Smartphones have reached an interesting point in their history. When I say this is now a mature market, I mean two separate things: first, the technology has matured to the point where devices are “good enough” and second, the market is becoming fairly saturated in developed economies. Though it is clear these two forces will have an impact, it’s not yet clear exactly what that impact will look like. However, it might be useful to look at the adoption curve for another technology which saw a rapid ascent about thirty years earlier – the CD.

CD adoption was rapid but misleading

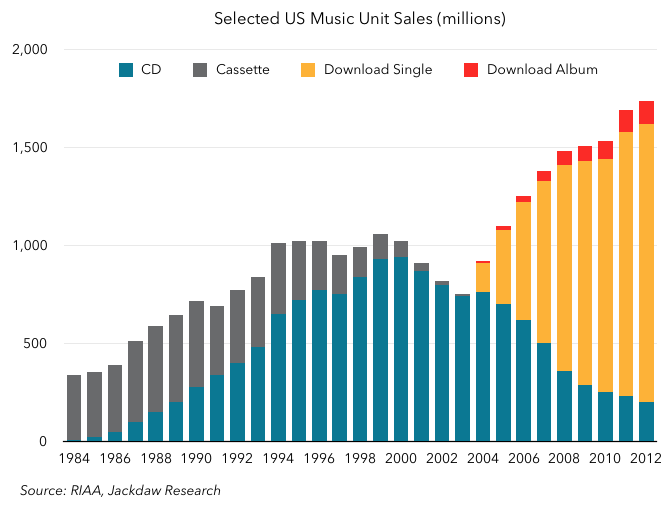

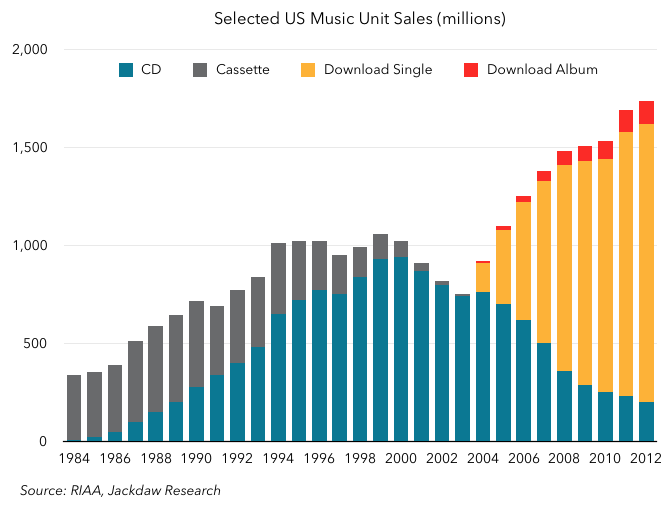

What’s interesting about CDs is growth in unit sales was very rapid from their arrival on the market but it was also misleading. The chart below shows US unit sales for various music media from 1984 to 2012, based on RIAA data. I’ve included cassette tapes, CDs (both albums and singles), and downloaded albums and singles, but not vinyl (which was in sharp decline by 1984):

Cassette sales didn’t peak until around 1990 (years after CDs first came on the market) but they peaked at around 450 million sales per year, compared with around a billion sales per year for CD albums and singles combined. Vinyl sales had earlier peaked at around 500-600 million sales per year for singles and EPs/LPs combined. CD sales were measurably higher at their peak than either of the two predecessor media. Why? I’d argue it was a combination of two things: the music industry saw a resurgence of sorts during the 1980s and 1990s, thanks to the rise of MTV and a variety of other factors, so there was some underlying growth; but secondarily, CDs sales benefited from the large number of people who upgraded their existing music collections to CD in a way they didn’t when migrating from vinyl to cassettes.

This is important because it artificially inflated expectations of how large the music industry would be going forward. I’d argue there was a bulge in sales in the 1990s caused by this media migration and lots of re-buying of the same music on a new format. Of course, the next medium to come along was digital sales and, although total unit sales were actually larger than CDs, the vast majority of those sales were of individual songs at 99 cents rather than albums at $10 or more. Why the dive in album sales? Simple – the new format was compatible in an unprecedented way with the old format – computers with CD drives could “rip” the contents of CDs and create digital files that could be played on those computers, iPods, and MP3 players. And of course, first piracy and then music downloads quickly eroded CD sales too, leaving the music industry at significantly lower revenue levels than in the peak of the CD boom.

The smartphone parallel

So far, so straightforward. But what does this have to do with smartphones? The parallels clearly aren’t perfect, but I believe there are some similarities between the two markets and their behavior which are worth drawing out. Critically, I’d argue the inflated expectations of the size of the music market that were created by the CD boom have a parallel in today’s smartphone market.

The reality is that smartphone sales each year are composed of two components: those buying their first smartphone and those upgrading from an existing device. We’ve seen very healthy smartphone sales globally for many years now and, for much of the last 15 years, we’ve seen very healthy year on year growth as well. In some ways, though, we’ve been in the CD era here and the past may well be a pretty poor predictor of the future.

What’s critical at this point is the maturity I mentioned at the outset is beginning to affect the pace of sales among both groups of smartphone buyers. In the early years of the smartphone market, first-time buyers far outweighed upgraders and were a very healthy source of growth. Lately though, this source of sales has slowed to a trickle as the vast majority of people who will ever buy a smartphone in markets like the US, Western Europe, Japan, and South Korea already have one. However, the second source of sales is also showing signs of slowing, as people hold onto their perfectly adequate phones rather than upgrading them every two years as they once did.

As this happens, we’re entering a period analogous to the early 2000s in the music industry. The major drivers of growth in the smartphone market to date have been essentially temporary in nature, Now we’re in an era characterized by dramatically slower growth, even declines. This will be particularly felt at the high end of the market, where penetration is nearer saturation on a global scale, and where the financial incentives to hold onto phones longer are that much stronger. We may well already have seen the peak for annual smartphone sales and almost certainly have for premium smartphones. That presents interesting challenges for companies like Apple or Samsung, who target the high end of the market either heavily or exclusively. As we approach Apple’s iPhone launch event next week, Apple should be thinking very hard about how to ensure existing iPhone owners see compelling reasons to upgrade and non-iPhone owners are convinced to switch.

Counterintuitively, around me Premium buyers update more than Midrange buyers, whether for fashion (need the latest) or functional (need the best) reasons. Low/mid range buyers don’t care about either I guess, and will run their phones into the ground.

That’s anecdote though, is there data either way ?

Also, I’m a bit doubtful about 2 things about the CD vs Phones analogy:

1- the analogy between media and a device. I’d even question that analogy for apps vs media, even though both are, broadly, content: I’m guessing apps remain useful and relevant and are a lot less fadish than music.

2- CDs got superseded by Downloads and then Streaming. I’m not seeing anything about to disrupt phones ?

I’m still sticking to handbags for now :-p

First, the music buying population was a lot bigger in the late 90s compared to the late 70s. At the very least you should have done a bit of math and given figures as purchases per capita.

But even more importantly, There were massive changes in the music retail and radio businesses between those two eras that made the market for vinyl in its heyday very different than the market for CDs in their heyday (speaking here, as the article does, only of the US music market). The most obvious transformation between peak vinyl and peak CD was how Indie radio stations that played a variety of music selected by individual DJs were bought out by conglomerates, and the human DJs were replaced by pre canned sets of top 40 tracks selected by a committee of suits at corporate HQ. Once all the radio stations started to sound the same, the only way to get access to new and interesting music was to buy it. So CDs became more popular than vinyl.

But the biggest mistake seems to me that you try to draw lessons about phones (a non-consumable good) from the sales history of music (a consumable good).

We buy new phones when the old ones cease to serve the purposes we expect of them (they break, don’t have a desired feature, or become displeasing/worn and ratty). We buy new media (music, video, books, magazines) because as humans we have a hunger to hear new songs and be told new stories. Re-experiencing an old song or an old story gives us pleasure, but it is of a different kind than the pleasure given by hearing a new song.

Music for sale, as opposed to performed, is an odd duck. It looks nonconsumable, but in practice it’s usually consumable with rare exceptions. Yes, we put the new music in our permanent library of songs. But after the first few listens, how often do we replay it? Usually only a tiny fraction of music purchases are truly permanent, and the rest get listened to for a while and then sit on the shelf, neglected, until it’s time to make room for new purchases by selling some of the old stuff that has lost its appeal.

Given all that, I am very dubious about this article’s foundational comparison.

I’m not sure this non-consumable vs consumable distinction you point out between phones and music is valid. The same reasoning you use to point out that music is really consumable can be modified to argue that phones are consumable too. With smartphones though, the analog to losing interest in music that one has purchased is the technology falling into obsolescence. It is obsolescence that ‘consumes’ the phone and eventually triggers the next smartphone purchase.

The comparing CDs and smartphones are actually quite valid in that both products start out with an extended bang (CDs replacing vinyl/cassette catalogs, smartphone ownership building out) that will eventually subside and level out to more stable levels.

The difference I think is that CDs were eventually superseded by downloads but I’m not sure something out there will replace smartphones (i.e. pocket sized computers) anytime soon.

Media devices became a commodity. A distribution platform for the services will become a commodity in the future. Why not luxuriously pattern/augment media for conglomerates and centigrade/VR for a conscientious public to wide the margins?

Certain consumer products, the ones that people invest their identities in such as clothes, cars, fashion accessories, bifurcate into a commoditized segment and a premium segment. So far, by all indications, smartphones fall into this category.

It’s starting to become clear what’s happening. Whether it’s Google Glass, smart watches, or driverless cars, Silicon Valley is desperately seeking some new reason to justify all of the investment dollars and bloat that it’s been swimming in, because existing hardware and software have reached saturation and are leveling off.

I think there is a major correction coming to tech, if not a crash. All of these new products have flopped. All of the low-hanging fruit of smartphones and apps has been picked clean, and at some point all of the unprofitable ventures sustained by massive investments in vapor are going to have to pay the piper.

and 640k is enough for everyone 🙂

Sure, Silicon Valley these days is running as much on the promise of devices, services, sales and profits to come as on current business. That doesn’t mean that some of it won’t actually happen, though nodoby knows which.

What’s coming, or underway, is a shakeout not a crash. As the technology matures, large-scale execution, not innovation becomes the critical skill needed for a company to survive.

You’re so awesome! I don’t believe I have read a single thing like that before. So great to find someone with some original thoughts on this topic. Really..

This post post made me think. I will write something about this on my blog. Have a nice day!!

Wonderful post! We will be linking to this great article on our site. Keep up the great writing

Hi there, I enjoy reading through your article post. I like

to write a little comment to support you.

Wonderful goods from you, man. I’ve take note your stuff prior

to and you are simply extremely great. I really like what you’ve received right here, certainly like what you’re saying

and the way in which by which you are saying it. You make it enjoyable and you still take care of

to stay it wise. I cant wait to learn much more from you. That is actually a

tremendous site.

My partner and I stumbled over here from a different website and

thought I might check things out. I like what I see so

now i’m following you. Look forward to looking into your web page

again.

I know this website presents quality dependent articles and additional

stuff, is there any other website which gives these kinds of things in quality?

Excellent post. I absolutely appreciate this website.

Keep writing!

Hey! I know this is kinda off topic but I was wondering if

you knew where I could find a captcha plugin for my comment form?

I’m using the same blog platform as yours and I’m having trouble finding one?

Thanks a lot!

Thanks for the marvelous posting! I actually enjoyed reading it, you may be a great author.I will make certain to bookmark your blog and will eventually come

back someday. I want to encourage one to continue your great work,

have a nice holiday weekend!

Ridiculous story there. What happened after? Thanks!

I have been exploring for a bit for any high-quality

articles or weblog posts in this kind of space . Exploring in Yahoo I ultimately stumbled upon this

website. Reading this information So i am glad to exhibit that I’ve an incredibly just right uncanny feeling I came

upon just what I needed. I such a lot no doubt will make certain to do not forget this

site and give it a look regularly.

I have fun with, result in I found exactly what I

was looking for. You’ve ended my four day long hunt! God Bless you man.

Have a nice day. Bye

Does your site have a contact page? I’m having trouble locating

it but, I’d like to send you an e-mail. I’ve got some ideas for your blog you might be interested in hearing.

Either way, great website and I look forward to seeing it develop over time.

I have read several good stuff here. Certainly value bookmarking for revisiting.

I wonder how much effort you set to make this sort of magnificent informative website.

It’s an remarkable article in support of all the internet

visitors; they will obtain advantage from it I am sure.

What’s up, I wish for to subscribe for this website to take newest updates, thus where can i do it

please help.

I like the valuable info you supply to your articles. I’ll bookmark your weblog and take

a look at once more right here regularly.

I am relatively sure I’ll be informed a lot of new stuff proper right here!

Good luck for the next!

Keep on writing, great job!

Terrific post however I was wanting to know if you could write a litte more on this topic?

I’d be very grateful if you could elaborate

a little bit further. Appreciate it!

I all the time used to read article in news papers but now as I am a user of internet so

from now I am using net for posts, thanks to web.

Thanks for the good writeup. It in fact was a entertainment account it.

Glance complex to far added agreeable from you!

However, how can we keep in touch?

We absolutely love your blog and find nearly all

of your post’s to be precisely what I’m looking for.

Does one offer guest writers to write content in your case?

I wouldn’t mind writing a post or elaborating on a number of the subjects you write regarding here.

Again, awesome site!

It’s not my first time to pay a visit this website,

i am browsing this website dailly and get fastidious information from here daily.

If you wish for to obtain much from this article then you have to apply such strategies to your won weblog.

I’m more than happy to uncover this web site. I want

to to thank you for your time for this fantastic read!!

I definitely loved every little bit of it and i also have you book marked to look at new things in your site.

Marvelous, what a web site it is! This weblog presents valuable facts to us,

keep it up.

What’s up, its nice paragraph regarding media print, we all be aware of media is a fantastic source of data.

Howdy great website! Does running a blog similar to this require a lot of

work? I’ve very little expertise in coding however I had been hoping to start my

own blog in the near future. Anyways, should

you have any recommendations or tips for new blog owners please share.

I know this is off subject however I simply needed to

ask. Kudos!

An outstanding share! I’ve just forwarded this onto a coworker who has been conducting

a little homework on this. And he actually ordered

me dinner because I discovered it for him… lol. So allow me to reword this….

Thanks for the meal!! But yeah, thanks for spending time to

discuss this issue here on your web site.

Wow that was strange. I just wrote an really long comment

but after I clicked submit my comment didn’t appear. Grrrr…

well I’m not writing all that over again. Regardless, just wanted to say excellent blog!

Hey there! I just wanted to ask if you ever have any problems with hackers?

My last blog (wordpress) was hacked and I ended up losing a few months of

hard work due to no data backup. Do you have any methods to protect

against hackers?

I have been surfing online greater than three hours nowadays, but

I by no means discovered any attention-grabbing article like yours.

It is pretty worth enough for me. In my opinion, if all web owners and bloggers made excellent content material

as you did, the net will probably be a lot more useful

than ever before.

Hello there! Do you use Twitter? I’d like to follow you if that

would be ok. I’m absolutely enjoying your blog and look forward to new updates.

Hello to every one, it’s truly a good for me to pay a quick visit this site, it consists

of helpful Information.

When I originally commented I clicked the “Notify me when new comments are added” checkbox and now each

time a comment is added I get three e-mails with the same comment.

Is there any way you can remove people from that service?

Cheers!

What’s up it’s me, I am also visiting this web page on a regular

basis, this web site is actually pleasant and the visitors are truly sharing nice thoughts.

Quality posts is the crucial to be a focus for the users to pay a visit the web site,

that’s what this website is providing.

hi!,I love your writing very a lot! proportion we keep in touch more about your

post on AOL? I need an expert in this area to resolve my problem.

May be that’s you! Looking ahead to see you.

Yesterday, while I was at work, my cousin stole my iPad and tested to

see if it can survive a 40 foot drop, just so she can be

a youtube sensation. My iPad is now broken and she has 83 views.

I know this is totally off topic but I had to share it with someone!

I must thank you for the efforts you’ve put in penning

this website. I’m hoping to check out the same high-grade blog

posts by you in the future as well. In truth, your creative writing abilities has motivated me

to get my very own site now 😉

Magnificent beat ! I wish to apprentice while you amend your web site,

how could i subscribe for a blog web site? The account aided

me a acceptable deal. I had been tiny bit acquainted of this your broadcast

provided bright clear idea

I like the valuable information you provide in your articles.

I’ll bookmark your weblog and check again here regularly.

I am quite certain I’ll learn lots of new stuff right here!

Good luck for the next!

Somebody essentially assist to make seriously articles I’d state.

This is the first time I frequented your website

page and to this point? I amazed with the research you

made to create this particular publish amazing. Magnificent

process!

I am really loving the theme/design of your web

site. Do you ever run into any web browser compatibility problems?

A small number of my blog readers have complained about

my website not operating correctly in Explorer but looks great in Chrome.

Do you have any advice to help fix this issue?

My partner and I stumbled over here different web address and

thought I might check things out. I like what I see so

i am just following you. Look forward to checking out your web page repeatedly.

Great work! That is the kind of information that are meant to be shared across the web.

Disgrace on Google for not positioning this put up higher!

Come on over and seek advice from my web site .

Thank you =)

First of all I want to say wonderful blog!

I had a quick question that I’d like to ask if you don’t mind.

I was interested to know how you center yourself and clear your

thoughts prior to writing. I have had a hard time clearing my mind in getting my ideas out.

I do take pleasure in writing but it just seems like the first 10

to 15 minutes tend to be wasted simply just trying to figure out how

to begin. Any ideas or hints? Many thanks!

Inspiring story there. What happened after? Good luck!

Today, while I was at work, my sister stole my iphone and tested to see if it can survive a 40

foot drop, just so she can be a youtube sensation.

My iPad is now broken and she has 83 views. I know this is totally off topic but I had to

share it with someone!

Wow, that’s what I was exploring for, what a data! existing

here at this website, thanks admin of this web site.

I am curious to find out what blog platform you have been utilizing?

I’m experiencing some minor security problems with my latest

blog and I’d like to find something more risk-free. Do you have any solutions?

It’s going to be finish of mine day, however before end I am reading this

enormous article to improve my experience.

Normally I do not read post on blogs, however I wish to say that

this write-up very forced me to try and do it! Your writing style has

been surprised me. Thanks, quite nice article.

I’m truly enjoying the design and layout of your website.

It’s a very easy on the eyes which makes it much

more pleasant for me to come here and visit more often. Did you hire

out a developer to create your theme? Outstanding work!

Hey! Someone in my Facebook group shared this site with us

so I came to check it out. I’m definitely loving the information. I’m book-marking and will be

tweeting this to my followers! Superb blog and excellent design and style.

I all the time emailed this webpage post page

to all my contacts, since if like to read it then my

contacts will too.

naturally like your website but you have to check the spelling on quite a

few of your posts. A number of them are rife with spelling issues and I in finding it very bothersome to tell the reality on the other hand I’ll definitely come

back again.

Thank you a lot for sharing this with all people

you really realize what you’re speaking approximately!

Bookmarked. Please additionally visit my site =).

We may have a hyperlink trade agreement among

us

Hi, the whole thing is going well here and ofcourse every one is sharing data, that’s in fact

fine, keep up writing.

I every time spent my half an hour to read this web site’s articles or reviews every day along

with a cup of coffee.

Hey, I think your blog might be having browser compatibility issues.

When I look at your website in Opera, it looks fine but when opening in Internet Explorer,

it has some overlapping. I just wanted to give you a quick heads up!

Other then that, superb blog!

Hi, I think your site might be having browser compatibility issues.

When I look at your website in Firefox, it looks fine but when opening in Internet Explorer, it has some overlapping.

I just wanted to give you a quick heads up!

Other then that, amazing blog!

Awesome site you have here but I was curious about if you knew of any community forums

that cover the same topics talked about in this article?

I’d really love to be a part of online community where I can get comments from other experienced people

that share the same interest. If you have any recommendations, please

let me know. Kudos!

I know this if off topic but I’m looking into starting my

own blog and was curious what all is needed to get set up?

I’m assuming having a blog like yours would cost a pretty penny?

I’m not very web savvy so I’m not 100% sure.

Any tips or advice would be greatly appreciated.

Many thanks

It’s the best time to make some plans for the long run and it’s time to be happy.

I have learn this publish and if I could I want to counsel you few fascinating issues or advice.

Perhaps you can write subsequent articles relating to this article.

I wish to learn more things about it!

I used to be able to find good info from your blog posts.

Having read this I thought it was really informative.

I appreciate you taking the time and effort to put this short article together.

I once again find myself personally spending a lot of time both

reading and posting comments. But so what, it was still worth it!

Great delivery. Outstanding arguments. Keep up the great spirit.

Great article! We are linking to this great article on our website.

Keep up the great writing.

I am actually pleased to read this webpage posts which consists of tons of helpful information, thanks

for providing such statistics.

Admiring the dedication you put into your site and

detailed information you provide. It’s nice to come across a

blog every once in a while that isn’t the same old rehashed material.

Excellent read! I’ve saved your site and I’m including your RSS feeds to my Google account.

After looking over a few of the articles on your blog, I truly appreciate your way of writing a blog.

I bookmarked it to my bookmark website list and will be

checking back in the near future. Please check out my web site as well and tell me

what you think.

I visited various web pages except the audio feature for audio songs

present at this web site is in fact marvelous.

An impressive share! I have just forwarded this onto

a friend who had been conducting a little research on this.

And he in fact bought me lunch simply because I found it

for him… lol. So let me reword this…. Thank YOU for

the meal!! But yeah, thanks for spending some time to discuss this subject here on your internet site.

certainly like your website however you need to test the

spelling on quite a few of your posts. A number of them are rife with spelling problems

and I in finding it very troublesome to tell the truth on the other hand I’ll certainly come back again.

each time i used to read smaller content which also clear their motive, and that is also happening with this post which I am reading now.

What’s up, just wanted to mention, I loved this article.

It was inspiring. Keep on posting!

Woah! I’m really enjoying the template/theme of this site.

It’s simple, yet effective. A lot of times it’s

very hard to get that “perfect balance” between superb

usability and visual appearance. I must say you have done a excellent job with this.

In addition, the blog loads extremely quick for me on Opera.

Excellent Blog!

I was recommended this website by my cousin.

I’m not sure whether this post is written by him as no one

else know such detailed about my trouble. You are wonderful!

Thanks!

My brother suggested I might like this blog. He used to

be totally right. This submit actually made my day.

You cann’t consider just how much time I had spent for this

info! Thank you!

Aw, this was a very good post. Taking the time and actual effort to generate a really good article…

but what can I say… I hesitate a lot and don’t manage to get anything done.

Hey there just wanted to give you a quick heads up. The text in your

post seem to be running off the screen in Opera. I’m not sure if this is a formatting issue or

something to do with web browser compatibility

but I figured I’d post to let you know. The layout look great though!

Hope you get the issue resolved soon. Thanks

My family always say that I am wasting my time here at web, except I know I am getting familiarity all the time by reading thes fastidious posts.

http://indianpharmacy.shop/# best online pharmacy india

cheapest online pharmacy india

reputable mexican pharmacies online: online mexican pharmacy – purple pharmacy mexico price list

http://mexicanpharmacy.win/# mexico drug stores pharmacies mexicanpharmacy.win

pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa Medicines Mexico best online pharmacies in mexico mexicanpharmacy.win

My partner and I absolutely love your blog and find the majority of your post’s to be

just what I’m looking for. Would you offer guest writers to write content to suit your needs?

I wouldn’t mind producing a post or elaborating on a few of the

subjects you write with regards to here. Again, awesome web site!

http://canadianpharmacy.pro/# canadian drug canadianpharmacy.pro

https://canadianpharmacy.pro/# canadian online pharmacy canadianpharmacy.pro

https://mexicanpharmacy.win/# mexican mail order pharmacies mexicanpharmacy.win

http://indianpharmacy.shop/# indian pharmacy online indianpharmacy.shop

http://mexicanpharmacy.win/# mexico pharmacies prescription drugs mexicanpharmacy.win

https://pharmadoc.pro/# Pharmacie en ligne France

https://levitrasansordonnance.pro/# Pharmacie en ligne sans ordonnance

Pharmacie en ligne fiable

http://acheterkamagra.pro/# Pharmacies en ligne certifiées

Pharmacie en ligne livraison 24h: acheterkamagra.pro – Acheter mГ©dicaments sans ordonnance sur internet

https://viagrasansordonnance.pro/# Viagra sans ordonnance pharmacie France

https://acheterkamagra.pro/# pharmacie en ligne

Pharmacie en ligne livraison gratuite Acheter Cialis 20 mg pas cher pharmacie ouverte 24/24

https://levitrasansordonnance.pro/# Pharmacie en ligne pas cher

https://pharmadoc.pro/# Pharmacie en ligne fiable

can i get cheap clomid without prescription: can i order clomid online – where to buy generic clomid without insurance

https://ivermectin.store/# stromectol 3 mg tablet

can you buy generic clomid pill: where to get cheap clomid prices – where can i get cheap clomid

can i buy cheap clomid where can i get clomid tablets where can i buy generic clomid now

http://azithromycin.bid/# buy zithromax 500mg online

http://clomiphene.icu/# can you buy generic clomid pills

buy oral ivermectin: ivermectin 2ml – generic ivermectin for humans

http://azithromycin.bid/# buy azithromycin zithromax

http://ivermectin.store/# ivermectin gel

buy amoxicillin 500mg uk: purchase amoxicillin online without prescription – amoxicillin 500 mg without prescription

http://clomiphene.icu/# can you buy cheap clomid without rx

http://ivermectin.store/# ivermectin iv

where to buy generic clomid now can i buy generic clomid without rx order generic clomid

where to buy cheap clomid tablets: where can i buy cheap clomid price – where can i buy cheap clomid pill

http://prednisonetablets.shop/# online order prednisone

can we buy amoxcillin 500mg on ebay without prescription: amoxicillin 500 mg for sale – buy amoxicillin over the counter uk

https://prednisonetablets.shop/# can you buy prednisone over the counter in mexico

how much is prednisone 10 mg: prednisone 60 mg – can you buy prednisone over the counter in mexico

medicine in mexico pharmacies Online Pharmacies in Mexico buying from online mexican pharmacy mexicanpharm.shop

buying prescription drugs in mexico: Certified Pharmacy from Mexico – mexican drugstore online mexicanpharm.shop

http://mexicanpharm.shop/# buying from online mexican pharmacy mexicanpharm.shop

canadian pharmacy online Best Canadian online pharmacy vipps canadian pharmacy canadianpharm.store

canadian pharmacy service: Best Canadian online pharmacy – canadian pharmacies online canadianpharm.store

https://mexicanpharm.shop/# mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa mexicanpharm.shop

mexican rx online Online Mexican pharmacy buying prescription drugs in mexico mexicanpharm.shop

https://canadianpharm.store/# reliable canadian pharmacy reviews canadianpharm.store

indian pharmacy online: india pharmacy – buy medicines online in india indianpharm.store

https://canadianpharm.store/# cheap canadian pharmacy online canadianpharm.store

canadian drugs pharmacy: Canada Pharmacy online – canadian king pharmacy canadianpharm.store

http://indianpharm.store/# indian pharmacies safe indianpharm.store

legit canadian pharmacy Canada Pharmacy online canadian pharmacy prices canadianpharm.store

https://mexicanpharm.shop/# medication from mexico pharmacy mexicanpharm.shop

best online pharmacy india cheapest online pharmacy india best online pharmacy india indianpharm.store

http://mexicanpharm.shop/# reputable mexican pharmacies online mexicanpharm.shop

online canadian pharmacy reviews: Best Canadian online pharmacy – canadian pharmacies that deliver to the us canadianpharm.store

rate canadian pharmacies: Canadian Pharmacy – canadianpharmacyworld com canadianpharm.store

https://indianpharm.store/# online shopping pharmacy india indianpharm.store

mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs п»їbest mexican online pharmacies mexican rx online mexicanpharm.shop

http://mexicanpharm.shop/# mexico pharmacies prescription drugs mexicanpharm.shop

canadian pharmacy prices Best Canadian online pharmacy online canadian pharmacy canadianpharm.store

buying prescription drugs in mexico: Online Pharmacies in Mexico – reputable mexican pharmacies online mexicanpharm.shop

https://mexicanpharm.shop/# medication from mexico pharmacy mexicanpharm.shop

п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india: top 10 online pharmacy in india – reputable indian pharmacies indianpharm.store

https://mexicanpharm.shop/# buying from online mexican pharmacy mexicanpharm.shop

http://canadianpharm.store/# canadian neighbor pharmacy canadianpharm.store

mexican rx online: Online Pharmacies in Mexico – buying from online mexican pharmacy mexicanpharm.shop

buy medicines online in india international medicine delivery from india indian pharmacies safe indianpharm.store

top online pharmacy india: reputable indian pharmacies – top online pharmacy india indianpharm.store

Please tell me more about your excellent articles

indian pharmacy online Indian pharmacy to USA online shopping pharmacy india indianpharm.store

https://mexicanpharm.shop/# mexico pharmacy mexicanpharm.shop

pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa: Online Pharmacies in Mexico – pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa mexicanpharm.shop

Hey! This is my first visit to your blog! We are a group of volunteers and starting a

new project in a community in the same niche.

Your blog provided us beneficial information to work on. You have done a outstanding job!

nabp canadian pharmacy canadian pharmaceuticals for usa sales cheapest drug prices

http://canadadrugs.pro/# my canadian pharmacy viagra

trust pharmacy canada: canada prescriptions online – canadian pharmaceutical prices

best online canadian pharcharmy legitimate online pharmacy prescription without a doctors prescription

prescription drugs without doctor: canada drug store – canadian drugs cialis

https://canadadrugs.pro/# canadian pharmacy online

online pharmacy with no prescription my canadian drug store prednisone mexican pharmacy

high street discount pharmacy: list of reputable canadian pharmacies – top rated online pharmacy

https://canadadrugs.pro/# canadian pharmacies recommended by aarp

legitimate canadian online pharmacy: trusted canadian pharmacy – canadian prescription pharmacy

cheap drugs canada canadian pharmacy in canada pharmacy drugstore online

http://canadadrugs.pro/# prescription drug prices

buy online prescription drugs: online pharmacies legitimate – overseas pharmacies

canada pharmacy online perscription drugs without prescription most trusted canadian online pharmacy

https://canadadrugs.pro/# online drugstore service canada

mexico pharmacy order online: online drug – tadalafil canadian pharmacy

cheap online pharmacy: no prescription pharmacy – online canadian pharmacy

https://canadadrugs.pro/# canadian drugs

international pharmacy: best rated canadian pharmacy – canadian pharmacy store

http://canadadrugs.pro/# top mexican pharmacies

https://canadadrugs.pro/# safe reliable canadian pharmacy

safe canadian pharmacies online: most reliable canadian pharmacy – canada pharmacy no prescription

azithromycin canadian pharmacy: canada pharmacy online – canadian pharmacy world reviews

https://canadadrugs.pro/# discount prescription drugs

canadian pharmacy usa canadian pharmacy azithromycin best online pharmacies no prescription

mail order pharmacy india Online medicine order pharmacy website india

https://edpill.cheap/# over the counter erectile dysfunction pills

online ed medications erectile dysfunction medications ed pills that work

mexican pharmaceuticals online: best online pharmacies in mexico – buying prescription drugs in mexico

https://canadianinternationalpharmacy.pro/# canada drugs online

best erectile dysfunction pills best non prescription ed pills medicine for impotence

ed pills cheap: what is the best ed pill – best male ed pills

https://certifiedpharmacymexico.pro/# medicine in mexico pharmacies

prescription drugs generic cialis without a doctor prescription prescription drugs without prior prescription

http://medicinefromindia.store/# cheapest online pharmacy india

https://medicinefromindia.store/# reputable indian online pharmacy

best online canadian pharmacy: online canadian pharmacy reviews – buying drugs from canada

http://edwithoutdoctorprescription.pro/# non prescription erection pills

mexican rx online: purple pharmacy mexico price list – mexico pharmacy

http://medicinefromindia.store/# top online pharmacy india

ed treatment drugs: erectile dysfunction drugs – best ed pills

my canadian pharmacy rx: canadian discount pharmacy – reputable canadian online pharmacies

https://certifiedpharmacymexico.pro/# mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

cialis without doctor prescription cialis without a doctor prescription canada sildenafil without a doctor’s prescription

pharmacy website india: cheapest online pharmacy india – п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india

http://edwithoutdoctorprescription.pro/# non prescription erection pills

india online pharmacy indian pharmacy online online pharmacy india

https://edpill.cheap/# best pills for ed

viagra without doctor prescription amazon: cheap cialis – п»їprescription drugs

canada discount pharmacy canadian pharmacy online northwest pharmacy canada

http://medicinefromindia.store/# indian pharmacies safe

top 10 pharmacies in india Online medicine home delivery indian pharmacy paypal

https://edwithoutdoctorprescription.pro/# best ed pills non prescription

http://medicinefromindia.store/# india pharmacy

https://edwithoutdoctorprescription.pro/# ed meds online without doctor prescription

http://medicinefromindia.store/# india online pharmacy

india pharmacy

https://certifiedpharmacymexico.pro/# mexico pharmacy

thecanadianpharmacy canadian pharmacy 24 canadian pharmacy 365

buy prescription drugs without doctor generic cialis without a doctor prescription ed meds online without doctor prescription

https://edpill.cheap/# ed pills cheap

mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa mexico drug stores pharmacies mexican rx online

buying from online mexican pharmacy buying from online mexican pharmacy mexican drugstore online

mexican pharmacy mexican pharmacy mexico drug stores pharmacies

http://mexicanph.shop/# pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

best online pharmacies in mexico

mexican mail order pharmacies mexican rx online reputable mexican pharmacies online

mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs mexican drugstore online mexico drug stores pharmacies

mexico pharmacy mexican pharmaceuticals online medicine in mexico pharmacies

purple pharmacy mexico price list mexican pharmaceuticals online buying from online mexican pharmacy

mexico drug stores pharmacies purple pharmacy mexico price list mexico drug stores pharmacies

buying prescription drugs in mexico online mexico drug stores pharmacies reputable mexican pharmacies online

purple pharmacy mexico price list mexican pharmaceuticals online mexican pharmaceuticals online

http://mexicanph.com/# mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

buying from online mexican pharmacy

п»їbest mexican online pharmacies mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

reputable mexican pharmacies online buying from online mexican pharmacy buying from online mexican pharmacy

purple pharmacy mexico price list medicine in mexico pharmacies medication from mexico pharmacy

buying prescription drugs in mexico mexico pharmacy mexican rx online

mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs mexico drug stores pharmacies reputable mexican pharmacies online

buying from online mexican pharmacy pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa best online pharmacies in mexico

best online pharmacies in mexico mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa mexican pharmaceuticals online

mexican pharmacy mexican rx online medicine in mexico pharmacies

http://mexicanph.shop/# mexico drug stores pharmacies

mexican rx online

buying prescription drugs in mexico online medication from mexico pharmacy п»їbest mexican online pharmacies

mexico drug stores pharmacies pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

medicine in mexico pharmacies п»їbest mexican online pharmacies medication from mexico pharmacy

mexico drug stores pharmacies mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa best online pharmacies in mexico

mexican drugstore online mexico pharmacy mexico drug stores pharmacies

http://mexicanph.com/# buying prescription drugs in mexico

mexican mail order pharmacies

medicine in mexico pharmacies mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa medicine in mexico pharmacies

purple pharmacy mexico price list mexican mail order pharmacies mexican pharmacy

buying prescription drugs in mexico online mexico pharmacy mexico pharmacy

mexican pharmaceuticals online reputable mexican pharmacies online medicine in mexico pharmacies

mexico pharmacy reputable mexican pharmacies online pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa mexican mail order pharmacies

mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa medication from mexico pharmacy п»їbest mexican online pharmacies

Thank you for your articles. I find them very helpful. Could you help me with something?

Thank you for providing me with these article examples. May I ask you a question?

https://mexicanph.shop/# pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

medicine in mexico pharmacies

buying prescription drugs in mexico online pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa medication from mexico pharmacy

buying prescription drugs in mexico online mexico drug stores pharmacies п»їbest mexican online pharmacies

best online pharmacies in mexico mexico drug stores pharmacies mexican mail order pharmacies

mexico drug stores pharmacies mexican pharmacy mexican pharmacy

https://mexicanph.com/# mexico drug stores pharmacies

mexican pharmaceuticals online

best online pharmacies in mexico mexico drug stores pharmacies pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

best mexican online pharmacies best mexican online pharmacies mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

How can I find out more about it?

lisinopril 80mg cheap lisinopril 40 mg order lisinopril from mexico

https://stromectol.fun/# stromectol how much it cost

54 prednisone: prednisone 10 mg online – prednisone 20

http://stromectol.fun/# ivermectin 1 topical cream

lisinopril prescription cost lisinopril price without insurance lisinopril 40 mg brand name in india

http://lisinopril.top/# zestril 2.5 mg

https://stromectol.fun/# stromectol 3 mg tablet price

how to get amoxicillin: where to buy amoxicillin – amoxicillin 250 mg capsule

where to buy amoxicillin pharmacy: amoxicillin online no prescription – buy cheap amoxicillin online

https://furosemide.guru/# lasix for sale

http://stromectol.fun/# stromectol for humans

https://lisinopril.top/# generic zestril

stromectol ivermectin 3 mg ivermectin lotion for lice п»їwhere to buy stromectol online

ivermectin 1% cream generic: ivermectin 4000 – buy ivermectin stromectol

buy lisinopril 20 mg: lisinopril for sale uk – zestoretic 10 12.5 mg

https://stromectol.fun/# how to buy stromectol

http://buyprednisone.store/# prednisone 5mg daily

https://furosemide.guru/# furosemide 40 mg

lasix furosemide Buy Furosemide lasix

prednisone cream brand name: prednisone buy without prescription – drug prices prednisone

http://amoxil.cheap/# amoxicillin in india

order amoxicillin uk where can i buy amoxocillin where to buy amoxicillin pharmacy

http://furosemide.guru/# furosemide 100 mg

http://furosemide.guru/# lasix tablet

http://stromectol.fun/# ivermectin buy online

https://amoxil.cheap/# amoxicillin 500 mg online

ivermectin price uk: ivermectin cost in usa – ivermectin 3 mg

lisinopril 20mg for sale lisinopril 5 mg tabs lisinopril 5 mg

https://furosemide.guru/# lasix 40mg

http://stromectol.fun/# ivermectin australia

stromectol tablets: ivermectin 5 – ivermectin 0.08

zestril 10 mg price zestril cost lisinopril 10 mg canada cost

http://furosemide.guru/# lasix

https://buyprednisone.store/# generic prednisone pills

http://stromectol.fun/# ivermectin 10 ml

amoxicillin from canada: where to buy amoxicillin – amoxicillin 775 mg

prednisone 20mg capsule prednisone without rx prednisone online

http://stromectol.fun/# stromectol ivermectin buy

https://lisinopril.top/# buy lisinopril 10 mg

http://stromectol.fun/# ivermectin brand name

furosemide 100mg Buy Lasix lasix furosemide 40 mg

lasix medication: Buy Furosemide – lasix furosemide

https://buyprednisone.store/# generic prednisone cost

http://stromectol.fun/# ivermectin lice oral

stromectol medication ivermectin lotion 0.5 ivermectin 1 cream

ivermectin australia: ivermectin malaria – stromectol pill price

http://amoxil.cheap/# amoxicillin 500mg capsule cost

https://amoxil.cheap/# price for amoxicillin 875 mg

ivermectin price uk: ivermectin 4 tablets price – ivermectin malaria

http://lisinopril.top/# lisinopril 100mcg

https://lisinopril.top/# zestoretic coupon

https://amoxil.cheap/# where to buy amoxicillin pharmacy

cost of ivermectin lotion ivermectin 3 mg tablet dosage buy stromectol canada

https://buyprednisone.store/# prednisone online india

lasix online: Buy Lasix – lasix uses

https://furosemide.guru/# lasix medication

http://buyprednisone.store/# purchase prednisone

stromectol tablet 3 mg: ivermectin 12 mg – ivermectin 6mg

https://lisinopril.top/# lisinopril 5 mg over the counter

https://indianph.xyz/# legitimate online pharmacies india

online pharmacy india

https://indianph.xyz/# top online pharmacy india

indian pharmacy online

reputable indian pharmacies Online medicine order online shopping pharmacy india

top 10 online pharmacy in india online pharmacy india online shopping pharmacy india

https://indianph.xyz/# buy medicines online in india

india pharmacy mail order

indian pharmacy indian pharmacy online pharmacy india

http://indianph.com/# pharmacy website india

mail order pharmacy india

cheapest online pharmacy india india online pharmacy п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india

Online medicine home delivery Online medicine order online shopping pharmacy india

https://cipro.guru/# ciprofloxacin mail online

http://cipro.guru/# buy ciprofloxacin

http://cipro.guru/# cipro

http://cytotec24.shop/# cytotec pills buy online

https://diflucan.pro/# diflucan tablets online

http://cipro.guru/# cipro generic

generic tamoxifen tamoxifen and bone density nolvadex online

how to buy doxycycline online buy doxycycline online uk doxycycline 50 mg

http://sweetiefox.online/# swetie fox

http://sweetiefox.online/# sweeti fox

http://angelawhite.pro/# Angela White video

https://evaelfie.pro/# eva elfie video

https://angelawhite.pro/# Angela White video

http://abelladanger.online/# Abella Danger

http://angelawhite.pro/# Angela White

https://abelladanger.online/# abella danger video

http://angelawhite.pro/# Angela White izle

http://sweetiefox.online/# sweeti fox

https://angelawhite.pro/# Angela White

http://abelladanger.online/# abella danger izle

http://sweetiefox.online/# Sweetie Fox izle

https://sweetiefox.online/# Sweetie Fox izle

http://evaelfie.pro/# eva elfie video

http://sweetiefox.online/# Sweetie Fox filmleri

https://angelawhite.pro/# Angela White izle

https://sweetiefox.online/# Sweetie Fox video

http://lanarhoades.fun/# lana rhoades filmleri

https://lanarhoades.fun/# lana rhoades

https://lanarhoades.fun/# lana rhoades filmleri

https://sweetiefox.online/# swetie fox

http://lanarhoades.fun/# lana rhoades video

http://angelawhite.pro/# Angela White izle

http://lanarhoades.fun/# lana rhoades modeli

fox sweetie: sweetie fox – sweetie fox full

dating direct: https://sweetiefox.pro/# sweetie fox

lana rhoades pics: lana rhoades full video – lana rhoades

lana rhoades: lana rhoades – lana rhoades videos

mia malkova only fans: mia malkova only fans – mia malkova new video

dating free online sites: http://sweetiefox.pro/# sweetie fox full video

https://evaelfie.site/# eva elfie full video

mia malkova videos: mia malkova only fans – mia malkova full video

eva elfie hot: eva elfie full video – eva elfie new video

https://miamalkova.life/# mia malkova

mia malkova only fans: mia malkova photos – mia malkova girl

mature nl free: https://miamalkova.life/# mia malkova

ph sweetie fox: fox sweetie – sweetie fox full

http://sweetiefox.pro/# sweetie fox full

mia malkova latest: mia malkova full video – mia malkova full video

eva elfie new videos: eva elfie – eva elfie new videos

https://miamalkova.life/# mia malkova photos

italian dating sites: http://lanarhoades.pro/# lana rhoades hot

ph sweetie fox: sweetie fox full – sweetie fox cosplay

Educators must adapt pedagogical approaches to harness the benefits of technology while ensuring that the human element of teaching remains central to the learning experience.

https://evaelfie.site/# eva elfie new videos

sweetie fox: sweetie fox video – sweetie fox video

sweetie fox full: ph sweetie fox – fox sweetie

mia malkova hd: mia malkova – mia malkova full video

sweetie fox full: sweetie fox new – sweetie fox full

eva elfie full videos: eva elfie – eva elfie new videos

eva elfie new video: eva elfie full video – eva elfie new video

eva elfie: eva elfie full videos – eva elfie hd

mature nl free: https://sweetiefox.pro/# sweetie fox cosplay

eva elfie hd: eva elfie new video – eva elfie photo

aviator: aviator oyunu – pin up aviator

https://aviatoroyunu.pro/# aviator oyna slot

play aviator: play aviator – aviator game online

como jogar aviator em moçambique: como jogar aviator – como jogar aviator

https://jogodeaposta.fun/# site de apostas

http://aviatormalawi.online/# aviator game

pin-up casino entrar: pin-up casino login – aviator pin up casino

site de apostas: aplicativo de aposta – melhor jogo de aposta

http://jogodeaposta.fun/# aviator jogo de aposta

aviator bet: jogar aviator online – aviator pin up

cassino pin up: pin up aviator – pin up aviator

https://aviatormocambique.site/# aviator

aviator oficial pin up: pin-up casino login – cassino pin up

aviator sportybet ghana: play aviator – aviator

aviator moçambique: como jogar aviator – como jogar aviator

pin-up casino: pin up – pin-up casino login

pin-up casino login: aviator pin up casino – pin-up casino login

aviator game online: aviator – aviator malawi

aviator betting game: aviator – aviator malawi

http://aviatorghana.pro/# aviator login

aviator bet: como jogar aviator em moçambique – aviator online

how to get zithromax online: hydroxychloroquine zinc and zithromax where can i get zithromax

http://aviatorghana.pro/# aviator game

jogo de aposta: jogos que dao dinheiro – aplicativo de aposta

zithromax z-pak price without insurance: zithromax over the counter substitute can you buy zithromax online

pin-up casino: pin up casino – pin up aviator

https://aviatormocambique.site/# aviator mocambique

aviator oyunu: aviator bahis – aviator sinyal hilesi

can you buy zithromax over the counter in canada: z-pak – zithromax zithromax for sale usa

canadapharmacyonline com: International Pharmacy delivery – canadian pharmacy in canada canadianpharm.store

http://canadianpharmlk.shop/# canadian pharmacies canadianpharm.store

mexico drug stores pharmacies: Mexico pharmacy price list – buying prescription drugs in mexico mexicanpharm.shop

pharmacy website india indian pharmacy cheapest online pharmacy india indianpharm.store

reputable indian pharmacies: Best Indian pharmacy – top 10 online pharmacy in india indianpharm.store

mail order pharmacy india: cheapest online pharmacy india – world pharmacy india indianpharm.store

pharmacy website india: Online India pharmacy – online shopping pharmacy india indianpharm.store

https://canadianpharmlk.com/# canadian pharmacy 24 canadianpharm.store

https://canadianpharmlk.shop/# legitimate canadian pharmacy online canadianpharm.store

cheapest online pharmacy india online pharmacy in india indianpharmacy com indianpharm.store

https://indianpharm24.com/# top 10 pharmacies in india indianpharm.store

https://mexicanpharm24.com/# buying prescription drugs in mexico mexicanpharm.shop

pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa: Mexico pharmacy online – mexico drug stores pharmacies mexicanpharm.shop

http://canadianpharmlk.com/# onlinecanadianpharmacy canadianpharm.store

http://mexicanpharm24.com/# buying from online mexican pharmacy mexicanpharm.shop

onlinecanadianpharmacy: International Pharmacy delivery – canadian pharmacy ltd canadianpharm.store

п»їbest mexican online pharmacies: mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa – reputable mexican pharmacies online mexicanpharm.shop

https://indianpharm24.com/# world pharmacy india indianpharm.store

https://canadianpharmlk.com/# canadian pharmacy online canadianpharm.store

canadian pharmacy mall: Best Canadian online pharmacy – legit canadian pharmacy canadianpharm.store

https://canadianpharmlk.shop/# pharmacy canadian canadianpharm.store

http://canadianpharmlk.com/# buy canadian drugs canadianpharm.store

http://canadianpharmlk.com/# onlinecanadianpharmacy canadianpharm.store

vipps approved canadian online pharmacy: Certified Canadian pharmacies – canadian pharmacy world canadianpharm.store

https://canadianpharmlk.shop/# cheapest pharmacy canada canadianpharm.store

canadian pharmacy sarasota My Canadian pharmacy canadian pharmacy checker canadianpharm.store

legit canadian pharmacy: canadian pharmacy – canadian pharmacy mall canadianpharm.store

http://indianpharm24.shop/# reputable indian online pharmacy indianpharm.store

https://indianpharm24.com/# india pharmacy indianpharm.store

http://mexicanpharm24.shop/# п»їbest mexican online pharmacies mexicanpharm.shop

This is the best weblog for anyone who wants to seek out out about this topic. You notice a lot its nearly laborious to argue with you (not that I truly would need匟aHa). You positively put a brand new spin on a topic thats been written about for years. Nice stuff, just nice!

http://mexicanpharm24.shop/# buying prescription drugs in mexico online mexicanpharm.shop

http://canadianpharmlk.com/# canadian pharmacy service canadianpharm.store

prednisone cream: prednisone buying – prednisone 50 mg coupon

prednisone over the counter australia: prednisone 5mg – prednisone for sale in canada

amoxicillin without rx amoxicillin in india generic for amoxicillin

amoxicillin 500mg capsules price: amoxicillin 500mg capsules – generic for amoxicillin

https://amoxilst.pro/# can we buy amoxcillin 500mg on ebay without prescription

where to buy clomid without insurance: long-term use of clomid in males – get generic clomid tablets

https://prednisonest.pro/# canada pharmacy prednisone

clomid without insurance: femara vs clomid – where to get generic clomid online

prednisone uk buy: prednisone dogs – prednisone 5 50mg tablet price

cost of cheap clomid without a prescription: where buy clomid – how can i get clomid prices

Hello! I’m at work browsing your blog from my new iphone! Just wanted to say I love reading your blog and look forward to all your posts! Keep up the excellent work!

can i purchase cheap clomid without rx: where to buy generic clomid now – cheap clomid now

prednisone 2.5 mg tab prednisone where can i buy can you buy prednisone over the counter in canada

can i buy cheap clomid without prescription: clomid while on trt – where to buy generic clomid tablets

https://clomidst.pro/# can you get generic clomid

how can i get generic clomid price: clomid online – can i buy clomid without prescription

http://amoxilst.pro/# buy amoxicillin online no prescription

where to get prednisone: п»їprednisone 10 mg tablet – buy prednisone without prescription

can i get clomid: clomid 50mg price – can i purchase generic clomid

prednisone 10mg for sale: prednisone prescription drug – prednisone over the counter uk

where to buy clomid without insurance: can you buy cheap clomid pill – how to buy cheap clomid

prednisone pills for sale where to buy prednisone without prescription canine prednisone 5mg no prescription

amoxicillin without prescription: amoxicillin over the counter in canada – amoxicillin discount coupon

http://amoxilst.pro/# buy amoxicillin 500mg capsules uk

can i purchase cheap clomid without insurance: clomid and twins – cheap clomid prices

online erectile dysfunction: ed meds cheap – erectile dysfunction medicine online

http://pharmnoprescription.pro/# no prescription online pharmacies

pharmacy no prescription best non prescription online pharmacy canada prescriptions by mail

online pharmacy not requiring prescription: buy prescription drugs online without – no prescription drugs online

online canadian pharmacy coupon: mexico pharmacy online – cheap pharmacy no prescription

http://edpills.guru/# best ed meds online

rx pharmacy coupons: mexican online pharmacy – prescription drugs online

http://pharmnoprescription.pro/# can i buy prescription drugs in canada

pharmacy online 365 discount code: pharmacy online – online canadian pharmacy coupon

online pharmacies without prescriptions: buying prescription medications online – buying drugs online no prescription

online prescription for ed: best ed meds online – online ed pharmacy

http://pharmnoprescription.pro/# canadian pharmacy no prescription

buying prescription drugs in india non prescription online pharmacy india mexican pharmacies no prescription

http://edpills.guru/# erectile dysfunction pills for sale

canada pharmacy not requiring prescription: mexico pharmacy online – cheapest pharmacy to get prescriptions filled

cheap erection pills: erectile dysfunction meds online – where to buy erectile dysfunction pills

https://pharmnoprescription.pro/# online pharmacy no prescriptions

ed meds cheap: cheapest ed meds – ed pills cheap

https://onlinepharmacy.cheap/# cheapest pharmacy for prescriptions without insurance

https://pharmnoprescription.pro/# online pharmacy without prescription

buying prescription drugs online canada meds no prescription buy medications without prescriptions

cheap ed treatment: erectile dysfunction medicine online – cheap ed drugs

https://edpills.guru/# erectile dysfunction drugs online

online ed pharmacy: cheap erectile dysfunction pills – buy ed pills

online canadian pharmacy no prescription: buying online prescription drugs – best online pharmacies without prescription

canadian pharmacy meds review: canada drugs online review – canadian drugs

https://canadianpharm.guru/# canadian pharmacy online store

meds online without prescription mexican pharmacy no prescription canadian drugs no prescription

canadian pharmacy no prescription: mexican pharmacy no prescription – buy pain meds online without prescription

http://mexicanpharm.online/# buying prescription drugs in mexico

reputable indian online pharmacy: buy prescription drugs from india – mail order pharmacy india

https://indianpharm.shop/# indian pharmacy online

canadian pharmacy com canadianpharmacyworld canadian mail order pharmacy

medication from mexico pharmacy: medication from mexico pharmacy – reputable mexican pharmacies online

п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india: india online pharmacy – online shopping pharmacy india

indian pharmacies safe: top 10 pharmacies in india – india pharmacy mail order

https://mexicanpharm.online/# mexican drugstore online

canada drugs without prescription: buy drugs online without a prescription – canadian pharmacy no prescription

http://indianpharm.shop/# reputable indian online pharmacy

top 10 online pharmacy in india: mail order pharmacy india – best online pharmacy india

cross border pharmacy canada: reputable canadian pharmacy – thecanadianpharmacy

https://canadianpharm.guru/# canadian pharmacy ltd

pharmacy com canada: canadian pharmacy ltd – canada rx pharmacy

online pharmacy india world pharmacy india indian pharmacy paypal

medications online without prescription: cheap drugs no prescription – buy prescription drugs without a prescription

https://pharmacynoprescription.pro/# canada pharmacy no prescription

mexico drug stores pharmacies: mexican mail order pharmacies – buying prescription drugs in mexico online

best online pharmacy that does not require a prescription in india: non prescription online pharmacy india – buy medications without prescriptions

indian pharmacy paypal: best india pharmacy – reputable indian pharmacies

https://indianpharm.shop/# Online medicine home delivery

online pharmacies no prescription: pharmacy with no prescription – prescription from canada

best mexican online pharmacies: mexican mail order pharmacies – mexico pharmacy

http://mexicanpharm.online/# mexican rx online

reputable mexican pharmacies online: medicine in mexico pharmacies – buying prescription drugs in mexico online

pharmacy website india: world pharmacy india – india pharmacy mail order

legit canadian pharmacy: trustworthy canadian pharmacy – is canadian pharmacy legit

online meds without prescription buy drugs online no prescription prescription drugs online canada

world pharmacy india: reputable indian online pharmacy – Online medicine order

https://mexicanpharm.online/# п»їbest mexican online pharmacies

mexico drug stores pharmacies: pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa – mexican pharmacy

https://mexicanpharm.online/# mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

my canadian pharmacy reviews: canadian pharmacy antibiotics – online canadian pharmacy review

http://pharmacynoprescription.pro/# buying prescription medications online

buy medicines online in india: indian pharmacies safe – best online pharmacy india

canadian pharmacy: canada ed drugs – rate canadian pharmacies

http://canadianpharm.guru/# canadian pharmacy mall

canada drug pharmacy canadian pharmacy world my canadian pharmacy reviews

online pharmacy india: legitimate online pharmacies india – Online medicine home delivery

online pharmacy india: best india pharmacy – reputable indian pharmacies

http://mexicanpharm.online/# pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

best online pharmacy india: reputable indian online pharmacy – mail order pharmacy india

http://pharmacynoprescription.pro/# online pharmacy that does not require a prescription

https://pharmacynoprescription.pro/# best online pharmacies without prescription

pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa: mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs – best online pharmacies in mexico

best online pharmacy without prescription online pharmacies without prescription prescription from canada

buying from canadian pharmacies: pharmacy wholesalers canada – canadian drugs

https://pharmacynoprescription.pro/# buy prescription online

indianpharmacy com: india pharmacy – Online medicine order

medicine in mexico pharmacies: mexican pharmacy – п»їbest mexican online pharmacies

india pharmacy: п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india – mail order pharmacy india

http://canadianpharm.guru/# precription drugs from canada

buying prescription drugs in mexico: buying prescription drugs in mexico – mexico drug stores pharmacies

https://pharmacynoprescription.pro/# meds online without prescription

indianpharmacy com: п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india – india pharmacy mail order

http://canadianpharm.guru/# canada pharmacy online legit

https://sweetbonanza.bid/# sweet bonanza yasal site

slot siteleri bonus veren: en iyi slot siteleri – slot siteleri guvenilir

http://slotsiteleri.guru/# deneme bonusu veren siteler

gates of olympus nas?l para kazanilir: pragmatic play gates of olympus – gates of olympus oyna demo

gates of olympus nas?l para kazanilir: gates of olympus oyna demo – gates of olympus oyna

http://gatesofolympus.auction/# gates of olympus demo türkçe

aviator nas?l oynan?r: aviator bahis – aviator oyunu 20 tl

https://aviatoroyna.bid/# aviator

sweet bonanza yasal site: pragmatic play sweet bonanza – sweet bonanza slot demo

https://slotsiteleri.guru/# en yeni slot siteleri

https://gatesofolympus.auction/# gates of olympus giris

aviator hilesi ucretsiz: aviator oyunu giris – aviator oyna 20 tl

aviator hilesi ucretsiz: aviator casino oyunu – aviator sinyal hilesi

http://gatesofolympus.auction/# gates of olympus oyna ücretsiz

aviator casino oyunu: aviator oyna 100 tl – ucak oyunu bahis aviator

https://sweetbonanza.bid/# sweet bonanza slot demo

https://gatesofolympus.auction/# gates of olympus

pin-up bonanza: pin-up online – pin-up casino indir

https://slotsiteleri.guru/# en çok kazandiran slot siteleri

https://aviatoroyna.bid/# aviator oyna slot

http://aviatoroyna.bid/# aviator oyunu 20 tl

gates of olympus giris: gates of olympus demo turkce oyna – gates of olympus demo

http://slotsiteleri.guru/# güvenilir slot siteleri 2024

sweet bonanza yorumlar: guncel sweet bonanza – sweet bonanza free spin demo

pin-up bonanza: pin up casino indir – pin up casino indir

http://gatesofolympus.auction/# gate of olympus hile

canada pharmacy world pills now even cheaper pharmacy canadian

mexico drug stores pharmacies: cheapest mexico drugs – pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

http://indianpharmacy.icu/# п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india

online canadian pharmacy: pills now even cheaper – canadian compounding pharmacy

online canadian pharmacy canadian pharmacy 24 canadian pharmacy antibiotics

reputable canadian online pharmacies: pills now even cheaper – canadian pharmacy king

https://indianpharmacy.icu/# Online medicine order

online canadian drugstore: Certified Canadian Pharmacy – ed drugs online from canada

buying drugs from canada canadian pharmacy 24 canadian pharmacy meds

indian pharmacy online: indian pharmacy – Online medicine home delivery

purple pharmacy mexico price list: mexico pharmacy – mexican mail order pharmacies

thecanadianpharmacy: pills now even cheaper – canadian family pharmacy

mexico drug stores pharmacies mexican drugstore online mexican drugstore online

https://mexicanpharmacy.shop/# mexico drug stores pharmacies

mexican rx online: mexico pharmacy – medication from mexico pharmacy

buying prescription drugs in mexico online reputable mexican pharmacies online pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

canadianpharmacyworld: Certified Canadian Pharmacy – canadian pharmacy tampa

legitimate canadian pharmacy: Licensed Canadian Pharmacy – canadian drug

mexican mail order pharmacies: Online Pharmacies in Mexico – mexico drug stores pharmacies

online pharmacy india: Generic Medicine India to USA – Online medicine order

https://canadianpharmacy24.store/# medication canadian pharmacy

buy prescription drugs from india: indian pharmacies safe – top 10 pharmacies in india

mexico pharmacies prescription drugs: mexico drug stores pharmacies – buying from online mexican pharmacy

amoxicillin 500mg price canada generic amoxicillin order amoxicillin online uk

https://clomidall.shop/# can i purchase clomid

cheap clomid online: how can i get cheap clomid for sale – get generic clomid no prescription

amoxicillin 500 mg brand name amoxicillin tablets in india generic amoxicillin over the counter

http://amoxilall.shop/# where can i buy amoxicillin over the counter uk

https://clomidall.shop/# buying generic clomid without a prescription

zithromax canadian pharmacy: can you buy zithromax over the counter in mexico – zithromax 500mg price

http://amoxilall.shop/# amoxicillin 500 mg

cost of clomid now where can i buy cheap clomid without insurance cost cheap clomid no prescription

https://clomidall.com/# how to get clomid without prescription

amoxicillin 30 capsules price amoxicillin over the counter in canada amoxacillian without a percription

http://amoxilall.com/# where can i buy amoxicillin over the counter uk

http://amoxilall.com/# buy amoxicillin online uk

cost cheap clomid without insurance: cost clomid without rx – can i buy generic clomid now

http://zithromaxall.com/# generic zithromax over the counter

how to purchase prednisone online: prednisone over the counter – prednisone prescription drug

http://clomidall.com/# buying cheap clomid without insurance

Cheap generic Viagra online Order Viagra 50 mg online buy Viagra over the counter

http://sildenafiliq.com/# sildenafil online

https://kamagraiq.com/# cheap kamagra

Kamagra tablets: Kamagra gel – Kamagra 100mg

Cialis without a doctor prescription cialis best price Cheap Cialis

http://tadalafiliq.shop/# Tadalafil price

Order Viagra 50 mg online: buy viagra online – Generic Viagra for sale

Kamagra 100mg: Kamagra 100mg price – cheap kamagra

https://sildenafiliq.com/# cheap viagra

https://sildenafiliq.xyz/# best price for viagra 100mg

Viagra Tablet price sildenafil iq Cheap generic Viagra

cialis generic: Cialis over the counter – cialis generic

buy Kamagra Kamagra gel Kamagra 100mg price

http://tadalafiliq.shop/# cialis for sale

Kamagra 100mg price: Kamagra Oral Jelly – Kamagra 100mg

http://tadalafiliq.shop/# Tadalafil price

http://tadalafiliq.com/# Generic Cialis without a doctor prescription

http://sildenafiliq.com/# sildenafil 50 mg price

Cheap Sildenafil 100mg sildenafil iq Cheap Sildenafil 100mg

http://tadalafiliq.shop/# Cialis 20mg price

Generic Cialis price cialis best price Cialis 20mg price in USA

https://sildenafiliq.com/# Cheapest Sildenafil online

Kamagra 100mg price: kamagra best price – Kamagra Oral Jelly

http://kamagraiq.com/# cheap kamagra

Cialis without a doctor prescription: cialis best price – Generic Tadalafil 20mg price

https://sildenafiliq.com/# Viagra tablet online

https://sildenafiliq.com/# Order Viagra 50 mg online

Kamagra tablets: Kamagra Oral Jelly Price – sildenafil oral jelly 100mg kamagra

Cheap Cialis tadalafil iq cialis for sale

https://tadalafiliq.com/# buy cialis pill

Kamagra 100mg price: Kamagra tablets – buy kamagra online usa

https://tadalafiliq.com/# Tadalafil price

Generic Cialis without a doctor prescription: cheapest cialis – cheapest cialis

https://sildenafiliq.com/# Viagra online price

Kamagra tablets: Kamagra Iq – Kamagra Oral Jelly

medicine in mexico pharmacies: Pills from Mexican Pharmacy – mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

http://canadianpharmgrx.xyz/# the canadian pharmacy

http://indianpharmgrx.com/# online shopping pharmacy india

legal canadian pharmacy online CIPA approved pharmacies pharmacy wholesalers canada

canadian pharmacy review: Cheapest drug prices Canada – canada drugs reviews

https://indianpharmgrx.com/# Online medicine home delivery

mexican mail order pharmacies: online pharmacy in Mexico – mexican pharmaceuticals online

https://indianpharmgrx.com/# top online pharmacy india

https://canadianpharmgrx.com/# the canadian pharmacy

real canadian pharmacy: canadian pharmacy – vipps approved canadian online pharmacy

https://indianpharmgrx.com/# top 10 pharmacies in india

mexican rx online mexican rx online best online pharmacies in mexico

best rated canadian pharmacy: canadian pharmacy – vipps approved canadian online pharmacy

indian pharmacy: Generic Medicine India to USA – top online pharmacy india

canadian pharmacy cheap Best Canadian online pharmacy canada pharmacy online

http://indianpharmgrx.shop/# legitimate online pharmacies india

https://mexicanpharmgrx.com/# medicine in mexico pharmacies

http://indianpharmgrx.com/# Online medicine order

top 10 pharmacies in india: indian pharmacy delivery – indian pharmacy paypal

http://mexicanpharmgrx.shop/# pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

best canadian pharmacy to order from: CIPA approved pharmacies – cross border pharmacy canada

canada pharmacy online: Pharmacies in Canada that ship to the US – recommended canadian pharmacies

http://indianpharmgrx.com/# top online pharmacy india

http://mexicanpharmgrx.shop/# buying prescription drugs in mexico online

buying prescription drugs in mexico Pills from Mexican Pharmacy mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

buy cipro online canada: ciprofloxacin generic – ciprofloxacin generic

tamoxifen for breast cancer prevention: п»їdcis tamoxifen – tamoxifen moa

doxycycline prices: doxycycline without prescription – cheap doxycycline online

http://misoprostol.top/# purchase cytotec

buy cipro online without prescription: ciprofloxacin generic – ciprofloxacin 500mg buy online

buy doxycycline online 270 tabs doxycycline hydrochloride 100mg buy doxycycline hyclate 100mg without a rx

buy cytotec: buy cytotec – Misoprostol 200 mg buy online

tamoxifen benefits: tamoxifen citrate – low dose tamoxifen

buy diflucan online cheap diflucan cream over the counter diflucan cost uk

buy cipro cheap: ciprofloxacin 500 mg tablet price – buy ciprofloxacin

buy doxycycline without prescription uk: doxycycline hydrochloride 100mg – doxycycline 500mg

Misoprostol 200 mg buy online: buy misoprostol over the counter – buy cytotec in usa

cost of diflucan over the counter: cost of diflucan over the counter – diflucan singapore pharmacy

http://ciprofloxacin.guru/# ciprofloxacin generic price

diflucan over the counter south africa diflucan 150 mg daily can i buy diflucan over the counter uk

diflucan online nz: diflucan buy – diflucan tablets price

buy cytotec pills buy cytotec online buy cytotec pills online cheap

cost of diflucan: diflucan online no prescription – diflucan tablet uk

doxycycline without a prescription: buy doxycycline online uk – buy doxycycline for dogs

how to lose weight on tamoxifen: tamoxifen rash pictures – buy nolvadex online

buy doxycycline online without prescription: buy cheap doxycycline online – vibramycin 100 mg

http://nolvadex.icu/# nolvadex gynecomastia

is nolvadex legal tamoxifen breast cancer does tamoxifen cause weight loss

purchase cipro: buy ciprofloxacin – п»їcipro generic

buy cytotec buy cytotec in usa cytotec pills buy online

where can i get diflucan: diflucan rx coupon – diflucan 100 mg

diflucan 6 tablets diflucan tablets australia 3 diflucan pills

Abortion pills online: Misoprostol 200 mg buy online – cytotec buy online usa

order diflucan online cheap: diflucan tabs – diflucan 200 mg price

http://misoprostol.top/# order cytotec online

tamoxifen and ovarian cancer: nolvadex side effects – nolvadex side effects

what is tamoxifen used for: tamoxifen joint pain – femara vs tamoxifen

where can i get zithromax over the counter where can i buy zithromax in canada zithromax prescription

40 mg prednisone pill: cortisol prednisone – prednisone 2.5 mg cost

where can i get clomid without rx: can i buy clomid no prescription – cheap clomid online

http://stromectola.top/# ivermectin 4000 mcg

buy amoxil: amoxicillin buy no prescription – amoxicillin without prescription

where to buy cheap clomid no prescription: order generic clomid without rx – can i buy clomid for sale

ivermectin 0.08 oral solution generic ivermectin ivermectin 15 mg

ivermectin cost: where to buy ivermectin cream – ivermectin 50mg/ml

amoxicillin pharmacy price: amoxicillin 750 mg price – can you buy amoxicillin over the counter canada