On January 10, 2016, I wrote an article entitled, “Platforms — Past, Present and Future“. The comments on the article made it clear to me there was massive confusion surrounding the meaning and purpose of branding in general and value, premium and luxury branding in particular.

This is part two of a four part series on and around branding. Part 1, “Android is a Stick Shift and iOS is an Automatic Transmission”, can be found here. Part two focuses on Brands and how they are used by tech companies, in general.

If you don’t know jewelry, know the jeweler. ~ Warren Buffett

Few of us know anything about the products we’re purchasing and even fewer of us know a trusted expert to advise us. Brands are a communication tool for the seller and a shortcut to understanding the product being purchased for the buyer.

Definitions

Brand Equity

Brand equity — or simply ‘Brand’ — is the premium a company can charge for a product with a recognizable name, as compared to its generic equivalent. Companies can create a brand for their products or services by making them memorable or easily recognizable or superior in quality or reliability.

A brand’s value is merely the sum total of how much extra people will pay, or how often they choose…one brand over the alternatives. ~ Seth Godin

Commodity

The opposite of a brand is a commodity item with little or no perceived differentiation from like products.

Differentiate or die ~ Jack Trout

A commodity is merely one of many options available to the consumer. When every product is nearly the same and price is the only significant differentiator, consumers don’t look for the best brand, they look for the best price.

Remember my mantra: distinct… or extinct. ~ Tom Peters

Value Brand

A Value Brand has one or more significant advantages over its competitors — distribution, automation, location, limited availability, etc. — but the primary way in which Value Brands attract their customers is via lower prices.

There are two kinds of companies, those that work to try to charge more and those that work to charge less. We will be the second. ~ Jeff Bezos

Some well known value brands are K-Mart, Walmart Amazon and IKEA.

Let me make one thing very clear. There is absolutely nothing wrong with or inferior about a Value Brand. A Value Brand may charge less but that doesn’t make them less of a brand. Value Branding is just one of several different — and highly successful — branding strategies. The vast majority of the items we own and use every day are purchased from Value Brands.

Premium Brand

A Premium Brand is a Brand that holds a unique value in the market through design, engineering or quality. Premium goods are more expensive, i.e., they charge a “premium” because they have, and maintain, a significant advantage over competing products. Some examples of Premium Brands are Disney, American Express credit cards, and Bose speakers.

More than a 1-to-1 ratio of profit share to market share demonstrates a company’s ability to differentiate its products, provide more value than its competitors, command higher prices, charge a premium and enjoy pricing power. ~ ~ Bill Shamblin

Corollary: Business is hard because differentiation – for which you can charge a premium – is hard. ~ Ben Thompson (@monkbent)

Veblen

The extra features of a Premium Brand provide the justification for its higher prices vis-à-vis a Value Brand. On the other hand, a Luxury Brand’s price greatly exceeds the functional value of the product. Qualities common to Luxury Brands are over-engineering, scarcity, rarity or some other signal to customers that the quality or delivery of the product is well beyond normal expectations. The Luxury Brand’s extraordinary excesses provide a rationale for the buyer to pay the brand’s extraordinary prices.

We’re overpaying…but [it’s] worth it. ~ Samuel Goldwyn

People can, and do, argue endlessly about where the line between Premium and Luxury Brands should be drawn. However for our purposes, the difference between Premium and Luxury is not so consequential that we need to delve into those nuances. What is important is understanding the concept of Veblen goods.

Give us the luxuries of life, and we will dispense with its necessaries. ~ John value Motley

Veblen goods are luxury goods — such as jewelry, fashion designer handbags, and luxury cars — which are in demand precisely BECAUSE they have higher prices. The high price encourages favorable perceptions among buyers and make the goods desirable as symbols of the buyer’s high social status. Veblen goods are counter-intuitive because they run against our understanding of how the laws of supply and demand are supposed to work.

I have the simplest tastes. I am always satisfied with the best. ~ Oscar Wilde

Some Brand examples of Veblen Goods are Chanel, Louis Vuitton, BMW, and Mont Blanc. Rolex for example, has created a watch to work at up to 200 meters below sea level. Who the heck is going to be fool enough to go scuba diving while wearing a Rolex watch? However, this is exactly the kind of over-the-top quality that helps buyers justify their luxury purchases.

One way to distinguish a Premium Brand from a Veblen Brand is to project what would happen if the brand’s prices were lowered. A significant decrease in the price of a Premium Brand would likely increase sales, while simultaneously decreasing margins. However, a significant decrease in the price of a Veblen Brand would likely DECREASE sales (and decrease margins) because the lowered price would destroy the brand’s cachet.

Although Veblen products are very prominent and therefore receive lots of attention, they are also fairly rare, at least in proportion to the Premium and Value Brands in their respective categories.

Question: Why Don’t More Companies Become Premium Brands?

Most companies don’t strive to become Premium Brands because it’s entirely unnecessary. Being a Value Brand is a very legitimate and very profitable strategy. Walmart is a Value Brand and it’s one of the richest companies on the planet.

Second, most companies don’t strive to become Premium Brands because Premium is hard. And moving from Value to Premium is even harder.

Half of being smart is knowing what you’re dumb at. ~ Solomon Short

Companies that try to become Premium Brands are like kids that try to have sex in high school. They all want to do it. They all claim they’re doing it. Few of them are actually doing it. And those who are doing it are doing it badly.

Once you start in the low-end in this country it is very hard to move up. ~ Ben Bajarin on Twitter

Trying to leapfrog from one brand category into another is like trying to leapfrog a unicorn. Very tricky. Very dangerous.

Question: Why Not Sell To Both Value And Premium Customers?

As I pointed out in last week’s article (Android is a stick shift and iPhone is an automatic transmission), while you can simultaneously appeal to both Value and Expert buyers, you cannot simultaneously appeal to both Value and Premium buyers. Not that many, many companies haven’t tried.

No man can serve two masters: for either he will hate the one, and love the other; or else he will hold to the one, and despise the other. ~ New Testament, Matthew 6:24

No Brand can serve two masters either.

It’s really, really tough to make a great product if you have to serve two masters. ~ Phil Libin, Evernote CEO

The ever present temptation is to chase sales by broadening one’s product portfolio, opening up distribution or even discounting products. This can cause real long term damage to the brand.

Never purchase beauty products in a hardware store. ~ Addison Mizner

People do not want to buy beauty products in a hardware store and they don’t want to buy Premium products from a Value Brand either. Do you go to K-Mart to buy high end goods? Do you go to Tiffany’s expecting to get a bargain?

Brands are always at risk of being caught in the deadly middle. Mix your brands, mix your message and your Brand will not appeal to both Value and Premium customers — it will appeal to none.

It is not wise to violate the rules unless you know how to observe them. ~T.S. Eliot

Gucci, and Pierre Cardin are recent examples of premium/luxury Brands that overexposed their Brand. Who wants to pay extra for clothes everybody else is wearing?

Samsung is an example of a Value Brand that tried to stretch to cover Premium as well. Who wants to buy a Premium phone from a Value provider?

Sparrows that emulate peacocks are likely to break a thigh. ~ Burmese proverb

Fire, water and markets know nothing of mercy. Stray from your brand and your customers will stray from you.

Some Examples Of Tech Brands

It is a test of true theories not only to account for but to predict phenomena. ~ William Whewell

Microsoft Windows (for PCs)

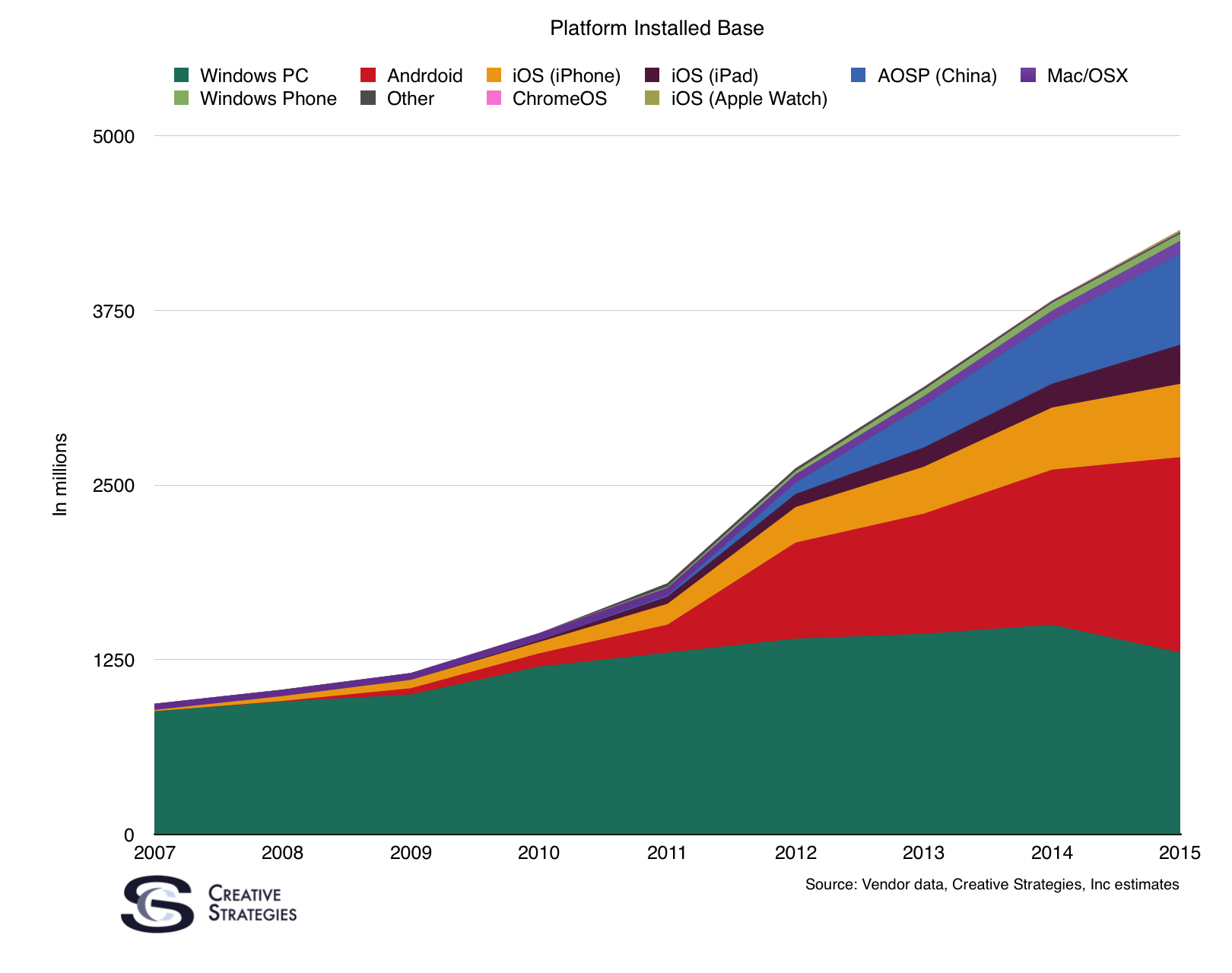

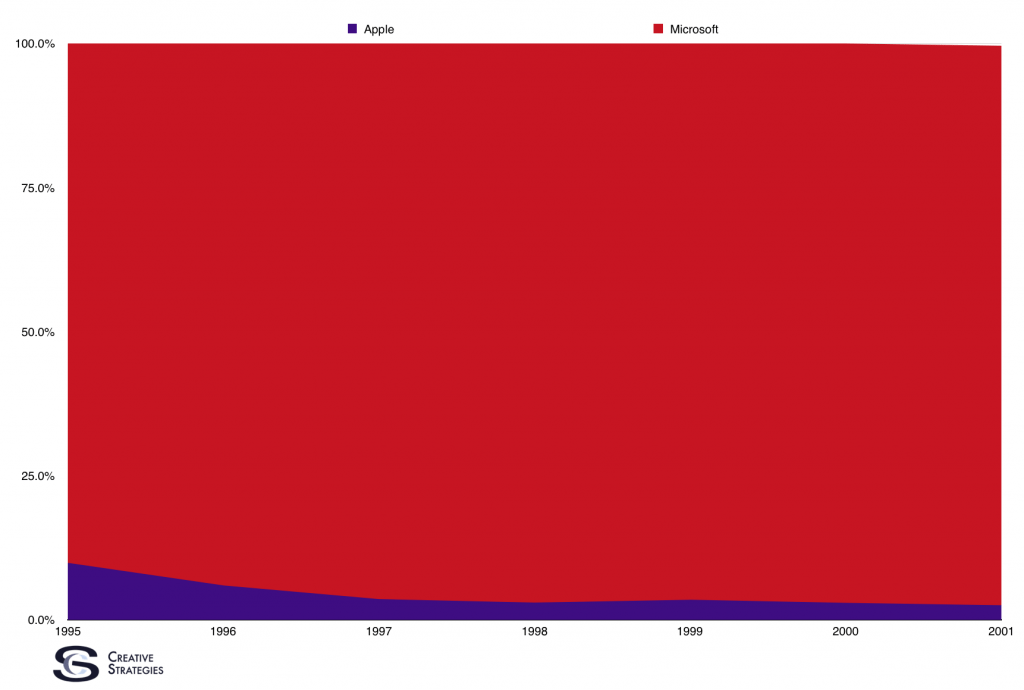

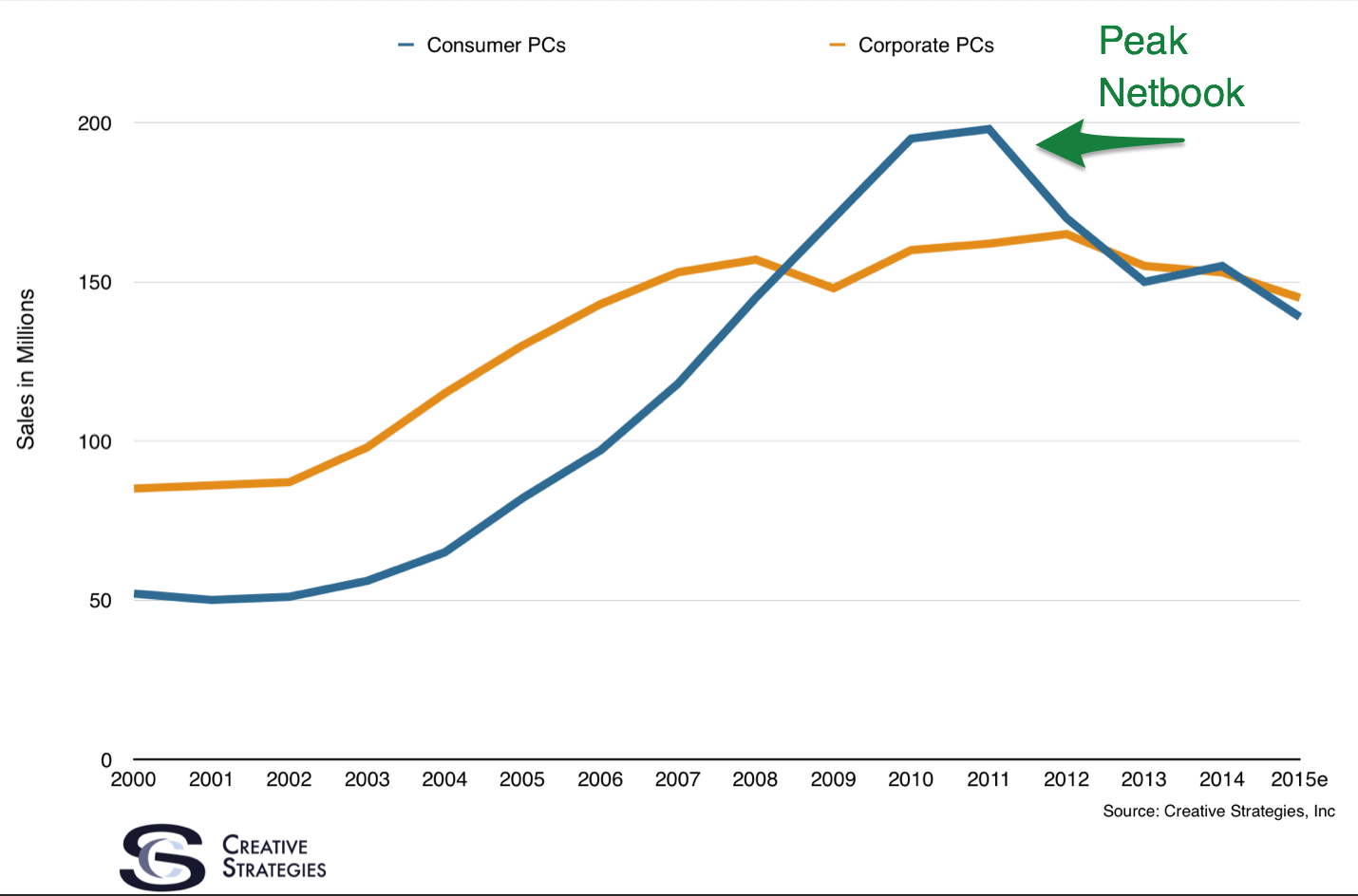

The Windows near-monopoly that existed for the past two decades was an anomaly, not the norm. When everyone has to buy the same product, the lines between Value, Premium and Veblen Brands become blurred. As soon as mobile computers provided significant competition to the Windows near-monopoly, customer segmentation quickly returned.

Microsoft Windows Phone

Microsoft has had numerous problems associated with its Windows Phone, but one of the problems is the Windows Phone did not neatly fit into any one Brand category. Microsoft wanted the Windows Phone to be a Premium Brand that could compete with the iPhone but, because Windows Phone was so late to market, Microsoft initially sold the phone at discount prices in order to gain market share. The phone’s lack of identity was undoubtedly one of the reasons why it was never able to gain traction against its Value and Premium competitors.

Windows Phone’s biggest challenge: it has neither scale of Android nor premium base of iOS. ~ Jan Dawson

IKEA

IKEA is not a tech brand, but I list it here because it is a fascinating compare. IKEA is very Apple-like in design and very Value-like in Brand. It’s a unique combination and Brand that’s led IKEA to a unique level of Brand identity and corporate success. IKEA has no secrets. Anyone can copy the products they sell. Yet no one does. IKEA has been doing the same thing for 40 years but they also have no virtually no competitors. They have carved out an identity for themselves that is virtually unassailable.

Amazon Fire Phone

Amazon is an amazingly successful Value Brand. Once again, I refer you to Jeff’s Bezos’ clearly stated company philosophy:

There are two kinds of companies, those that work to try to charge more and those that work to charge less. We will be the second. ~ Jeff Bezos

You cannot have a corporate mindset that you are going to charge less than the competition and then turn around and attempt the sell Premium products. Whenever Amazon does stray into the premium sector, they usually receive a bloody nose. The latest case in point is the Amazon Fire Phone.

I greatly admire Jeff Bezos who is far, far smarter than I am, but I think Amazon would be better served if it stuck to its knitting.

Fitbit Blaze

Fitbit is a Value brand. When they recently strayed into the premium sector with the Blaze, the stock market smacked them. Investors and consumers just didn’t believe Fitbit could play as an equal with Apple in the Premium wearable arena.

Samsung Galaxy

Samsung is a Value Brand that had aspirations of becoming a Premium Brand. Or perhaps it would be more accurate to say Samsung has aspirations of becoming both a Value Brand AND a Premium Brand.

Almost exactly four years ago, Samsung’s marketing boss sat down for an interview and made a claim that seemed almost comical at the time. … People had been obsessed with Apple’s iPhone line for long enough, and Samsung was going to shift their obsession to Galaxy phones. ~ Zach Epstein, BGR

And for a while, it seemed like Samsung had pulled off their audacious goal of challenging the Apple iPhone in the Premium sector. With a massive smartphone division and tens of billions of dollars to spend on marketing, Samsung’s star seemed to be waxing while Apple’s appeared to be waning. But it was not to be.

Samsung’s smartphone growth has come grinding to a halt. And it’s not because the company’s phones aren’t as good as they once were, or because Samsung’s advertising has slowed down. In both cases, the truth is quite the opposite — the Galaxy S6 and Note 5 are two of the most impressive smartphones that have ever existed, and Samsung’s marketing budget is still 11 digits each year. It’s also certainly not because Samsung is running out of room to grow; an estimated 1.4 billion smartphones shipped in 2015.

The bottom line is this: Samsung’s best smartphones simply aren’t exciting anymore. ~ Zach Epstein, BGR

By trying to sell to both the Value buyers and the Premium buyers, Samsung fell into the deadly middle. Apple stole away Samsung’s Premium customers from above while Xiomi and others undercut Samsung’s Value proposition from below.

Google Android

Android is a Value Brand because, despite its many significant features, the feature that most distinguishes Android and its associated products and services from those of its competitors is lower price.

People think I’m insulting Google when I call them a Value Brand.

First, being a Value brand is not an insult.

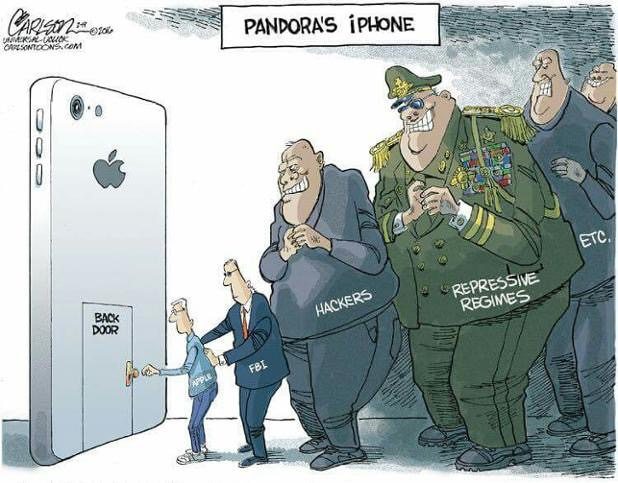

Second, Google Android not only is a Value Brand, Google WANTS Android to be a Value Brand and NEEDS Android to be a Value Brand. Android’s purpose is to extend Google’s reach — to have Android on billions and billions of phones. The more people use Android, the more information Google has access to.

Google Android’s entire business model is based on value. They give away the software for free, which allows manufacturers to sell their phones cheaper, which allows more buyers to buy smartphones, which puts Google services in more pockets everywhere. It’s a brilliant business model that has succeeded brilliantly. To claim Android is, or should aspire to be, anything other than a Value Brand is to not understand Google’s purpose in creating Android.

To be fair, Google has tried and tried and tried to go up market with the Nexus phone and, while the press has often been all agog over them, the buying market has all but ignored them.

While industry writers like to talk about how Google has “80 percent” share with Android, the actual units of Google-branded devices that compete with Apple are quite negligible (0.1 percent, according to IDC), despite the huge share of media attention provided to it. The number of people buying Nexus phones is less than even Windows Phone, and you’d be hard pressed to find any reasonable person who actually believes that Microsoft materially competes with Apple in the smartphone market. ~ Daniel Eran Dilger, AppleInsider

At best, the Nexus is the equivalent of a concept car. At worst, it’s a sign of misguided strategic vision.

RIM Blackberry

In its day, Blackberry was definitely a premium product. It was a best-in-class emailing machine. Geeky, yes. But very powerful.

We think of the BlackBerry device as the greatest communication device on the planet, one which enables you –a push environment, a reliable device. It’s the platform that enables this. ~ Anthony Payne, Director of Platform Marketing, Research In Motion, 13 May 2011

The above was absolutely true in 2006, but it was absolutely untrue when the above was written in 2011. By then, the iPhone had supplanted Blackberry in the Premium smartphone category.

What happened to Blackberry was a technology paradigm shift. The iPhone was as different from the Blackberry as the the steamship was different from the sailing ship. The Blackberry was a premium “sailing ship” but, in the long run, it couldn’t even begin to compete with the Value, more less the Premium, smartphone steamships that followed it.

Once a new technology rolls over you, if you’re not part of the steamroller, you’re part of the road. ~ Stewart Brand

Disney

Disney is a Premium Brand. I include Disney because I see a lot of parallels between Disney’s Brand and Apple’s Brand. Disney holds a very tiny percentage of the theme park market, yet they have a commanding grip on the top of that market. Disney could easily afford to create hundreds of additional theme parks, but to do so would diminish, rather than enhance, their product’s appeal.

Apple Watch

Apple Watch Edition ranges in price from $10,000 to $17,000 and it is unquestionably a Veblen Good. The price of the Apple Watch Edition is significantly greater than the price of the Apple Watch Sport and the Apple Watch without a corresponding increase in quality or functionality.

The Apple Watch has displaced Rolex on a list of luxury global brands, as measured by analytics firm NetBase…. ~ Luke Dormehl, Cult Of Mac

I don’t know whether the Apple Watch Edition will actually out-luxury Rolex watches, but I do know Rolex is exactly the type of Veblen good that the Apple Watch Edition is competing against.

Next Week

There are two great rules of life: never tell everything at once. ~ Ken Venturi

Next week I will focus on Apple’s Branding. Is the iPhone truly deserving of its Premium status or is it merely using the smoke and mirrors of marketing to fool us into believing it is a premium product? Or perhaps the iPhone isn’t a Premium product at all, but is a Veblen good instead. Join me next week at which time I will fail to answer these questions and many, many more.