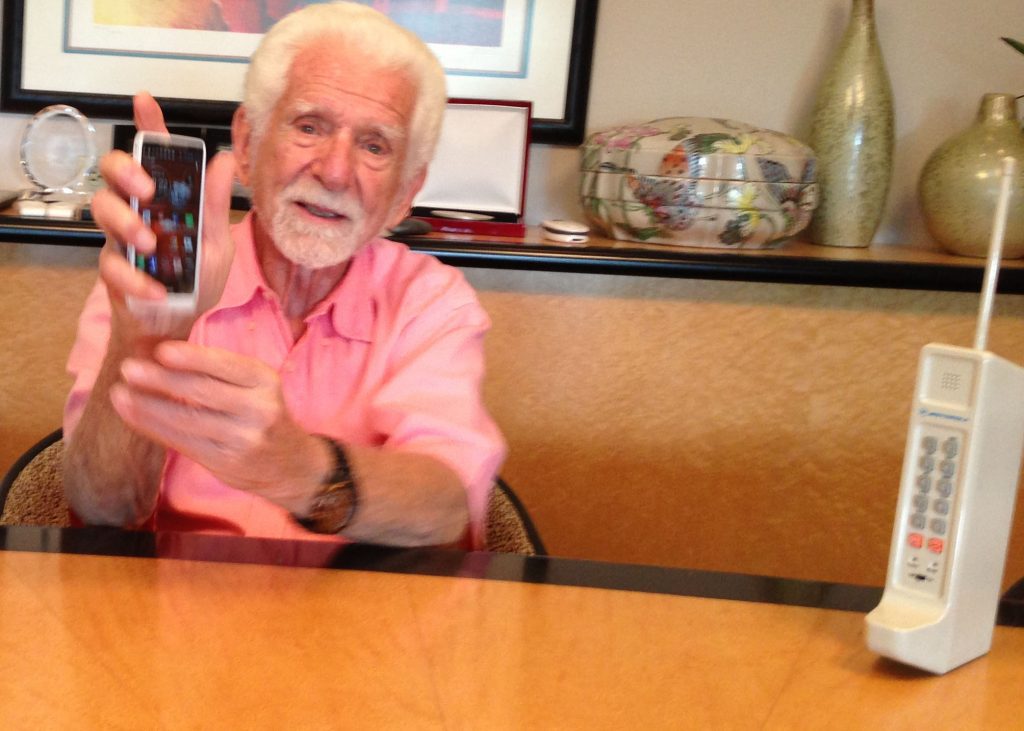

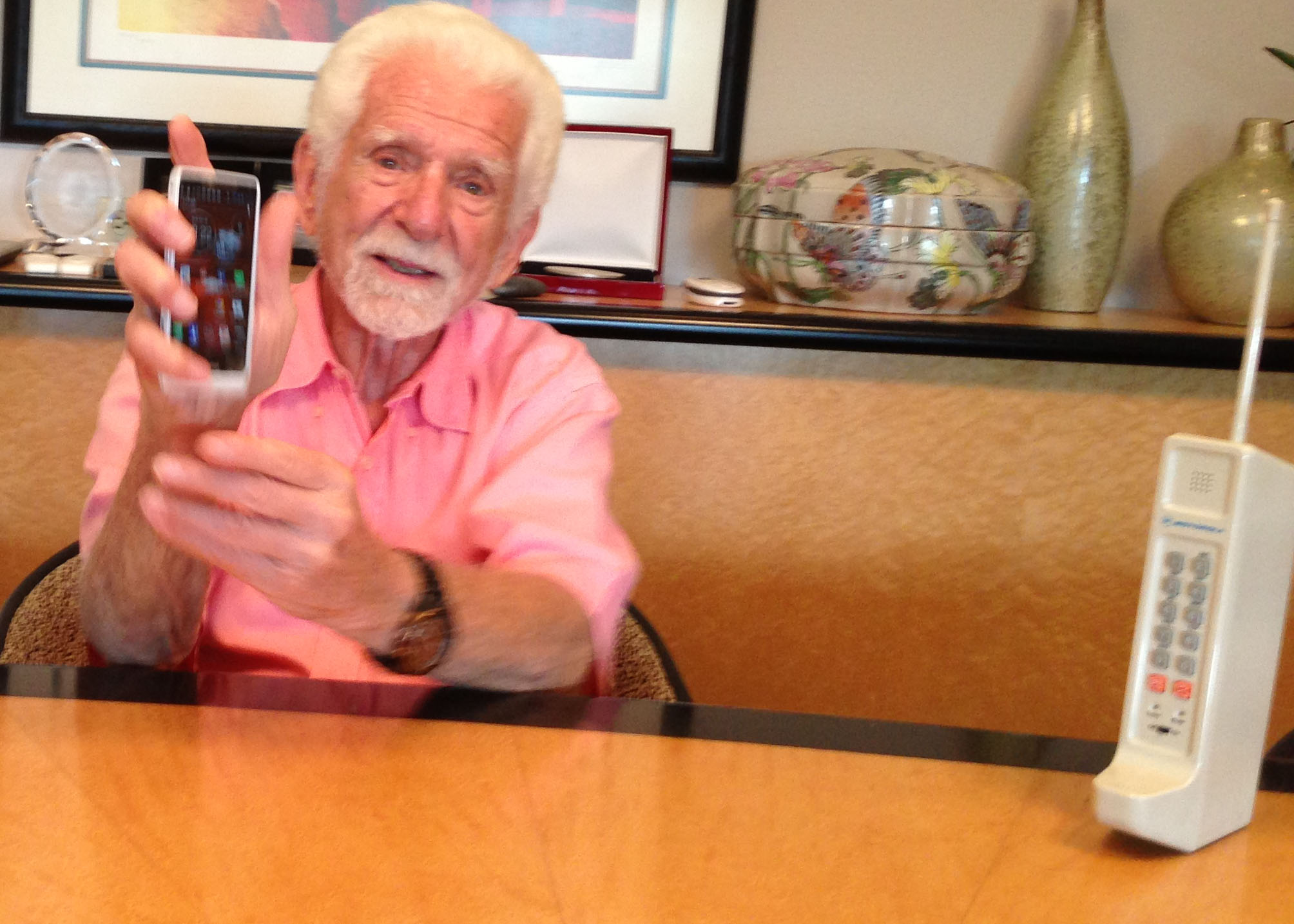

It has been almost 40 years since Martin Cooper made the mobile phone call that earned him the title of father of the cell phone. Today he is still active in the industry, looking for ways to make mobile better. Like many others, he thinks t5hat finding enough spectrum to handle soaring wireless data usage is the great challenge. Unlike many, however, he has ideas that go beyond reallocating a limited pool of wireless spectrum.

One of his concerns is that what has been spectacular growth in the efficiency of spectrum use has slowed. “There’s not much motivation for the people who have the spectrum to get more efficient,” he says. “Why should they get more efficient when all they have to do is ask for more spectrum? Yes, they have to pay for it, but the cost of spectrum at auction is the bargain of the century. Just think about it. You may spend $1 billion to get a piece of spectrum but that spectrum is going to double in value every 2½ years.”

So Cooper, who has spent many years working on smart antenna technology that would allow more effective reuse of spectrum, has an idea to create an incentive. “One possible way, and a way that I suggest would be really valuable for the government to get people to operate more efficiently, is what I call the Presidential Prize. Suppose the government offers the industry the opportunity to get, say, 10 MHz of spectrum free of charge, no auction price or anything, All you’d have to do to get that 10 MHz of spectrum is demonstrate that you could operate at least 50 times more efficiently than existing people. Well, if somebody could do that, they’d have the equivalent spectrum of 50 times 10 MHz, or 500 MHz of spectrum today.

“So my suggestion is let’s have a contest to see who can get to 50 times improvement over the next 10 years or so. It’s going to cost a lot of money to do that, but we’re going to find that we’ll have some new carriers , people that have made substantial investments, and we’ll now be using the spectrum more efficiently. The spectrum belongs to us, to the public, not to the carriers. We only lease it to the carriers, and they are supposed to operate in the public interest. It is in the public interest to use that spectrum efficiently and make it available to more and more people. The only way to do that is to get the cost down.”

You can see much more of my interview with Cooper, including video, on Cisco’s The Network.

In recent months, I have seen several accounts in

the press discussing Martin Cooper’s role in the development of the cell phone.

I worked for Martin at Motorola Communications and Industrial Electronics

(C&IE) from November 1959 to June 1960. Motorola was developing the latest

in a series of two way radio products of ever smaller size. These developments

were part of an evolutionary process that led eventually to the cell phone. I

was fresh out of school and my contributions were of no particular significance.

But let me tell you about something I observed on a

daily basis at Motorola’s plant in Chicago. Motorola C&IE had two black

employees. They tended an incinerator on the opposite side of the parking lot

from the plant. They were not allowed into the building. Not to take a break or

eat lunch. Not to use the rest rooms. Not to warm up in the middle of Chicago’s

sub zero winters. And my fellow employees would take their breaks at the second

floor windows overlooking that parking lot, and they would make insulting,

racist comments about the two black employees.

I went to human relations, and in the most

non-confrontational way that I could muster I asked why Motorola did not employ

on the basis of ability, without regard to race. And at my six month review, I

was terminated.

You don’t have to take my word concerning Motorola’s

employment policies. In September of 1980, Motorola agreed to pay up to $10

million in back pay to some 11,000 blacks who were denied jobs over a seven-year

period and to institute a $5 million affirmative action program, according to

the federal Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

I have a question for Martin Cooper. Marty, what did you

ever do to challenge the blatant, toxic racial discrimination at

Motorola?

Robert,why:

1.have you chosen to spray this 40-years old complaint all over the Internet? I have found at least 42 places where you have pasted this complaint word-for-word onto news websites that wrote an article about Dr. Cooper. Don’t you have an original idea?

2.why are you complaining to news outlets? They can’t do anything and your ont-of-date allegations are not going to cause them to suddenly cover this topic.

3. as you noted, Motorola did settle with black employees from this period that was before the landmark Civil Rights legislation of the 1960′s. These harms have been addressed and resolved, and as you know Motorola no longer behaves in this manner — like most other American corporations.

So, please — for all of us — just shut up, already!

Find something more useful to do than spraying decades-old discrimination allegations at Dr. Cooper in an attempt to sully the reputation of one of the great inventors of our time. You’re wasting everyone’s time with this useless one-man smear campaign.

Here we will explain once again what the advantages of the JAMUSLOT slot game are. for all readers to have a deeper understanding. Basically, the amount of the online slot jackpot prize depends on how many players have played it. The more players, the more prizes. That’s why we really recommend Joker for bettors in Indonesia because slot games have a lot of fans. Registering for real money online slots here is very easy. For clearer information, you can visit our website JAMUSLOT is the largest online gaming site in Asia which awards the jackpot

big every day.

Here we will explain once again what the advantages of the TRIBUNTOGEL slot game are. for all readers to have a deeper understanding. Basically, the amount of the online slot jackpot prize depends on how many players have played it. The more players, the more prizes. That’s why we really recommend Joker for bettors in Indonesia because slot games have a lot of fans. Registering for real money online slots here is very easy. For clearer information, you can visit our website TRIBUNTOGEL is the biggest online gaming site in Asia that provides jackpots

big every day.

Here we will explain once again what the advantages of the PPSOFT slot game are. for all readers to have a deeper understanding. Basically, the amount of the online slot jackpot prize depends on how many players have played it. The more players, the more prizes. That’s why we really recommend Joker for bettors in Indonesia because slot games have a lot of fans. Registering for real money online slots here is very easy. For clearer information, you can visit our website PPSOFT is the largest online gaming site in the world. Asia that gives the jackpot

big every day.

In recent months, I have seen several accounts in

the press discussing Martin Cooper’s role in the development of the cell phone.

I worked for Martin at Motorola Communications and Industrial Electronics

(C&IE) from November 1959 to June 1960. Motorola was developing the latest

in a series of two way radio products of ever smaller size. These developments

were part of an evolutionary process that led eventually to the cell phone. I

was fresh out of school and my contributions were of no particular significance.

But let me tell you about something I observed on a

daily basis at Motorola’s plant in Chicago. Motorola C&IE had two black

employees. They tended an incinerator on the opposite side of the parking lot

from the plant. They were not allowed into the building. Not to take a break or

eat lunch. Not to use the rest rooms. Not to warm up in the middle of Chicago’s

sub zero winters. And my fellow employees would take their breaks at the second

floor windows overlooking that parking lot, and they would make insulting,

racist comments about the two black employees.

I went to human relations, and in the most

non-confrontational way that I could muster I asked why Motorola did not employ

on the basis of ability, without regard to race. And at my six month review, I

was terminated.

You don’t have to take my word concerning Motorola’s

employment policies. In September of 1980, Motorola agreed to pay up to $10

million in back pay to some 11,000 blacks who were denied jobs over a seven-year

period and to institute a $5 million affirmative action program, according to

the federal Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. See the attached

PDF file for details.

I have a question for Martin Cooper. Marty, what did you

ever do to challenge the blatant, toxic racial discrimination at

Motorola?

Robert Gilchrist Huenemann, M.S.E.E.

120 Harbern Way

Hollister, CA 95023-9708

831-635-0786

bobgh@razzolink.com

https://sites.google.com/site/bobhuenemann/

Extra

Class Amateur Radio License W6RFW

Here we will explain once again what the advantages of the BOCORAN SLOT slot game are. for all readers to have a deeper understanding. Basically, the amount of the online slot jackpot prize depends on how many players have played it. The more players, the more prizes. That’s why we really recommend Joker for bettors in Indonesia because slot games have a lot of fans. Registering for real money online slots here is very easy. For clearer information, you can visit our website SLOT LEAKS which is the biggest online gaming site se Asia which provides jackpots

big every day.

Hey very nice site!! Man .. Beautiful .. Amazing .. I will bookmark your blog and take the feeds also…I am happy to find a lot of useful information here in the post, we need develop more techniques in this regard, thanks for sharing. . . . . .

very satisfying in terms of information thank you very much.

Hello! I just would like to give a huge thumbs up for the great info you have here on this post. I will be coming back to your blog for more soon.

Saved as a favorite, I really like your blog!

Hiya, I am really glad I have found this info. Today bloggers publish just about gossips and web and this is really annoying. A good website with exciting content, that’s what I need. Thank you for keeping this site, I’ll be visiting it. Do you do newsletters? Can’t find it.

I’m not sure exactly why but this site is loading incredibly slow for me. Is anyone else having this problem or is it a problem on my end? I’ll check back later and see if the problem still exists.

you’re really a good webmaster. The web site loading speed is incredible. It seems that you’re doing any unique trick. Moreover, The contents are masterpiece. you’ve done a excellent job on this topic!

Fantastic web site. Plenty of useful information here. I’m sending it to a few pals ans also sharing in delicious. And obviously, thank you in your effort!

I’ll right away seize your rss feed as I can’t find your e-mail subscription link or newsletter service. Do you’ve any? Please allow me understand so that I may subscribe. Thanks.

Glad to be one of the visitants on this awesome site : D.

I was looking at some of your blog posts on this site and I believe this web site is very instructive! Keep putting up.

At WAKTOGEL, today’s Gacor slot game is a game that can be played online. This game offers a variety of slot games. Players can place small or large bets to try their luck. Depending on how much money you are willing to spend, you can find a jackpot at any time. The website also offers various bonus packages to keep you coming back for more. WAKTOGEL is the biggest online game site in Asia that provides jackpots

I am typically to running a blog and i really appreciate your content. The article has really peaks my interest. I’m going to bookmark your website and maintain checking for new information.

whoah this blog is magnificent i love reading your posts. Keep up the great work! You know, a lot of people are looking around for this information, you can aid them greatly.

I like this blog so much, saved to bookmarks.

I am glad to be a visitant of this pure web site! , thanks for this rare information! .

I like what you guys are up too. Such intelligent work and reporting! Keep up the excellent works guys I have incorporated you guys to my blogroll. I think it’ll improve the value of my web site 🙂

You could definitely see your enthusiasm in the work you write. The world hopes for even more passionate writers like you who are not afraid to say how they believe. Always follow your heart.

Throughout this grand design of things you receive an A for effort. Where exactly you actually misplaced everybody was first in all the facts. As they say, details make or break the argument.. And that couldn’t be much more correct at this point. Having said that, permit me inform you just what exactly did work. Your authoring can be really powerful and this is possibly why I am taking the effort to opine. I do not really make it a regular habit of doing that. Second, despite the fact that I can certainly notice a leaps in reason you make, I am not necessarily convinced of how you seem to connect the details which make your conclusion. For now I will, no doubt subscribe to your issue but hope in the future you link your dots better.

I am often to blogging and i really appreciate your content. The article has really peaks my interest. I am going to bookmark your site and keep checking for new information.

Real nice design and style and wonderful subject material, nothing else we want : D.

I love your blog.. very nice colors & theme. Did you design this website yourself or did you hire someone to do it for you? Plz respond as I’m looking to design my own blog and would like to know where u got this from. thanks a lot

Hello.This post was extremely interesting, especially because I was searching for thoughts on this topic last couple of days.

you could have an ideal blog here! would you wish to make some invite posts on my blog?

Some truly superb blog posts on this web site, thankyou for contribution.

I am constantly invstigating online for tips that can help me. Thx!

I think this is among the most important information for me. And i am glad reading your article. But wanna remark on few general things, The website style is wonderful, the articles is really great : D. Good job, cheers

Hello my friend! I want to say that this article is amazing, nice written and include approximately all significant infos. I would like to peer more posts like this .

There are actually lots of particulars like that to take into consideration. That may be a great level to deliver up. I offer the thoughts above as basic inspiration however clearly there are questions just like the one you convey up where an important factor shall be working in trustworthy good faith. I don?t know if best practices have emerged round things like that, but I’m positive that your job is clearly identified as a fair game. Both girls and boys really feel the impact of only a moment’s pleasure, for the remainder of their lives.

I’ll right away clutch your rss as I can’t to find your email subscription hyperlink or e-newsletter service. Do you’ve any? Please let me understand so that I could subscribe. Thanks.

Valuable information. Fortunate me I found your web site accidentally, and I am stunned why this coincidence didn’t took place earlier! I bookmarked it.

Very efficiently written article. It will be useful to anyone who utilizes it, including myself. Keep doing what you are doing – for sure i will check out more posts.

Hello very nice website!! Man .. Excellent .. Wonderful .. I’ll bookmark your website and take the feeds also?KI am satisfied to search out numerous useful info here in the publish, we’d like work out more techniques in this regard, thanks for sharing. . . . . .

Hey! I know this is kinda off topic however , I’d figured I’d ask. Would you be interested in exchanging links or maybe guest writing a blog post or vice-versa? My site goes over a lot of the same subjects as yours and I believe we could greatly benefit from each other. If you might be interested feel free to shoot me an email. I look forward to hearing from you! Excellent blog by the way!

It’s really a great and helpful piece of information. I’m glad that you shared this helpful information with us. Please keep us informed like this. Thanks for sharing.

I found your weblog web site on google and verify just a few of your early posts. Proceed to maintain up the excellent operate. I just further up your RSS feed to my MSN News Reader. Seeking forward to reading more from you later on!…

hi!,I really like your writing so so much! share we communicate more approximately your article on AOL? I require an expert in this area to resolve my problem. Maybe that’s you! Having a look forward to look you.

Hi there! I know this is kinda off topic however , I’d figured I’d ask. Would you be interested in trading links or maybe guest authoring a blog article or vice-versa? My blog goes over a lot of the same subjects as yours and I feel we could greatly benefit from each other. If you are interested feel free to shoot me an e-mail. I look forward to hearing from you! Superb blog by the way!

Great blog here! Also your web site a lot up fast! What web host are you using? Can I get your associate link for your host? I wish my site loaded up as quickly as yours lol

Great wordpress blog here.. It’s hard to find quality writing like yours these days. I really appreciate people like you! take care

Just a smiling visitant here to share the love (:, btw outstanding design and style.

I am constantly thought about this, thankyou for putting up.

What i do not understood is if truth be told how you are not really much more smartly-liked than you may be right now. You’re so intelligent. You realize therefore considerably in relation to this topic, produced me for my part imagine it from a lot of various angles. Its like women and men are not interested until it’s something to do with Girl gaga! Your individual stuffs excellent. All the time handle it up!

I used to be very happy to find this web-site.I needed to thanks to your time for this glorious learn!! I definitely having fun with every little bit of it and I’ve you bookmarked to check out new stuff you blog post.

hi!,I like your writing very much! share we communicate more about your article on AOL? I require a specialist on this area to solve my problem. Maybe that’s you! Looking forward to see you.

F*ckin’ amazing things here. I’m very glad to see your post. Thanks a lot and i’m looking forward to contact you. Will you kindly drop me a e-mail?

Good info. Lucky me I reach on your website by accident, I bookmarked it.

Thanks for every other fantastic post. The place else could anybody get that type of information in such a perfect way of writing? I have a presentation next week, and I’m at the look for such information.

Hi my family member! I wish to say that this article is awesome, nice written and include almost all important infos. I’d like to look more posts like this.

Heya i’m for the primary time here. I came across this board and I find It really helpful & it helped me out a lot. I’m hoping to provide one thing again and help others such as you helped me.

I dugg some of you post as I cogitated they were very useful extremely helpful

Some really wonderful information, Glad I detected this. “Life is divided into the horrible and the miserable.” by Woody Allen.

I really enjoy examining on this website, it has got excellent articles. “And all the winds go sighing, For sweet things dying.” by Christina Georgina Rossetti.

As a Newbie, I am permanently browsing online for articles that can aid me. Thank you

Wonderful goods from you, man. I’ve take into account your stuff prior to and you are just extremely magnificent. I really like what you’ve got here, really like what you are stating and the way wherein you say it. You make it enjoyable and you continue to take care of to keep it smart. I can not wait to read far more from you. This is actually a great website.

In the awesome scheme of things you actually receive a B+ with regard to hard work. Where you confused us ended up being on all the facts. As they say, details make or break the argument.. And it could not be more correct here. Having said that, permit me say to you just what did work. Your text is certainly very powerful which is possibly the reason why I am making an effort to opine. I do not really make it a regular habit of doing that. 2nd, even though I can certainly notice a leaps in logic you make, I am not convinced of how you appear to connect your ideas which help to make the final result. For right now I will, no doubt yield to your position but hope in the near future you actually connect the dots much better.

When I originally commented I clicked the -Notify me when new comments are added- checkbox and now each time a comment is added I get four emails with the same comment. Is there any way you can remove me from that service? Thanks!

You have observed very interesting points! ps decent internet site.

I have read a few good stuff here. Certainly value bookmarking for revisiting. I wonder how much attempt you set to create this type of fantastic informative site.

A person essentially help to make seriously posts I would state. This is the very first time I frequented your web page and thus far? I amazed with the research you made to create this particular publish incredible. Wonderful job!

I think this is one of the most important info for me. And i’m glad reading your article. But should remark on few general things, The site style is ideal, the articles is really excellent : D. Good job, cheers

Good post. I learn one thing more difficult on totally different blogs everyday. It’ll always be stimulating to learn content material from different writers and follow a little one thing from their store. I’d desire to make use of some with the content on my blog whether or not you don’t mind. Natually I’ll give you a hyperlink on your internet blog. Thanks for sharing.

Very great post. I just stumbled upon your blog and wished to mention that I have truly loved surfing around your blog posts. In any case I will be subscribing for your rss feed and I’m hoping you write again very soon!

This is a very good tips especially to those new to blogosphere, brief and accurate information… Thanks for sharing this one. A must read article.

Wow, amazing blog layout! How long have you been blogging for? you make blogging look easy. The overall look of your site is excellent, let alone the content!

You can definitely see your enthusiasm in the paintings you write. The sector hopes for even more passionate writers like you who are not afraid to say how they believe. All the time follow your heart. “Until you’ve lost your reputation, you never realize what a burden it was.” by Margaret Mitchell.

I have been absent for some time, but now I remember why I used to love this web site. Thanks , I¦ll try and check back more often. How frequently you update your site?

Write more, thats all I have to say. Literally, it seems as though you relied on the video to make your point. You clearly know what youre talking about, why waste your intelligence on just posting videos to your site when you could be giving us something enlightening to read?

There may be noticeably a bundle to know about this. I assume you made certain good points in features also.

Wow that was odd. I just wrote an incredibly long comment but after I clicked submit my comment didn’t appear. Grrrr… well I’m not writing all that over again. Regardless, just wanted to say superb blog!

I loved as much as you will receive carried out right here. The sketch is attractive, your authored subject matter stylish. nonetheless, you command get got an nervousness over that you wish be delivering the following. unwell unquestionably come more formerly again since exactly the same nearly very often inside case you shield this increase.

I am always invstigating online for ideas that can facilitate me. Thx!

You got a very excellent website, Glad I discovered it through yahoo.

you have a great blog here! would you like to make some invite posts on my blog?

Hello! I simply would like to give a huge thumbs up for the good information you could have right here on this post. I shall be coming again to your weblog for extra soon.

https://withoutprescription.guru/# tadalafil without a doctor’s prescription

I’ve learn several excellent stuff here. Certainly worth bookmarking

for revisiting. I wonder how a lot attempt you put to make the sort of fantastic

informative site.

You should take part in a contest for top-of-the-line blogs on the web. I will recommend this web site!

naturally like your website however you have to check the spelling on several of your posts. A number of them are rife with spelling problems and I find it very bothersome to inform the reality however I will certainly come back again.

Amazing! This blog looks exactly like my old one! It’s on a completely different subject but it has pretty much the same page layout and design. Wonderful choice of colors!

Do you mind if I quote a few of your articles as long as I provide credit and sources back to your website? My blog site is in the exact same niche as yours and my visitors would definitely benefit from some of the information you present here. Please let me know if this ok with you. Thanks!

It’s a shame you don’t have a donate button! I’d definitely donate to this brilliant blog!

I guess for now i’ll settle for bookmarking and adding

your RSS feed to my Google account. I look forward to new updates and will share this

website with my Facebook group. Talk soon!

best non prescription ed pills: non prescription ed pills – viagra without a doctor prescription

http://indiapharm.guru/# online pharmacy india

where can i get cheap clomid no prescription: where can i buy generic clomid without a prescription – how to get clomid without a prescription

We’re a group of volunteers and starting a brand new scheme in our community. Your website offered us with useful info to work on. You have performed a formidable process and our entire group can be grateful to you.

I am really impressed with your writing skills and also with the structure to your weblog.

Is this a paid theme or did you customize it your self? Anyway keep

up the nice quality writing, it’s rare to look a nice weblog like this one nowadays..

This article is genuinely a good one it assists new internet people, who are wishing for

blogging.

real canadian pharmacy: Legitimate Canada Drugs – canadian pharmacy world reviews

get cheap propecia without a prescription: buying generic propecia without insurance – buying cheap propecia

We are a group of volunteers and opening a brand new scheme in our community.

Your site provided us with helpful info to work on. You have performed

a formidable job and our entire community will probably be grateful to you.

mexican pharmaceuticals online: mexico drug stores pharmacies – mexican drugstore online

Hello there! I simply want to offer you a big thumbs

up for the excellent info you have here on this post.

I am coming back to your web site for more soon.

http://canadapharm.top/# is canadian pharmacy legit

what is the best ed pill: best ed medication – natural ed remedies

http://sildenafil.win/# over the counter sildenafil

п»їkamagra cheap kamagra sildenafil oral jelly 100mg kamagra

http://edpills.monster/# cheap erectile dysfunction pills

Hello! I could have sworn I’ve been to this blog before but after browsing through some of the post I realized it’s new to me. Anyways, I’m definitely happy I found it and I’ll be book-marking and checking back frequently!

I truly love your website.. Excellent colors & theme. Did you make this website yourself?

Please reply back as I’m hoping to create my very own blog and

would like to learn where you got this from or exactly what the theme is named.

Many thanks!

medicine tadalafil tablets: tadalafil online australia – cheapest tadalafil india

Levitra 10 mg buy online Cheap Levitra online Levitra generic best price

http://levitra.icu/# Buy Levitra 20mg online

I am genuinely thankful to the holder of this site who has shared this impressive article at at

this time.

sildenafil 20mg prescription cost sildenafil tablet brand name in india sildenafil 20 mg in mexico

http://kamagra.team/# п»їkamagra

My brother recommended I might like this blog. He was once entirely right.

This post truly made my day. You can not imagine simply how much time I had spent for this info!

Thanks!

sildenafil 100mg buy online us without a prescription sildenafil 100mg price canadian pharmacy sildenafil where to buy

https://sildenafil.win/# buy sildenafil online

price comparison tadalafil: where to buy tadalafil in usa – tadalafil uk generic

I¦ve recently started a site, the information you offer on this web site has helped me tremendously. Thank you for all of your time & work.

Levitra tablet price Levitra online USA fast Levitra 20 mg for sale

https://kamagra.team/# sildenafil oral jelly 100mg kamagra

tadalafil tablet buy online: tadalafil generic price – tadalafil 2.5 mg price

It’s hard to find knowledgeable people on this topic, but you sound like you know what you’re talking about! Thanks

I am not real good with English but I come up this very easygoing to read .

http://sildenafil.win/# sildenafil 25 mg tablet price

http://amoxicillin.best/# can i buy amoxicillin over the counter in australia

zithromax capsules australia buy zithromax zithromax capsules australia

buy ciprofloxacin: buy ciprofloxacin over the counter – buy ciprofloxacin over the counter

amoxicillin price canada: purchase amoxicillin online – buy amoxicillin from canada

doxycycline cap 50mg: Buy doxycycline hyclate – doxycycline 100mg cap price

https://lisinopril.auction/# price of lisinopril 5mg

buy zithromax without prescription online zithromax z-pak generic zithromax india

best lisinopril brand: lisinopril 10 mg brand name in india – lisinopril 10 mg order online

Website: Doxycycline 100mg buy online – no prescription doxycycline

http://ciprofloxacin.men/# ciprofloxacin

order amoxicillin online amoxicillin 500mg amoxicillin 500mg

lisinopril 30 mg price: lisinopril 10 mg over the counter – lisinopril 40 mg no prescription

https://amoxicillin.best/# amoxicillin without a prescription

doxycycline hyc 100mg doxycycline india order doxycycline online canada

buying lisinopril in mexico: Lisinopril 10 mg Tablet buy online – drug lisinopril 5 mg

buy zithromax no prescription: buy zithromax – zithromax online

http://ciprofloxacin.men/# buy cipro without rx

I just could not depart your web site prior to suggesting that I actually enjoyed the standard info a person provide for your visitors? Is gonna be back often in order to check up on new posts

buy amoxicillin 250mg: amoxil for sale – purchase amoxicillin online

https://amoxicillin.best/# amoxicillin 500 mg tablet

Absolutely pent subject matter, thankyou for information .

lisinopril 20 mg india buy lisinopril online lisinopril 20 mg prices

lisinopril 20mg 37.5mg: buy lisinopril online – lisinopril 60 mg

https://indiapharmacy.site/# reputable indian online pharmacy

safe reliable canadian pharmacy: legal to buy prescription drugs from canada – canada drug pharmacy

the canadian pharmacy: safe online pharmacy – canadian valley pharmacy

reputable canadian online pharmacies Top mail order pharmacies best rated canadian pharmacy

Hello, Neat post. There is a problem with your web site in web explorer, could test thisK IE nonetheless is the marketplace leader and a huge part of people will pass over your excellent writing because of this problem.

https://mexicopharmacy.store/# medicine in mexico pharmacies

aarp recommended canadian pharmacies: Online pharmacy USA – canada pharmacy online canada pharmacies

canadian pharmacy ed medications: online meds – canadian pharmacy online no prescription needed

Marvelous, what a blog it is! This blog gives helpful data to

us, keep it up.

This is a topic that’s near to my heart… Take care!

Where are your contact details though?

Yes! Finally something about Niche Ideas That Will Get You.

This is very interesting, You are a very skilled

blogger. I’ve joined your feed and look forward to seeking more of your magnificent post.

Also, I’ve shared your website in my social

networks!

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet

789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet 789bet