These days, there are a lot of questions swirling around Apple and the biggest question of all is whether Apple has forgotten how to innovate.

Of course, this question is not new.

The company once notorious for its ability to upend convention and revolutionize markets may no longer have what it takes, worry some technology journalists. Call it the iPad or the iPlod, but the message seems clear: Apple may have lost its mojo. ~ Jeremy A. Kaplan, FOXNews.com, 28 January 2010

I was talking recently to someone who knew Apple well, and I asked him if the people now running the company would be able to keep creating new things the way Apple had under Steve Jobs. His answer was simply ‘no.’ I already feared that would be the answer. I asked more to see how he’d qualify it. But he didn’t qualify it at all. No, there will be no more great new stuff beyond whatever’s currently in the pipeline. So if Apple’s not going to make the next iPad, who is? ~ Paul Graham, March 2012

Two years ago I wrote that without its charismatic founder, Apple would move from being a great company with high growth and high innovation to being a good company with moderate growth and attenuated innovation. After this week’s set of announcements, I stand by that analysis. ~ George Colony, Bloomberg, “Apple Follows” September 2, 2014

Key take aways: Innovation at Apple is over… Just incremental improvements, nothing ground breaking. The best is over for Apple. iPad mini is playing catch up to Google Android, probably will have a mediocre customer adoption. ~ Trip Chowdhry, Global Equities, 23 October 2012

Remember when the iPhone was truly innovative? Think hard, because you’d have to go back to 2007, and the release of the first iPhone. But since then, Apple has been tossing out retread after retread, and this year’s iPhone 5C and iPhone 5S represent a curious creative nadir for the firm. A new Windows Phone video shows how hard Apple must have worked to come up with these turds. Hint: Not that hard. ~ Paul Thurrott, Supersite for Windows, 13 September 2013

Apple’s innovation problem is real. And it’s unlikely to silence the critics if it simply unveils multi-colored iPhones on Tuesday. Rivals have caught up to Apple in the markets it once dominated, and the tech giant’s rumored future products appear to be more evolutionary than revolutionary. ~ Julianne Pepitone and Adrian Covert, CNNMoneyTech, 8 September 2013

They only have 60 days left to either come up with [an iWatch] or they will disappear. –Trip Chowdhry >[Written in April, 2014, one year before the Apple Watch became available.]

Apple lacks innovation, it copies. ~ Denise Garcia, CNBC, Thursday, 24 Mar 2016

While the more affordable products are seen as buying Apple time until its more blockbuster hardware event in September, Apple’s bigger problem is innovation. The company continues to be criticized for failing to innovate in the same way it did when Steve Jobs ran the company.

It has released just one new product category, the Apple Watch, since Tim Cook took the reins in 2011…. ~ Jennifer Booton, Apple sacrifices innovation for mistier market, Mar 23, 2016

The deeper question is whether Apple can keep its place as the North Star of the tech firmament. Can the company build the next great platform in computing, as it did the last one? Are its best days ahead of it, as Timothy D. Cook, the chief executive, insists — or is the new campus the capstone of an era of Apple dominance that we will never see again? ~ Farhad Manjoo, Apple, Set to Move to Its Spaceship, Should Try More Moonshots, May 4, 2016

Apple has always been renowned for being innovative and setting the rules for others to follow. … Ever since the Jobs’ death, Apple has repeatedly failed to truly innovate and offer something in the market, something that the users have never experienced before. ~ Ken Bock, Has Apple Inc. Lost Its Mojo After The Death Of Steve Jobs?, May 24, 2016

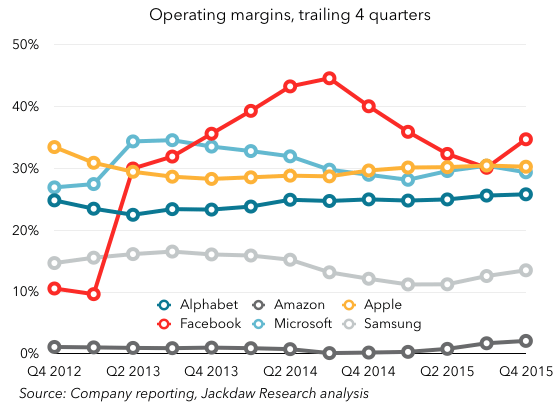

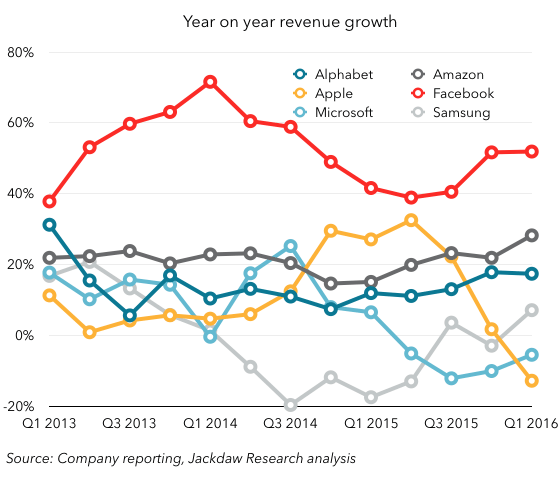

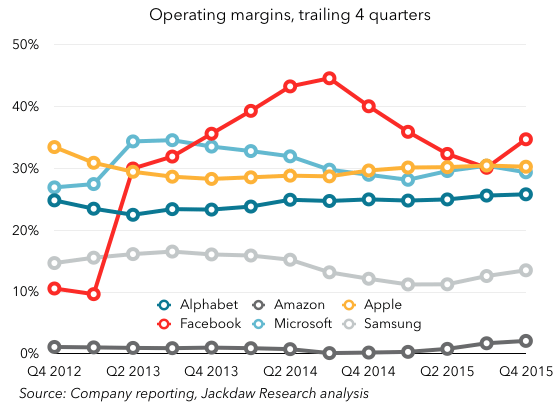

Stated simply, I don’t see any present innovation or prospective creativity at Apple. … Innovation is slowing and competitive threats are mounting. … Indeed, Facebook (FB) and Amazon (AMZN) are already challenging Apple’s position as the world’s most popular company. For many like myself, Apple is already a distant third. ~ Doug’s Daily Diary, Apple in Wonderland (April 27, 2016)

So, are the critics right? Has Apple forgotten how to innovate?

Or, is it we who have forgotten how Apple innovates?

SERIES OUTLINE

This is part 1 of 7 in a series of articles that explores Innovation at Apple.

1. Who is Apple innovating for?

2. Where should Apple’s innovation be focused?

3. How does Apple innovate?

4. When Should Apple Introduce Its Innovations?

5. What does innovation inside of Apple look like to someone outside of Apple?

6. Why does Apple do what it does?

7. Why not be Apple?

Who

Who is Apple Innovating For?

Critics seem to think Apple needs to create the next breakthrough product in order to satisfy their desires and the demands of stockholders. Let me be frank: If Apple brings out a product or service because the critics or the stockholders say they have to…then Apple is screwed.

If shareholders imagine companies exist for their benefit, they’re delirious. ~ Horace Dediu (@asymco)

It’s important to remember that the opinions of tech writers… are of no consequence to these companies. ~ @natebarham

(N)either Wall Street nor the tech press have any bearing on what matters. ~ Horace Dediu on Twitter May 16, 2016

THE CUSTOMER

Apple doesn’t do what it does for the critics or the shareholders. Apple is customer-centric. They put the customer, not the company — and certainly not the critics or the stockholders — at the center of their decision-making process. Apple bases everything on understanding their customers’ problems and what their customers might want or need in order to solve those problems.

Our DNA is as a consumer company, for that individual customer who’s voting thumbs up or thumbs down. That’s who we think about. ~ Steve Jobs

(T)he most important thing is that customers love our products and they are using them and the satisfaction has never been higher and the loyalty rates have never been higher. And that is what is really important for us. That’s the most important thing for the long term of Apple. ~ Tim Cook

As James Allworth argues in his HBR article, Steve Jobs Solved the Innovator’s Dilemma, the most profound contribution Steve Jobs made was in demonstrating a radically new way of a running a company: the goal of the firm shifts from making money for the shareholders to delighting the customer.

THE JOB TO BE DONE

Perhaps you’re thinking ‘Hey, every company is customer-centric.’ Not so. It’s not always easy to discern why buyers buy what they buy. The entire field of ‘Jobs To Be Done’ was created for the precise purpose of tackling this very thorny issue. The truth is, what seller’s sell and what buyer’s buy are, far too often, two very different things.

Examples abound. Take the Microsoft Kin, or Windows RT, or Google Glass or the Nexus Q…

…please!

It’s never easy to perfectly match what the seller sells with what the buyer buys, but a customer-centered approach — like the one Apple uses — helps to align the product design with the purchaser’s desire.

TARGET MARKET

Knowing the customer comes first is a huge part of Apple’s success. However, it is not enough to know your customer comes first. You must also first know your customer.

The technology isn’t the hard part. The hard part is…[determining] who’s the customer. ~ Steve Jobs

‘Who’s the customer?’, is a question that is not asked — and therefore is not answered — nearly enough.

APPLE’S TARGET MARKET

Let’s start with who Apple does not target. Apple does not target ‘everyone, everywhere.’

I am hearing disturbing rumours that Apple is selling a [product] that’s not right for everyone’s needs. ~ Benedict Evans @BenedictEvans

‘Everyone’ is not a target — it’s the opposite of a target. Targeting everyone is targeting no one and it’s one of the surest ways for a business to fail.

I cannot give you the formula for success, but I can give you the formula for failure–which is: Try to please everybody. ~ Herbert Bayard Swope

Apple targets only a small segment of the total market.

It is not Apple or Google’s job, or skill, to fix every vaguely Internet-related UX you’re unhappy with. Mostly they stick to their knitting ~ Benedict Evans (@BenedictEvans) 10/17/14

And that’s okay.

Today’s reminder: just because Apple makes a product that doesn’t meet your personal needs, that doesn’t make it a crappy product. ~ jcieplinski on Twitter

So, if Apple doesn’t target everyone, who do they target?

Say what you will about Apple…but it knows its market. And so do you, probably. Quick, picture an iPhone user. You’re probably picturing somebody young-ish, urban. Somebody who likes a simple user experience that doesn’t change much from model to model. Somebody who admires good industrial design, and who has the money to fit a $600-$800 phone into their budget.

Now, picture a [competitor’s] user. It’s much harder [to do]. ~ C. Custer, TechInAsia

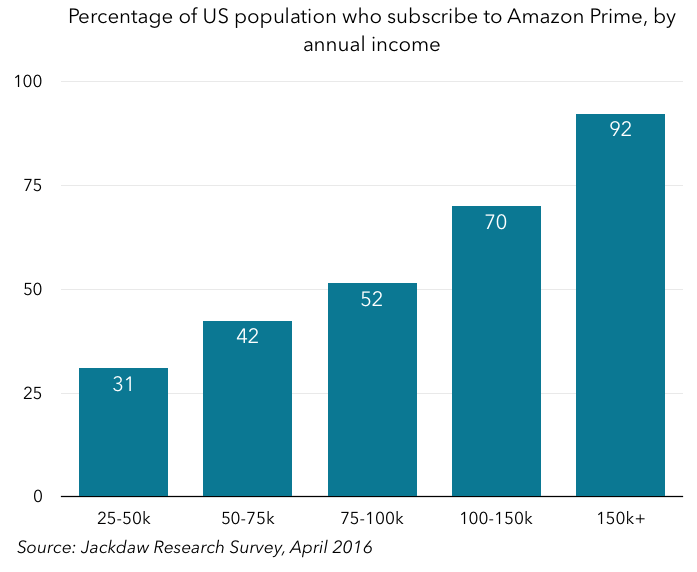

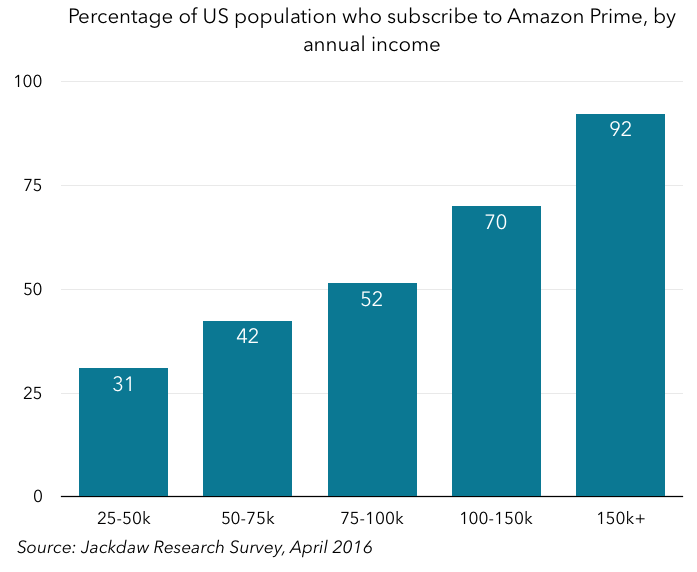

Apple targets that part of the market that buys with intent. And Apple eschews that part of the market that buys by default.

Apple targets those who value their time a little more and their money a little less; those who value raw power a little less and ease of use a little more; those who care a little more and care to pay a little more.

Has Apple been successful in attracting the customers who care?

Damn straight they have.

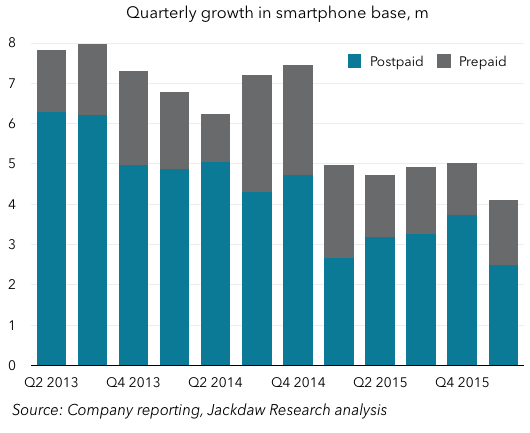

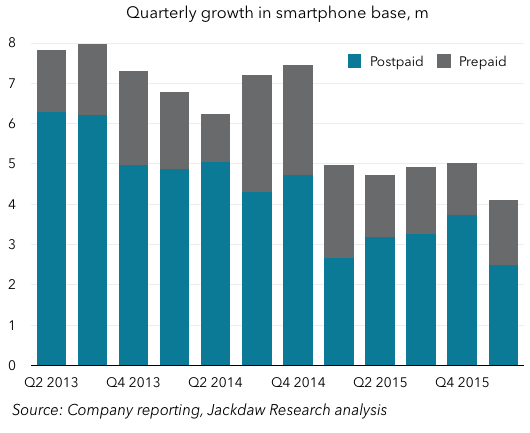

PCs mostly had people who cared but mobile has everyone, including lots of people who don’t care at all. Apple has most of those who do care. ~ Benedict Evans (@BenedictEvans) 11/29/14

The value of smartphone users is distributed on a curve and Apple has most of the best ones. This has been clear for years ~ Benedict Evans (@BenedictEvans)

Does Apple get every customer they target? Of course not. There are many people who actively choose competing products and those are precisely the prospective customers Apple seeks to acquire. Apple does not, however, seek to acquire the penny pincher or the passive purchaser.

The paradox is that it’s the open, geeky OS that’s given to non-techy late adopters & vice versa ~ Benedict Evans (@BenedictEvans)

[pullquote]Those who do not pay more to get more, pay less to get less[/pullquote]

That’s not really a paradox. That’s the way of the world. Some people are willing to pay to avoid the open, geeky OS. Some people are not. Those who do not pay more to get more, pay less to get less.

And just because there is a small, but vocal, minority who PREFER the geeky OS and who are willing to pay MORE for the geeky OS, does not make any of the above any less true.

Think of it this way. Apple runs a five star restaurant. The fact most people eat at McDonald’s does not make the proprietor of the five star restaurant ‘unpopular,’ ‘clueless,’ or — more to the point — profitless.

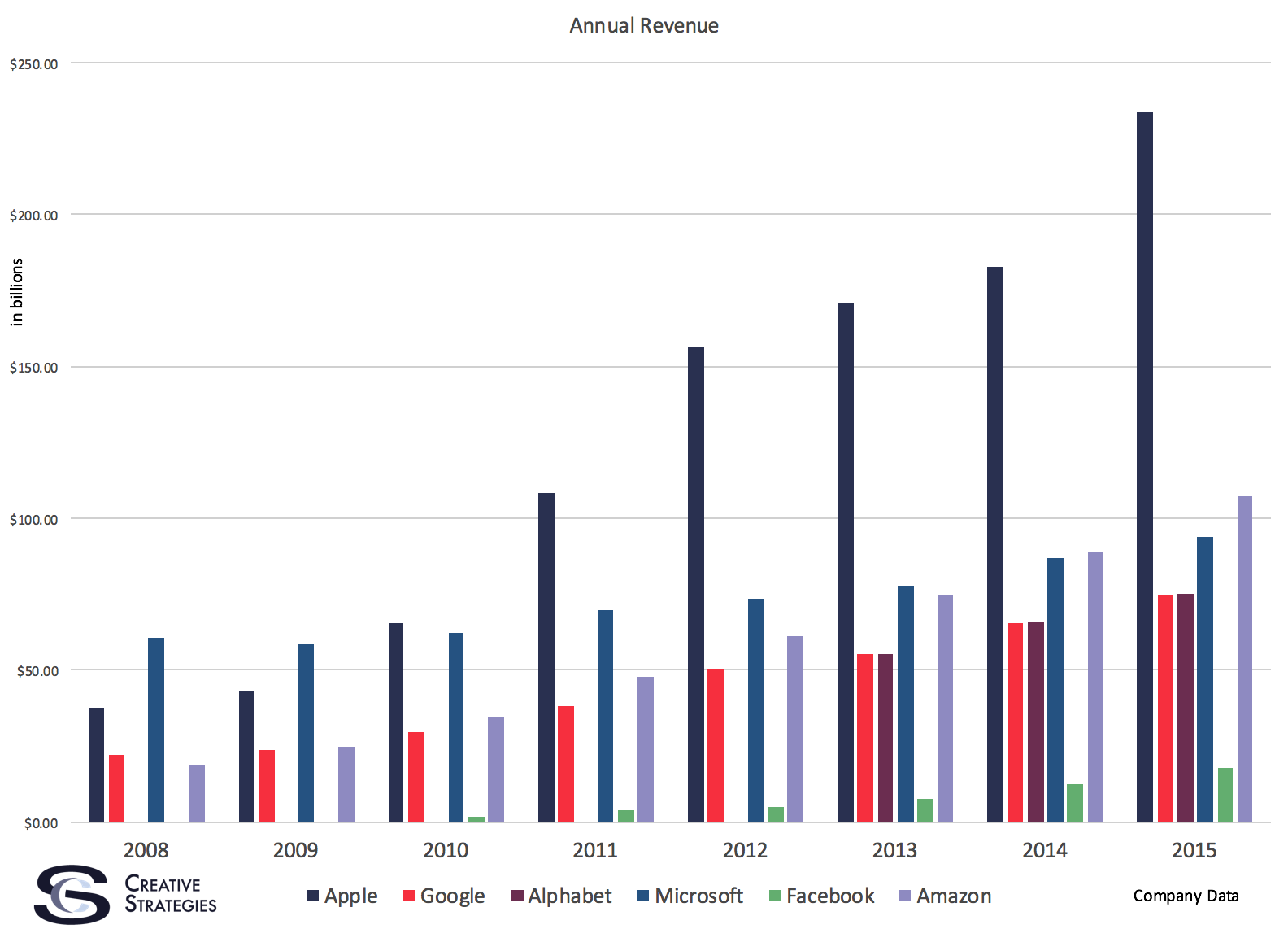

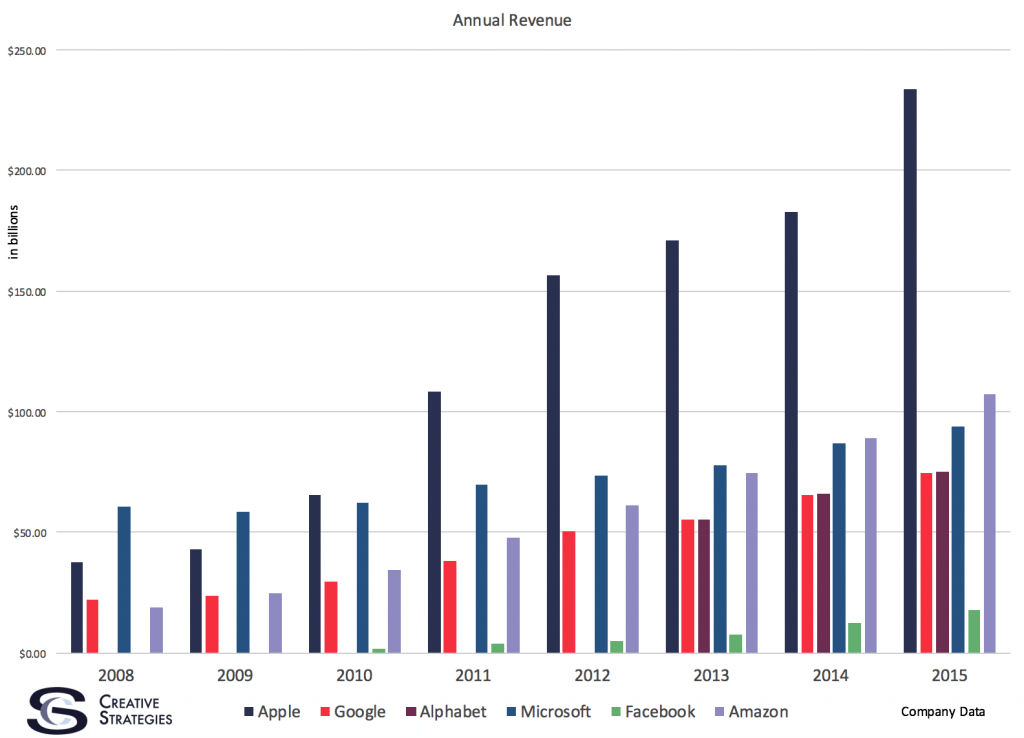

In mobile, selling a niche-high-end product turns out to make you the biggest company on earth. ~ Benedict Evans on Twitter

And the fact that many people actually PREFER the food served at McDonalds over the food served in a five star restaurant (you know who you are) does not make the patrons of the five star restaurant cultists, religious fanatics, sheep or mindless fanboys.

In [computing] as in love, we are astonished at what is chosen by others. ~ paraphrasing André Maurois

I like chez Applé, you like McAndroids. It’s all good. Eat. Enjoy.

ASPIRATIONAL

Apple’s target market is niche, yes, but it is larger than most observers realize. It is not just those who are currently interested in — and able to afford — Apple products. Apple products are aspirational. Not everyone can afford them but many desire them and will acquire them when they are able.

And we’ve found that all throughout the world, there were so many people advising us…that people weren’t going to pay for a great product there. Well, let me tell you, it’s a bunch of bull! It’s not true! People everywhere in this world want a great product. And that doesn’t mean that everyone, every single person in the world can afford one yet. But everyone wants one [emphasis added]. And so, if we do our jobs right, and keep making great products, I think there’s a pretty good business there for us. ~ Tim Cook

(T)here are a lot of people in the world who don’t have the pleasure of owning an iPhone yet. ~ Tim Cook

(I)t turns out that people in every country in the world there’s a segment of buyer that wants the best [emphasis added] product and the best experience. And that’s what we’re about providing. ~ Tim Cook

HOW APPLE MEASURES SUCCESS

The critics say Apple is off target; that they’ve missed the mark. But that’s only because the critics don’t know the mark Apple is targeting.

Once you understand WHO Apple is making their products for, you can then — and only then — begin to understand how Apple defines success and failure.

We are winning with our products in all the ways that are most important to us, in customer satisfaction, in product usage and in customer loyalty. ~ Tim Cook

Customers love our products and that is the only thing that really matters. ~ Tim Cook

If you measure success by whether Apple annually ships a new product as profitable as the iPhone — and many critics do — then Apple is one of the least successful companies — if not THE least successful company — in the world.

If, however, you measure success by customer satisfaction, product usage and customer loyalty — and Apple does — then Apple is one of the most successful companies — if not THE most successful company — in the world.

ARTICLE OUTLINE

Tomorrow, part 2 of 7.

1. Who is Apple innovating for?

2. Where should Apple’s innovation be focused?

3. How does Apple innovate?

4. When should Apple introduce its innovations?

5. What does innovation inside of Apple look like to someone outside of Apple?

6. Why does Apple do what it does?

7. Why not be Apple?