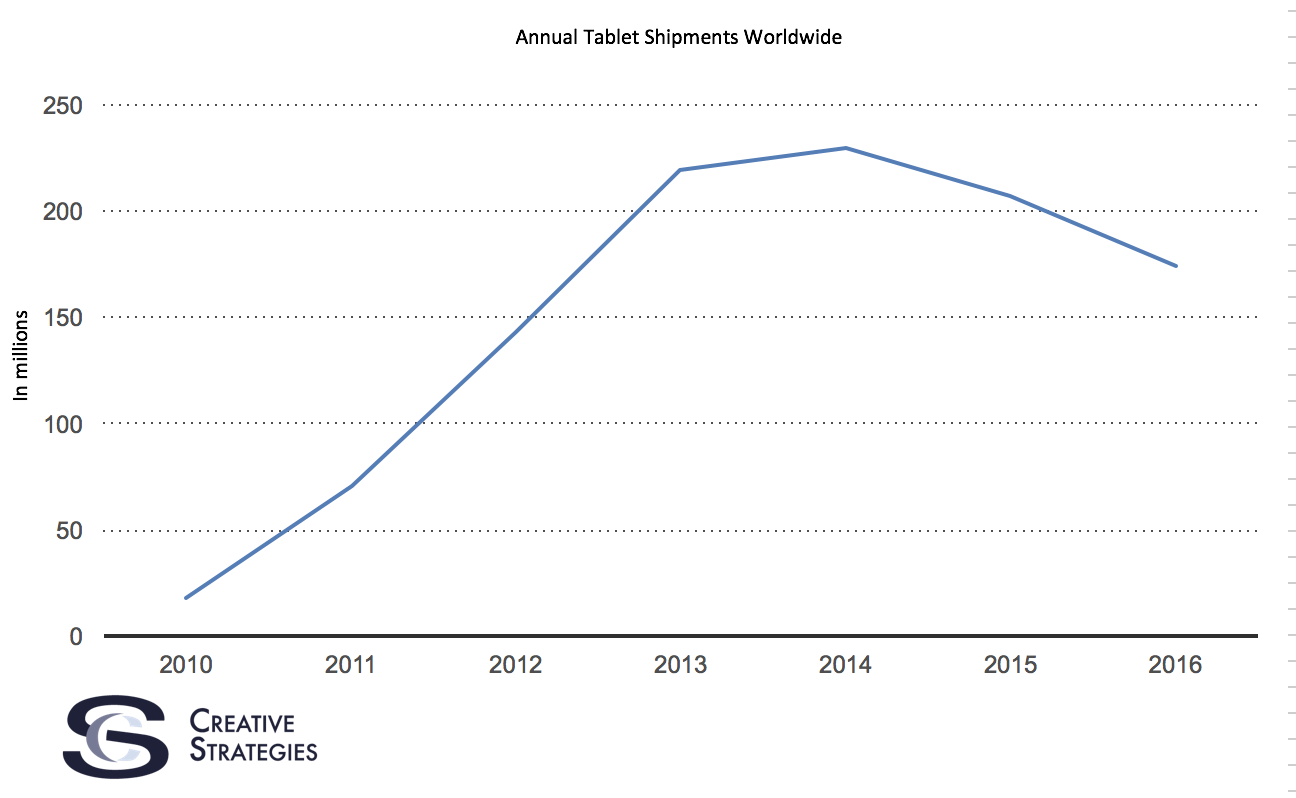

As you may have seen, the tablets trend line is not encouraging.

While it is true the PC trendline isn’t much better, over the past year or so a fascinating counter-trend has been happening in the PC industry. The average selling price of PCs is actually increasing. In the midst of the tablet decline, many consumers are realizing they still need a traditional laptop or desktop and are spending more on such computers than in many years past. Our research suggests a key reason is because consumers now understand they want a PC which will last since they will likely keep it for 6 years or more. They understand spending to get a quality product, one that won’t break frequently or be a customer support hassle, is in their best interests and they are spending more money on PCs than ever before. This single insight is a key source of my concern for the tablet category.

Another key data point in the tablet and PC conversation is how the tablet continues to fall by the wayside when it comes to the most important device to consumers. While the smartphone is the obvious choice consumer pick as most important, the tablet still ranks lower than both desktops and laptops — this is true of iPad owners as well. Tablets and the iPad have yet to overwhelmingly move from luxury to necessity for the vast majority.

I’m still as bullish as ever on the tablet’s potential. However, my concern is consumers may be extremely stubborn and lean heavily on past behavior and familiarity with PCs instead of going through the process to replicate the workflows and activities they did on their PCs and transition to tablets. This is a year where Apple needs to take great strides in software around iOS for iPad if they want the iPad to become more than it is today and truly rival the PC in the minds of the consumer. While tablets have no doubt grown up, they still have a little more growing to do if they want to truly challenge the PC and Mac.

Living the Daydream: Google’s New VR Platform takes Shape

I’ve been testing hardware that runs Google’s virtual reality (VR) platform called Daydream. It’s a little rough around the edges and is clearly pushing its brand new hardware to its limits. But overall, it’s a pretty good experience and it shows the potential for mainstream VR going forward. That said, my time inside Daydream further cemented my view that VR today is somewhat exhausting, rather isolating, and is best in small doses.

Soft and Cozy Face Hugger

I tested Daydream using Google’s Pixel XL smartphone and Daydream viewer. When Google announced Daydream at its I/O conference, I thought its viewer would have more technology onboard than the Cardboard-based viewers the company had been pushing as a low-cost entry to VR for years. Cardboard viewers are often literally made from cardboard, although there are plenty of nicer ones out there. In reality, however, the Daydream viewer itself has very little silicon inside its fabric-wrapped shell, aside from an NFC chip. This chip alerts the Pixel you’re about to strap it into the viewer, launching the Daydream interface.

There are some key differences between Cardboard and Daydream. Chief among them is that to run Daydream, an Android phone must have the right combination of processing power and sensors. I’ve never been able to use a Cardboard viewer, even a good one, for more than 5-10 mins without feeling nauseous. But I didn’t experience that this time which I attribute to these hardware requirements. Second, the Daydream viewer includes a Bluetooth controller that fundamentally changes how you interact with content inside the viewer. The result is an experience dramatically more intuitive and immersive than any I’ve experienced within a Cardboard viewer.

After you walk through a tutorial on using the remote (which includes two buttons and touchpad area), you can dive right into the content. As you might expect, Google’s own content is front and center with YouTube VR and Google Play store preloaded. I’ve had the phone and viewer for about a week and, in that time, Google seems to have added more content to both. Today, there are about 60 apps available through the store. These include games, streaming apps such as Netflix and Hulu (where you can watch standard videos on a giant screen), as well as VR-specific content aggregators such as LittleStar and NextVR. As you might expect, some of the content is good but much of it is cheesy and gimmicky. There’s no denying that, when you hit upon something cool in VR, it’s a very exhilarating experience.

Is it Hot in Here?

Unfortunately, at least for me, these experiences are still best enjoyed in brief bursts. While Daydream is certainly a better experience than Cardboard, I still find myself limited to a maximum of 20-25 minutes in the viewer. Part of the issue is my eyes and brain just seem to find VR experiences taxing (I’m also not a big fan of 3D movies). Another problem is when the Pixel is working hard it gets hot to the touch. Not warm, but hot, and that heat gets transferred to your face. After a short while, it gets warm enough to be uncomfortable. And when you remove the viewer, you look like a red raccoon.

I’ve yet to stay in VR long enough to have the phone actually overheat. But, on numerous occasions, I’ve had it drop out of VR mode into standard phone mode. It’s not clear if this is a glitch, user error, or a bit of both. But it does necessitate taking off the headset, removing the phone, and starting the process over. Like I said, a little rough around the edges.

There are other basic interface challenges Google and its partners still need to address. For example, it’s possible to log into your Netflix and Hulu accounts through the VR interface but, if you need to look up your passwords in a manager app, you have to drop out of VR to do so (at least until those apps make their way to VR). Of course, should a friend or family member try to talk to you while you’re inside Daydream with headphones on, they’re probably going to have to tap you on the shoulder. This can lead to bigger jump scares than anything that happens in VR.

At the end of the day, that’s my biggest issue with VR: It’s a fairly lonely place. I know Facebook is planning to drive a social component with Oculus and I would expect Google and others to try to do so at some point as well. Maybe these future social elements will change my thinking. For now, VR requires a level of isolation I find uncomfortable. Which means, at least for the near term, all of my virtual experiences will need to clock in at 30 minutes or less.

Has Google Set Up Google Home to Disappoint?

When I saw Google Home for the first time back at Google I/O, I was excited at the prospect of having a brainier Alexa in my home. Like others, I waited and almost forgot all about it until it was reintroduced last month when I actually could go and pre-order it.

I got my Google Home at the end of last week and placed it in the same room Alexa has been calling home for almost a year now. The experience has been interesting, mainly because of the high expectations I had.

Making comparisons with Echo is natural. There are things that are somewhat unfair to compare because of the time the two devices have been on the market and therefore the different opportunity to have apps and devices that connect to them. There are others, though, that have to do with how the devices were designed and built. I do not want to do a full comparison as there are many reviews out there that have done a good job of that but I do want to highlight some things that, in my view, point to the different perspective Amazon and Google are coming from when it comes to digital assistants.

Too early to trust that “it just works”

Like Echo, Google Home has lights that show you when it is listening. Sadly, though, it is difficult to see those lights if you are not close to the device as they sit on top rather than on the side like the blue Echo lights that run in circles while you are talking to Alexa. This, and the lack of sound feedback, make you wonder if Google Home has heard you or not. You can correct that by turning on the accessibility feature in the settings which allow for a chime to alert you Google Home is engaged.

It is interesting to me that, while Amazon thought the feedback actually enhanced the experience of my exchange with Alexa, Google did not think it was necessary and, furthermore, something that had to do with accessibility vs. an uneasiness in just trusting I will be heard. This is especially puzzling given Echo has seven microphones that clearly help with picking up my voice from across the room far better than Google Home.

The blue lights on the Echo have helped me train my voice over time so I do not scream at Alexa but speak clearly enough for her to hear even over music or the TV. This indirect training has helped, not just with efficiency, but it has also made our exchanges more natural.

OK Google just doesn’t help bonding

I’ve discussed before whether there is an advantage in humanizing a digital assistant. After a few days with Google Home, my answer is a clear yes. My daughters and I are not a fan of the OK Google command but, more importantly, I think there is a disconnect between what comes across like a bubbly personality and a corporate name. Google Assistant – I am talking about the genie in the bottle as opposed to the bottle itself – comes across as a little more fun than Alexa from the way it sings Happy Birthday to the games it can play with you. Yet, it seems like it wants to keep its distance which does not help in building a relationship and, ultimately, could impact our trust. I realize I am talking about an object that reminds you of an air freshener but this bond is the key to success. Alexa has become part of the family from being our Pandora DJ in the morning to our trusted time keeper for homework to my daughter’s reading companion. And the bond was instant. Alexa was a ‘she’ five minutes out of the box. While Google Assistant performs most of the same roles, it feels more like hired help than a family member.

Google Assistant is not as smart as I hoped

The big selling point of Google Home has been, right from the get go, how all the goodness of Google search will help Google Assistant be smarter. This, coupled with what Google knows about me through my Gmail, Google docs, search history, Google Maps, etc., would all help deliver a more personalized experience.

Maybe my expectations were too high or maybe I finally understand being great at search might not, by default, make you great at AI. I asked my three assistants this question: “Can I feed cauliflower to my bearded dragon?” Here is what I got:

Alexa: um, I can’t find the answer to the question I heard

Siri: Here is what I found… (displayed the right set of results on my iPhone)

Google Assistant: According to the bearded dragon, dragons can eat green beans…

Just in case you are wondering, it is safe to feed bearded dragons cauliflower but just occasionally!

Clearly, Google Assistant was able to understand my question (I actually asked multiple times to make sure it understood what I had said) but pulled up a search result that was not correct. It gave me information about other vegetables and then told me to go and find more information on the bearded dragon website. The first time I asked who was running for president I received an answer that explained who can run vs who was running. Bottom line, while I appreciate the attempt to answer the questions and I also understand when Google Assistant says, “I do not know how to do that yet but I am learning every day”, the experience is disappointing.

Google is, of course, very good at machine learning as it has shown on several occasions. I could experience that first hand using the translation feature Google Home offers. I asked Google Assistant how to say, “You are the love of my life” in Italian. I got the right answer delivered by what was clearly a different voice with a pretty good Italian accent. Sadly, though, Google Home could not translate from Italian back into English which means my role as a translator for my mom’s next visit will not be fully outsourced.

We all understand today’s assistants are not the real deal but rather, they are a promise of what we will have down the line. Assistant providers should also understand that, with all the things the assistants are helping us with today, there is an old fashioned way to do it which, more likely than not, will be correct. So, when I ask a question I know I can get an answer to by reaching for my phone or a computer or when I want to turn the lights off when I know I can get up and reach for the switch. This is why a non-experience at this stage is better than the wrong experience. In other words, I accept Google Assistant might not yet know how to interpret my question and answer it but I am less tolerant of a wrong answer.

Google Assistant is clearly better at knowing things about me than Alexa and it was not scared to use that knowledge. This, once again, seems to underline a difference in practices between Amazon and Google. When I asked if there was a Starbucks close to me, Google Assistant used my address to deliver the right answer. Alexa gave me the address of a Starbucks in San Jose based on a zip code. Yet, Alexa knows where I live because Amazon knows where I live and my account is linked to my Echo. Why did I have to go into the Alexa app to add my home address?

Greater Expectation

Amazon is doing a great job adding features and keeping users up to speed with what Alexa can do and I expect Google to start growing the number of devices and apps that can feed into Google Home. While the price difference between Google Home and Echo might help those consumers who have been waiting to dip their toes with a smart speaker, I feel consumers who are really eager to experience a smart assistant might want to make the extra investment to have the more complete experience available today.

We are still at the very beginning of this market but Google is running the risk of disappointing more than delighting at the moment. Rightly or wrongly, we do expect more from Google especially when we are already invested in the ecosystem. We assume Google Assistant could add appointments to my calendar, read an email or remind me of upcoming event and, when it does not, we feel let down. The big risk, as assistants are going to be something we will start to engage more with, is consumers might come to question their ecosystem loyalty if they see no return in it.

The Best Automotive Tech Opportunity? Make Existing Cars Smarter

Everyone, it seems, is excited about the opportunity offered by smart and connected cars. Auto companies, tech companies, component makers, Wall Street, the tech press, and enthusiasts of all types get frothy at the mouth whenever the subject comes up.

The problem is, most are only really excited about a small percentage of the overall automobile market: new cars. In fact, most of the attention is being placed on an arguably even smaller and unquestionably less certain portion of the market: future car purchases from model year 2020 and beyond.

Don’t get me wrong; I’m excited about the capabilities that future cars will have as well. However, there seems to be a much larger opportunity to bring smarter technology to the hundreds of millions of existing cars.

Thankfully, I’m not the only one who feels this way. In fact, quite a few companies have announced products and services designed to make our existing cars a bit smarter and technically better equipped. Google, T-Mobile, and several lesser-known startups are beginning to offer products and services designed to bring more intelligence to today’s car owners.

While there hasn’t been as much focus on this add-on area, I believe it’s poised for some real growth, particularly because of actual consumer demand. Based on recent research completed by TECHnalysis Research and others, several of the capabilities that consumers want in their cars are relatively straightforward. Better infotainment systems and in-car WiFi, for example, are two of the most desired auto features, and they can be provided relatively easily via add-on products.[pullquote]I’m excited about the capabilities that future cars will have, but there seems to be a much larger opportunity to bring smarter technology to the hundreds of millions of existing cars.”[/pullquote]

On the other hand, while fully autonomous driving may be sexy for some, the truth is, most consumers don’t want that yet. As a result, there isn’t going to be a huge demand for what would undoubtedly be difficult to do in an add-on fashion (though that isn’t stopping some high-profile startups from trying to create them anyway…but that’s a story for a different day).

In the case of Google, the company’s new Android Auto app puts any Lollipop (Android 5.0)-equipped or later Android phone into an auto-friendly mode that replicates the new in-car Android Auto interface. The screen becomes simplified, type and logos get bigger, options become more limited (though more focused), and end users start to get a feel for what an integrated Android Auto experience would be like—but in their current car.

The quality of the real-world experience will take some time to fully evaluate, but the idea is so simple and so clever that you have to wonder when Apple will offer their own variation for CarPlay (and maybe why they didn’t do it first…).

T-Mobile partnered with Chinese hardware maker ZTE and auto tech software company Mojio to provide an in-car WiFi experience called SyncUP DRIVE that leverages an OBD-II port dongle device that you plug into your car (most cars built since 1996). While several other carriers offer OBD-II dongles for no cost (you do have to pay for a data plan in all cases), the new T-Mo offering combines the WiFi hotspot feature with automotive diagnostics in a single device thanks to the Mojio-developed app.

Several startups I’ve come across also have other types of in-car tech add-ons in the works, many of which are focused on safety-applications. I’m expecting to see many compute-enabled cameras, radar, and perhaps even lidar-equipped advanced driver assistance systems (ADAS) add-ons at next year’s CES show, some of which will likely bring basic levels of autonomy to existing cars. The challenge is, the more advanced versions of these solutions need to be built for specific car models, which will obviously limit their potential market impact.

Car tech is clearly an exciting field and it’s no surprise to anyone that it’s becoming an increasingly important purchase factor, particularly for new cars. However, it may surprise some to know that the in-car tech experiences still lag the primary car purchase motivators of price, car type, looks, performance, etc. In that light, giving consumers the ability to add-on these capabilities without having to purchase a whole new car, seems to make a lot of sense—especially given the roughly decade-long lifetime for the average car.

Obviously, add-ons can’t possibly provide the same level of capabilities that a grounds-up design can bring, but many consumers would be very happy to bring some of the key capabilities that new cars offer into existing models. It’s going to be an exciting field to watch.

The First Time Google Alerted Me to Leave for an Appointment

The first time Google alerted me to leave for an appointment, it was one of those “Aha!” moments. I thought to myself, “That’s amazing!” as I realized it was smart enough to check my calendar, learn where and at what time my appointment was, calculate the time I needed to leave to arrive on time, and then sent me an alert to depart.

But how quickly we adapt and take much of this for granted. Now there are numerous apps that make decisions and are trying to think for us. They monitor our email, calendar, and location and, using artificial or some other sort of intelligence, take action we’d normally do on our own.

TripIt will detect when you’re emailed an itinerary from an airline and add the flights to your calendar. Waze will determine when a traffic jam occurs and route you around it. Google will determine when an appointment invite is emailed to you and put it on your calendar. So many apps now have this level of intelligence to create an action without our intervention.

I’m finding, however, as this occurs more frequently, there are numerous errors that occur. I need to intervene more often and make corrections because the assumptions these apps make are usually based on fairly primitive logic. Not every mention in an email is meant to be actionable. Not every itinerary is yours and needs to be scheduled. While the apps try to be helpful, there are many times they get it wrong; perhaps 25% of the time.