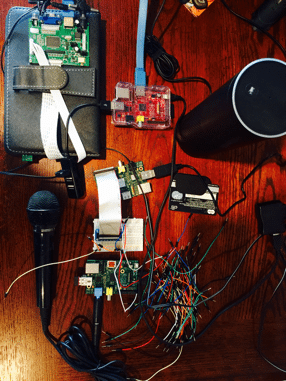

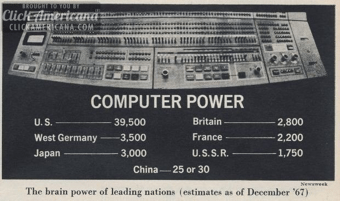

During the early computer era of the 1960s, it was thought there would only be the need for a few dozen computers. By the 1970s, there were just over 50,000 computers in the world.

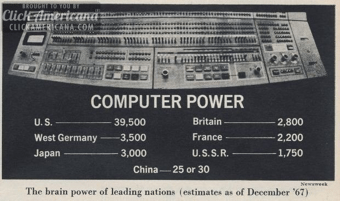

Computers have grown in power by orders of magnitude since. They have become more intelligent in the way they interact with humans, starting with switches and buttons then punch cards and on to the keyboard. Along the way, we added joysticks, the mouse, track pads and the touch screen.

Newspaper image projecting the number of computers in the world in 1967

As each paradigm replaced the last, productivity and utility. In some cases, we cling on to the prior generation’s system to such a degree we think the replacement is little more than a novelty or a toy. For example, when the punch card was the fundamental input system to computers, many computer engineers thought a direct keyboard connection to a computer was “redundant” and pointless because punch cards could move through the chute guides 10 times faster than the best typists at the time [1]. The issue is we see the future through the eyes of the prior paradigms.

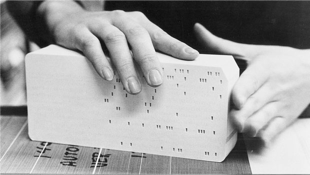

Punch card stack of customer data

We Had To Become More Like The Computer Than The Computer had to Become More Like Us

All prior computer interaction systems have one central point in common. They force humans to be more like the computer by forcing the operator to think through arcane commands and procedures. We take it for granted and forget the ground rules we all had to learn and continue to learn to use our computers and devices. I equate this to learning any arcane language that requires new vocabularies as new operating systems are released and new or updated applications are available.

Is typing and gesturing the most efficient way to interact with a computer or device for the vastly most common uses most people have? All of the cognitive (mental energy) and mechanical (physical energy) loads we must induce for even trivial daily routines is disproportionately high for what can be distilled to a yes or no answer. When seen for what it truly is, these old ways are inefficient and ineffective for many of the common things we do with devices and computers.

IBM Keypunch station to encode Punch Cards

What if we didn’t need to learn arcane commands? What if you could use the most effective and powerful communication tool ever invented? This tool evolved over millions of years and allows you to express complex ideas in very compact and data dense ways yet can be nuanced to the width of a hair [2]. What is this tool? It is our voice.

The fundamental reason humans have been reduced to tapping on keyboards made of glass is simply because the computer was not powerful enough to understand our words let alone even begin to decode our intent.

It’s been a long road to get computers to understand humans. It started in the summer of 1952 at Bell Laboratories with Audrey (Automatic Digit Recognizer), the first speaker independent voice recognition system that decoded the phone number digits spoken over a telephone for automated operator assisted calls [3].

At the Seattle World’s Fair in 1962, IBM demonstrated its “Shoebox“ machine. It could understand 16 English words and was designed to be primarily a voice calculator. In the ensuing years there were hundreds of advancements [3].

IBM Shoebox voice recognition calculator

Most of the history of speech recognition was mired in speaker dependent systems that required the user to read a very long story or grouping of words. Even with this training, accuracy was quite poor. There were many reasons for this, much of it was based on the power of the software algorithms and processor power. But in the last 10 years, there have been more advancement than in the last 50. Additionally, continuous speech recognition, where you just talk naturally, has only been refined in the last 5 years.

The Rise Of The Voice First World

Voice based interactions have three advantages over current systems:

Voice is an ambient medium rather than an intentional one (typing, clicking, etc). Visual activity requires singular focused attention (a cognitive load) while speech allows us to do something else.

Voice is descriptive rather than referential. When we speak, we describe objects in terms of their roles and attributes. Most of our interactions with computers are referential.

Voice requires more modest physical resources. Voice based interaction can be scaled down to much smaller and much cheaper form-factors than visual or manual modalities.

The power of voice-based systems has grown powerful with the addition of always-on systems combined with machine learning (Artificial Intelligence), cloud-based computing power and highly optimized algorithms.

Modern speech recognition systems have combined with almost pristine Text-to-Speech voices that so closely resemble human speech, many trained dogs will take commands from the best systems. Viv, Apple’s Siri, Google Voice, Microsoft’s Cortana, Amazon’s Echo/Alexa, Facebook’s M and a few others are the best consumer examples of the combination of Speech Recognition and Text-to-Speech products today. This concept is central to a thesis I have been working on for over 30 years. I call it “Voice First” and it is part of an 800+ page manifesto I have built based around this concept. The Amazon Echo is the first clear Voice First device.

The Voice First paradigm will allow us to eliminate many, if not all, of these steps with just a simple question. This process can be broken out to 3 basic conceptual modes of voice interface operations:

Does Things For You – Task completion:

– Multiple Criteria Vertical and Horizontal searches

– On the fly combining of multiple information sources

– Real-time editing of information based on dynamic criteria

– Integrated endpoints, like ticket purchases, etc.

Understands What You Say – Conversational intent:

– Location context

– Time context

– Task context

– Dialog context

Understands To Know You – Learns and acts on personal information:

– Who are your friends

– Where do you live

– What is your age

– What do you like

In the cloud, there is quite a bit of heavy lifting working at producing an acceptable result. This encompasses:

- Location Awareness

- Time Awareness

- Task Awareness

- Semantic Data

- Out Bound Cloud API Connections

- Task And Domain Models

- Conversational Interface

- Text To Intent

- Speech To Text

- Text To Speech

- Dialog Flow

- Access To Personal Information And Demographics

- Social Graph

- Social Data

The current generation of voice-based computers have limits on what can be accomplished because you and I have become accustomed to doing all of the mechanical work of typing, viewing, distilling, discerning and understanding. When one truly analyzes the exact results we are looking for, most can be answered by a “Yes” or “No”. When the back-end systems correctly analyze your volition and intent, countless steps of mechanical and cognitive load is eliminated. We have recently entered into an epoch where all elements converged to make the full promise of an advanced voice interface truly arrive. W. Edwards Deming [4] quantified the many steps humans need to complete to achieve any task, This was made popular by his thesis of The Shewhart Cycles and PDSA (Plan-Do-Study-Act) Cycles we have become trained to follow when using any computer or software.

The Shorter Path: “Alexa, whats’s my commute look like?”

A Voice First system would operate on the question and calculate the route from the current location to the location that may be implied by time of day and typical destination.

An app system would require you to open your device, select the appropriate app, perhaps a map, localize your current location, pinch and zoom to the destination, scan the colors or icons that represent traffic and then estimate an acceptable insight based on taking in all the information viably present and determine the arrival time.

The implicit and explicit: From Siri And Alexa To Viv

Voice First systems fundamentally change the process by decoding volition and intent using self learning artificial intelligence. The first example of this technology was with Siri [5]. Prior to Siri, systems like Nuance [6] were limited to listening to audio and creating text. Nuance’s technology has roots in optical character recognition and table arrays. The core technology of Siri was not focused just on speech recognition but rather focused primarily on three functions that complement speech recognition:

- Understanding the intent (meaning) of spoken words and generating a dialog with the user in a way that maintains context over time, similar to how people have a dialog

- Once Siri understands what the user is asking for, it reasons how to delegate requests to a dynamic community of web services, prioritizing and blending results and actions from all of them

- Siri learns over time (new words, new partner services, new domains, new user preferences, etc.)

Siri was the result of over 40 years of research funded by DARPA. Siri Inc. was a spin off of SRI Intentional and was a standalone app before Apple acquired the company in 2011 [5].

Dag Kittlaus and Adam Cheyer were cofounders of Siri Inc. and originally planned to stay on and guide their vision on a Voice First system that motivated Steve Jobs to personally start negotiations with Siri Inc.

Siri has not lived up to the grand vision originally imagined by Steve. Although improving, there has yet to be a full API and skills performed by Siri have not yet matched the abilities of the original Siri app.

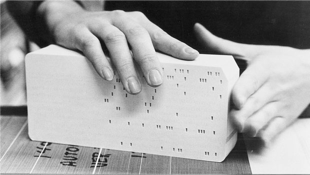

This set the stage for Amazon and the Echo product [7]. Amazon surprised just about everyone in technology when it was announced on November 6, 2014. This was an outgrowth of a Kindle e-book reader project that began in 2010 and the acquisition of voice platforms it acquired from Yap, Evi, and IVONA.

Amazon Echo circa 2015

The original premise of Echo was to be a portable book reader built around 7 powerful omni-directional microphones and a surprisingly good WiFi/Bluetooth speaker (with separate woofer and tweeter). This humble mission soon morphed into a far more robust solution that is just now taking form for most people.

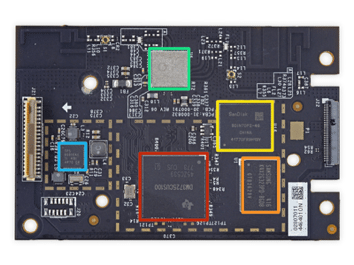

Beyond the the power of the Echo hardware is the power of Amazon Web Services (AWS) [8]. AWS is one of the largest virtual computer platforms in the world. Echo simply would not work without this platform. The electronics in Echo are not powerful enough to parse and respond to voice commands without the millions of processors AWS has at its disposal. In fact, the digital electronics in Echo are centered around 5 chips and perform little more than recording a live stream to AWS servers and sending the resulting audio stream back to be played through the analog electronics and speakers on Echo.

Amazon Echo digital electronics board

Today with a run away hit on their hands, Amazon recently opened up the system for developers with the ASK program [10]. Amazon also has APIs that connect to an array of home automation systems. Yet simple things like building a shopping list and converting it to an order on Amazon is nearly impossible to do.

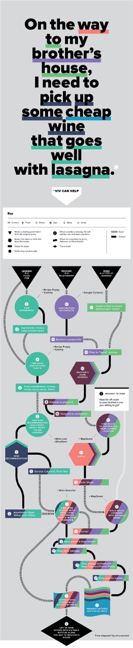

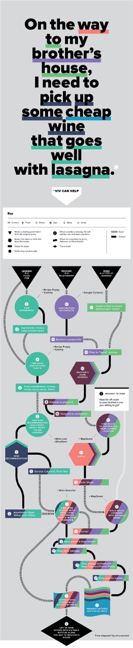

Sample of Alexa ASK skills flowchart

Echo is a step forward from the current incarnation of Siri, not so much for the sophistication of the technology or the open APIs, but for the single purpose dedicated Voice First design. This can be experienced after a few weeks of regular use. The always on, always ready low latency response creates a personality and a sense of reliance as you enter the space.

Voice First devices will span the simple to the complex to the reasonably sized to a form factor not much larger than a Lima beam.

Hypothetical Voice First device with all electronics in ear including microphone, speaker, computer, WiFi/Bluetooth and battery

The founders of Siri spent a few years thinking about the direction of Voice First software after they left Apple. The results of this thinking will begin with the first public demonstrate of Viv this spring. Viv [11] is the next generation from Dag and Adam picking up where Siri left off. Viv was developed at SixFive Labs, Inc (the stealth name of the company) with the inside “easter egg” element that the roman numerals are VI V gave a connection to the Viv name.

Viv is orders of magnitude more sophisticated in the way it will act on the dialog you create with it. The more advanced models of Ontological Recipes and self learning will make interactions with Viv more natural and intelligent. This is based upon a new paradigm the Viv team has created called “Exponential Programming”. They have filed many patents central to this concept. As Viv is used by thousand to millions of users, asking perhaps thousands of questions per second, the learning will grow exponentially in short order. Siri and the current voice platforms currently can’t do anything that coders haven’t explicitly programmed it for. Viv solves this problem with the “Dynamically Evolving Systems” architecture that operates directly on the nouns, pronouns, adjectives and verbs.

Viv flow chart example first appearing in Wired Magazine in 2015

Viv is an order of magnitude more useful than currently fashionable Chat Bots. Bots will co-exist as a subset to the more advanced and robust interactive paradigms. Many users will first be exposed to Chat Bots through the anticipated release of a complete Bot platform and Bot store by Facebook.

Viv’s power comes from how it models the lexicon of each sentence with each word in the dialog and acts on it in parallel to produce a response almost instantaneous. These responses will come in the form of a chained dialog that will allow for branching based on your answers.

Viv is built around three principles or “pillars”:

It will be taught by the world

it will know more than it is taught

it will learn something every day.

The experience with Viv will be far more fluid and interactive than any system publicly available. The results will be a system that will ultimately predict your needs and allow you to almost communicate in the shorthand dialogs found common in close relationships.

In The Voice First World, Advertising And Payments Will Not Exist As They Do Today

In the Voice First world many things change. Advertising and payments will particularly be changed and, in themselves, become new paradigms for both merchants and consumers. Advertising as we know it will not exist primarily because we would not tolerate commercial intrusions and interruptions in our dialogs. It would be equivalent to having a friend break into an advertisement about a new gasoline.

Payments will change in profound ways. Many consumer dialogs will have implicit and explicit layered Voice Payments with multiple payment type. Voice First systems will mediate and manage these situations based on a host of factors. Payments companies are not currently prepared for this tectonic shift. In fact, some notable companies are going in the opposite direction. The companies that prevail will have identified the Ontological Recipe technology to connect merchants to customers.

This new advertising and payments paradigm actually form a convergence. Voice Commerce will become the primary replacement for advertising and Voice Payments are the foundation to Voice Commerce. Ontologies [12] and taxonomies [13] will play an important part of Voice Payments. The shift will impact what we today call online, in-app and retail purchases. The least thought through of the changes is the impact on face to face retail when the consumer and the merchant interact with Voice First devices.

Of course Visa, MasterCard and American Express will play an important part of this future and all the payment companies between them and the merchant will need to rapidly change or truly be disrupted. The rate of change will be more massive and pervasive than anything that has come before.

This new advertising and payments paradigm will impact every element of how we interact with Voice First devices. Without human mediated searches on Google, there is no pay-per click. Without a scan of the headlines at your favorite news site, there is no banner advertising.

The Intelligent Agents

A major part of the Voice First paradigm is a modern Intelligent Agent (also known as Intelligent Assistant). Over time, all of us will have many, perhaps dozens, interacting with each other and acting on our behalf. These Intelligent Agents will be the “ghost in the machine” in Voice First devices. They will be dispatched independently of the fundamental software and form a secondary layer that can fluidly connect between a spectrum of services and systems.

Voice First Enhances The Keyboard And Display

Voice First devices will not eliminate display screens as they will still need to be present. However, they will be ephemeral and situational. The Voice Commerce system will present images, video and information for you to consider or evaluate on any available screen. Much like AirPlay but with locational intelligence.

There is also no doubt keyboards and touch screens will still exist. We will just use them less. Still, I predict in the next ten years, your voice is not going to navigate your device, it is going to replace your device in most cases.

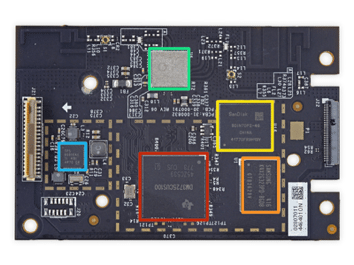

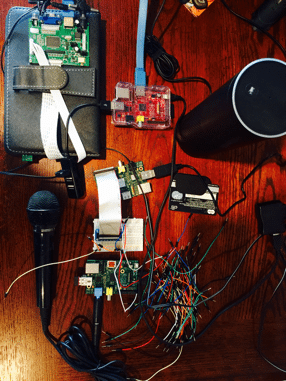

The release of Viv will influence the Voice First revolution. Software and hardware will start arriving at an accelerated rate and existing companies will be challenged by startups toiling away in garages and on kitchen tables around the world. If Apple were so inclined, with about a month’s work and a simple WiFi/Bluetooth Speaker with a multi-axis microphone extension, the current Apple TV [14] could offer a wonderful Voice First platform. In fact, I have been experimenting with this combination with great success on a food ordering system. I have also been experimenting on the Amazon Echo platform and built over 45 projects, one of which is a commercial grade hotel room service application complete with food ordering and a virtual store and mini bar along with thermostat setting and light controls for a boutique luxury hotel chain.

I am in a unique position to see the Voice First road ahead because of my years as a voice researcher and payments expert. As a coder and data scientist for the last few months, I have built 100s of simple working demos in the top portion of the Voice First use cases.

A Company You Never Heard Of May Become The Apple Of Voice First

The future of Voice First is not really an Apple vs. Amazon vs. Viv situation. The market is huge and encompasses the entire computer industry. In fact, I assert many existing hardware and software companies will have a Voice First system in the next 24 months. In addition to companies like Amazon and Viv, the first wave already have a strong cloud and AI development background. However, the next wave, like much of the Voice First shift, will likely come from companies that have not yet started or are in the early stages today.

With the Apple TV, Apple has an obvious platform for the next Voice First system. The current system is significantly hindered as it does not typically talk back in the current TV-centered use case. There is also the Apple Watch with a similar impediment of its limitation in the voice interface — it doesn’t have any ability to talk back. I can see a next version with a useable speaker but centered around a Bluetooth headset for voice playback.

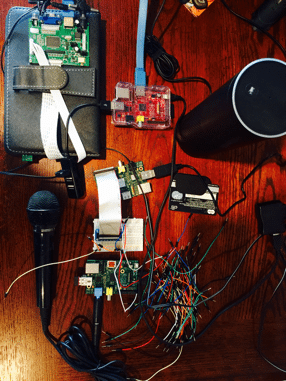

Amazon has a robust head start and has already activated the drive and creativity of the developer community. This inertia will continue and spread across non-Amazon devices. This has already started with Alexa on Raspberry PI [15], the $35 devices originally designed for students to learn to code but have now become the center of many products. Alexa is truly a Voice First system not tied to any hardware. I have developed many applications and hardware solutions using less than $30 worth of hardware on the Raspberry PI Zero platform.

One of My Raspberry PI Alexa + Echo experimentations with Voice Payments

Viv will, at the onset, be a software only product. Initially it will be accessed via apps that have licensed the technology. I also predict a deep linking into some operating systems. Ultimately if not acquired, Viv is likely to create reference grade devices that may rapidly gain popularity.

The first wave of Voice First devices will likely come from these companies with consumer grade and enterprise grade systems and devices:

- Apple

- Microsoft

- Google

- IBM

- Oracle

- Salesforce

- Samsung

- Sony

- Facebook

Emotional Interfaces

Voice is not the only element of the human experience making a comeback. In my 800 page voice manifesto I assert that emotional intent facial recognition, along with hand and body gestures, will become a critical addition to the integration of the Voice First future. Although just like voice, facial expression decoding sounds like a novelty. Our voices, combined with a decoding in real-time of the 43 muscles that form an array of expressions, can communicate not only deeper meaning but deeper understanding of volition and intent.

Microsoft Emotion API showing facial scoring

Microsoft’s Cognitive Services has a number of APIs centered around facial recognition. In particular, the Emotion API [15] is most useful. It is currently limited to a pallet of 8 basic emotions with a scoring system that allows weighting in each category in real-time. I have seen far more advanced systems in development that will track nuanced micro-movements to better understand emotional intent.

The Disappearing Computer And Device

Some argue voice systems will become an appendage to our current devices. These systems are currently present on many devices but they have failed to captivate on a mass scale. Amazon’s Echo captivates because of the dynamics present when Voice First defines a physical space. The room feels occupied by an intelligent presence. It is certain that existing devices will evolve. But it is also certain Voice First will enhance these devices and, in many cases, replace them.

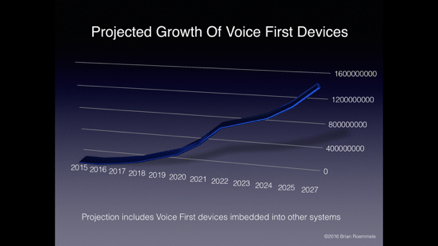

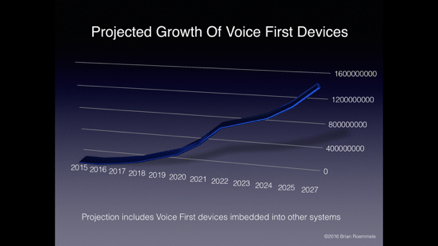

The growth of Voice First devices in 10 years will rival the growth of tablet sales

What becomes of the device, visual operating system, the app when there is little or no need to touch it? You can see just how disrupted the future is for just about every element of technology and business.

The Accelerating Rate Of Change

We have all rapidly acclimated to the accelerating rate of change this epoch has presented as exampled in the monumental shift from mechanical keyboards of cell phones, as typified by the Blackberry device of 2007 at the apex of its popularity and then shift to typing on a glass touch screen brought about with the iPhone release. All quarters, from the technological sophisticates to the common business user to the typical consumer, said they would never give up the world of the mechanical keyboard [16]. Yet, they did. By 2012, the shift had become so cemented in the direction of glass touch screens and simulated keyboards, no one was going backwards. In ten years, few will remember the tremendous amount of cognitive and mechanical steps we went through just to glean simple answers.

Typical iPhone vs. Blackberry comparisons in 2008

One Big Computer As One Big Brain

In many ways we have come full circle to the predictions made in the 1960s that there will be no need for more than a few dozen computers in the world. The huge AI self-learning systems like Viv will use the “hive mind” of the crowd. Some predict it will render our local computers little more than “dumb pipes” with a conduit to one or a few very smart computers in the cloud. We will all face the positive and the negative aspects this will bring.

In 2016, we are at the precipice of something grand and historic. Each improvement in the way we interact with computers brought about long term effects nearly impossible to calculate. Each improvement of computer interaction lowered the bar for access to a larger group. Each improvement in the way we interact with computers stripped away the priesthoods, from the 1960s computer scientists on through to today’s data science engineers. Each improvement democratized access to vast storehouses of information and potentially knowledge.

The last 60 years of computing humans were adapting to the computer. The next 60 years the computer will adapt to us. It will be our voices that will lead the way; it will be a revolution.

______

[1] http://www.columbia.edu/cu/computinghistory/fisk.pdf

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Origin_of_speech

[3] http://en.citizendium.org/wiki/Speech_Recognition

[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/W._Edwards_Deming

[5] http://qr.ae/RUWZH7

[6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nuance_Communications

[7] http://qr.ae/RUWSGC

[8] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amazon_Web_Services

[9] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amazon.com#Amazon_Prime

[10] https://developer.amazon.com/appsandservices/solutions/alexa/alexa-skills-kit

[11] http://viv.ai

[12] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ontology_%28information_science%29

[13] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taxonomy_(general)

[14] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Apple_TV

[15] https://www.microsoft.com/cognitive-services/en-us/emotion-api

[16] http://crackberry.com/top-10-reasons-why-iphone-still-no-blackberry