Whenever consumers are polled about what they want from their smartphone, the top answer is regularly “longer battery life”. That doesn’t necessarily translate into actual purchasing decisions; the number of plug-in power packs for phones is a testament to millions of people who didn’t, or couldn’t, evaluate battery life ahead of purchase or ended up pushing it down the stack of priorities when it came to buying.

A smartphone can, in essence, be boiled down to three elements: a battery, a screen and a processor. Yes, you need lots of other things too, but those are your essential building blocks.

With the release of the Samsung Galaxy S7 with Qualcomm’s new Snapdragon 820 processor, it seems like a good time to examine how the interplay of those elements shapes up. Is Apple ahead in processor design for battery life? Has the Snapdragon 820 created a new standard for the industry?

Benchmarks, benchmarks everywhere

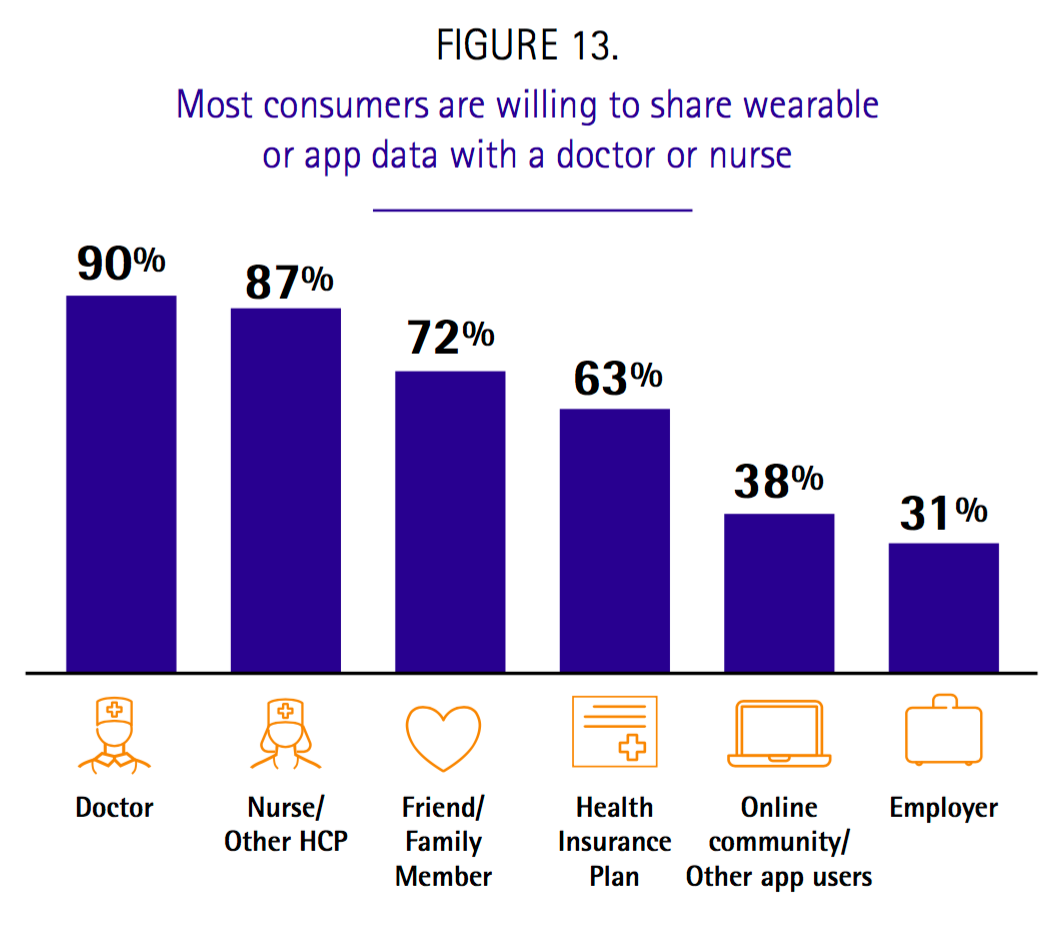

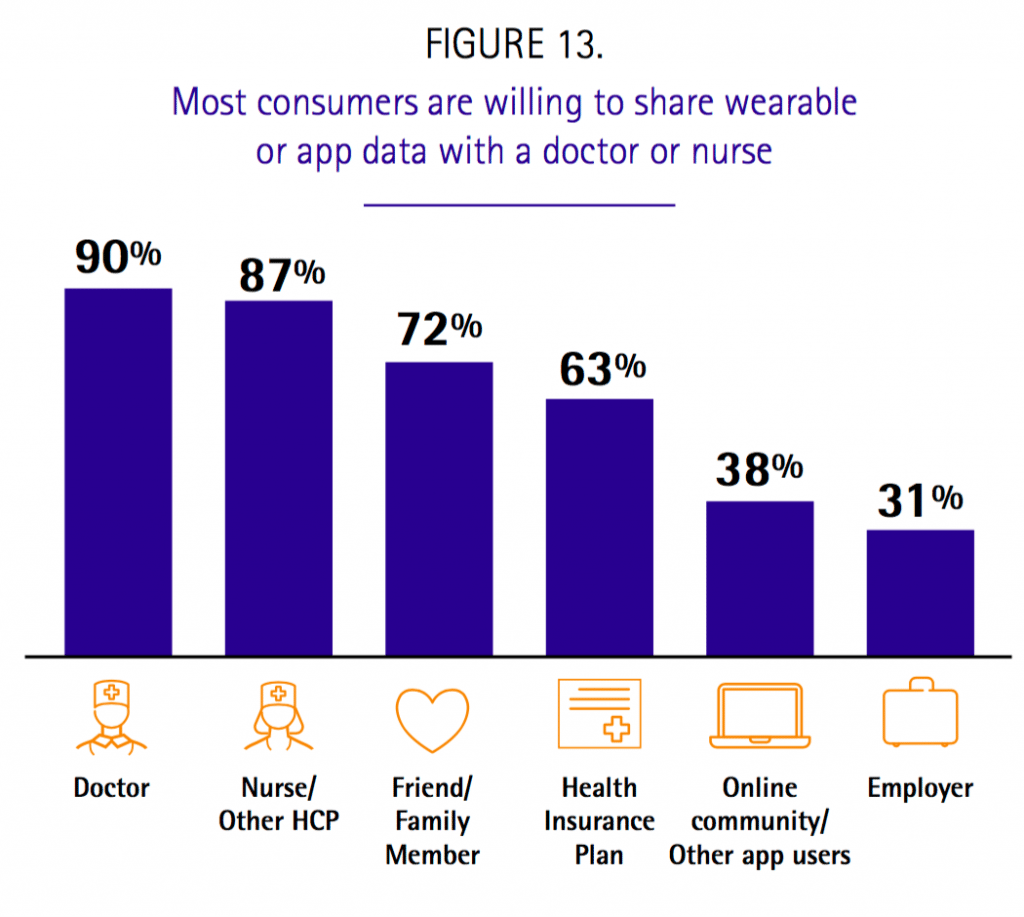

I chose to use the benchmarks on battery life from Anandtech because they cover a wide range of handsets and they perform their own standardised tests. There is a wrinkle (there always is with benchmarks): they recently changed their methodology, which has substantially reduced the apparent battery life of devices being tested. For instance, the iPhone 6S Plus life was 13.1 hours on the old benchmark, but 9.05 on the new one. The Samsung Galaxy S6 went from 10.44 hours to 7.07.

The old benchmark dated from 2013, explains Joshua Ho at Anandtech: “[it] was relatively simple in the sense that it simply loaded a web page, then started a timer to wait a certain period of time before loading the next page. And after nearly 3 years it was time for it to evolve.” (Ho also confirmed to me “13.1 hours” means 13 hours and six minutes, rather than 13 hours and 10 minutes.)

You can find a discussion of why and what they changed on Anandtech’s Samsung Galaxy 7 review section on battery life.

In the new benchmark, Ho says, “we’ve added a major scrolling component to this battery life test. The use of scrolling should add an extra element of GPU compositing, in addition to providing a CPU workload that is not purely race to sleep from a UI perspective. Unfortunately, while it would be quite interesting to also test the power impact of touch-based CPU boost, due to issues with reproducing such a test reliably we’ve elected to avoid doing such things.” He cautions, “It’s important to emphasize that these results could change in the future as much of this data is preliminary”.

Noting that, let’s go to work. The three main elements of the phone – battery, screen, processor – all affect battery life. In theory, a bigger battery, smaller chip die, and fewer pixels on the screen will all lead to longer battery life.

I collected the recorded battery capacity and screen resolution from Phonearena for a range of phones benchmarked by Anandtech and put them into a spreadsheet.

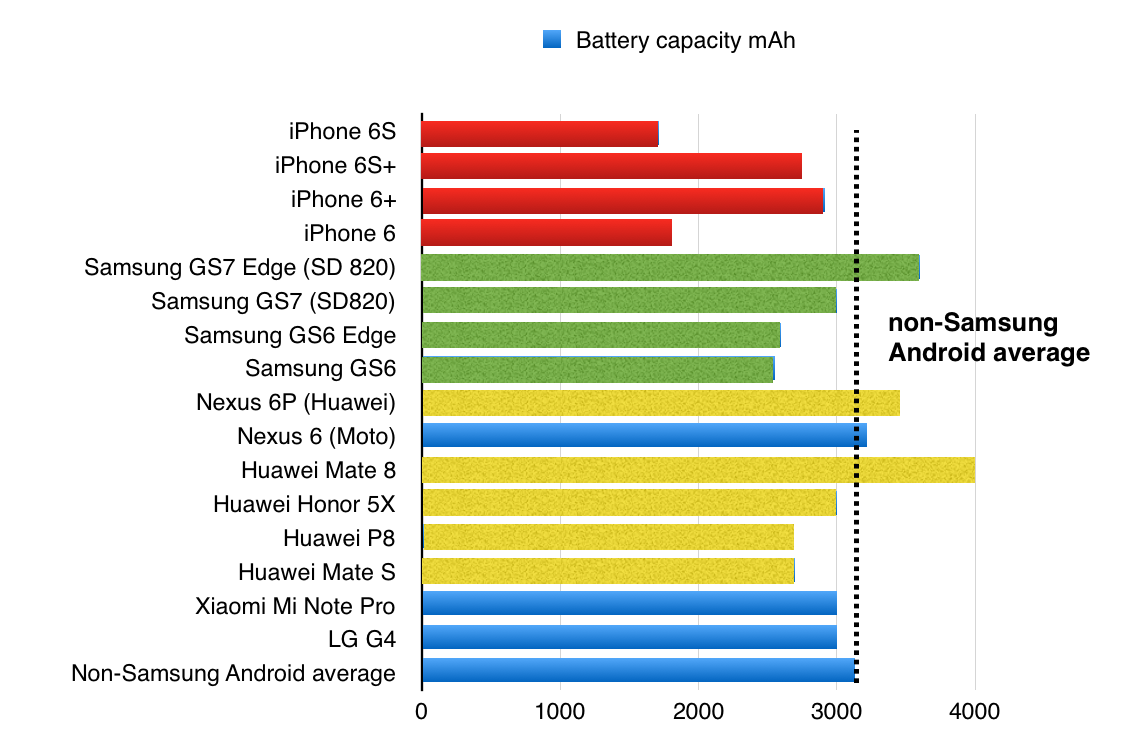

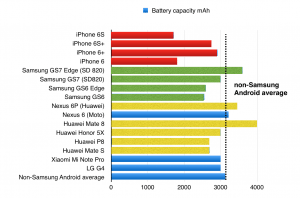

The batteries

On the face of it, Apple’s battery capacities lag behind those of Android OEMs. The figure is boosted by Huawei in particular, so the Android average here is 3,131mAh against 2,297mAh for Apple.

I’ve highlighted Apple, Samsung and Huawei because they’re the biggest players in the smartphone game. Also, those are the makers for which Anandtech has the most tests.

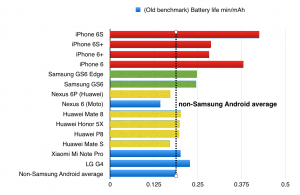

The first calculation: simple efficiency

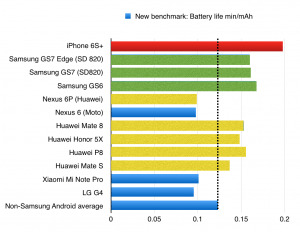

The first obvious calculation to do is: divide the battery life (minutes) by the battery capacity (milliAmphours) to get “minutes per milliamp-hour”. Doing that gives the following graphs for the old and new benchmarks:

And for the new benchmark:

In both graphs, longer is better for this particular metric.

There are a couple of obvious points here. Apple seems to do very well on “bang for buck” on the old benchmark, well ahead of any Android OEM; only Samsung did well there, on last year’s phones.

On the new benchmark, Apple still comes out some distance ahead, with Samsung a lot closer with the Galaxy S7 using the Snapdragon 820. (The S7 wasn’t tested on the old benchmark; not all of the iPhones have yet been tested against the new benchmark.) Huawei, which uses its own Kirin processor for most of its phones, also shows respectable performance – above the average for non-Samsung Androids – except, strangely, in the Nexus 6P.

The second calculation: processor efficiency at pushing pixels

There’s only one problem with the calculations above: it doesn’t take into account how many pixels the battery has to light. The phones we’re looking at there have different numbers of pixels, so lighting each one must take battery power. So now we have to do a new calculation: manipulate the above calculation to account for the number of screen pixels. In other words, if one processor gets (say) 2 minutes per mAh to light 100 pixels, but another processor gets 2 minutes per mAh to light 1000 pixels, the second processor is clearly more efficient, by a factor of 10.

To get a view of processor efficiency, we multiply the above calculation by the number of pixels on the screens.

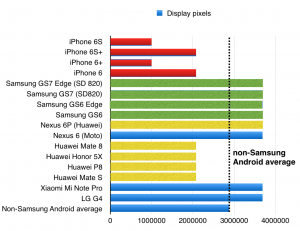

Let’s look at screen pixels:

As you can see, Apple is a long way behind most Android OEMs on this (except, notably, Huawei, and even then only for the phablet-sized Plus phones). Certainly you can argue the difference in pixel count actually makes no difference in the real world because, when held at a normal distance, the individual pixels can’t be discerned on an Apple device thus adding more to the screen makes no difference at all, except to put more load on the processor and the battery.

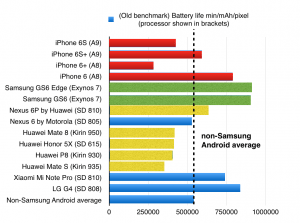

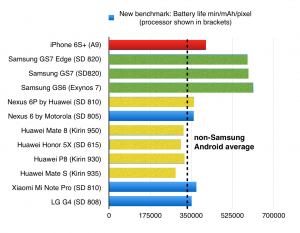

Now we’re ready to see how the processors perform when we break out battery life per pixel. This gives us some insight into processor efficiency.

Here are the results on the old Anandtech benchmark:

And the new:

As above, longer is better on this metric.

(As a reminder, Anandtech hasn’t tested every device on the new benchmark that it did for the old.)

There are quite a few points to note here. The ones that stick out to me are:

• Samsung’s Exynos processor/display efficiency leads the pack

• The Snapdragon 820 is actually a slight regression from the S6’s Exynos XXX, though apparently better than the Snapdragon 810 (which powers the Xiaomi Mi Note Pro)

• Apple’s A9 does well under the new benchmark, though it’s behind Samsung’s implementation; on the old benchmark, it’s all over the place

• Huawei’s Kirin processor lags the rest of the pack. The Nexus 6P uses the Snapdragon 810; the Kirin seems to perform about as well as a second-tier Snapdragon processor

• there are variations between manufacturers, probably down to power management and other elements. For example, the Mi Note Pro and the Nexus 6P use the same processor and have the same number of pixels (though the Nexus has a larger battery) but the Xiaomi product comes out ahead on both versions of the “efficiency” benchmark

• Samsung’s clear advantage could be due to it making the screens as well as the processors, and so having much more control of manufacturing integration.

I’m sure there are plenty more observations to be made; they’re welcomed in the comments. One thing that’s definitely worth noting is these calculations don’t take into account any usability or user experience measurements. They don’t tell you about frame rates or what the phones or screens or user interface is like. That’s a far more complex question which likely remains beyond the province of benchmarks.