Benedict Evans and the team at A16Z got their hands on some detailed data on venture capital dating back to pre-2000 bubble days. There are clear indications shown in the data to deflate the current tech bubble narrative, but even further implications for both the public and private equity markets.

This Time is Different

There is a core economic theory, which I’ve used as the basis of my anti-bubble argument, called the “Boom, Bust, Buildout” theory. I wrote about it at more length here, but the argument uses history to show how many of the largest industry megatrends started with a bubble. Eventually, the bubble burst due to an influx of capital without a sustainable or mature market size to return the needed ROI on the capital. As the market matures and the large customer base required to sustain the economic growth models of businesses emerged, the bust is followed by a gradual, yet much larger, growth period which dwarfs the initial bubble in total size. This point is captured in two slides from Benedict’s charts.

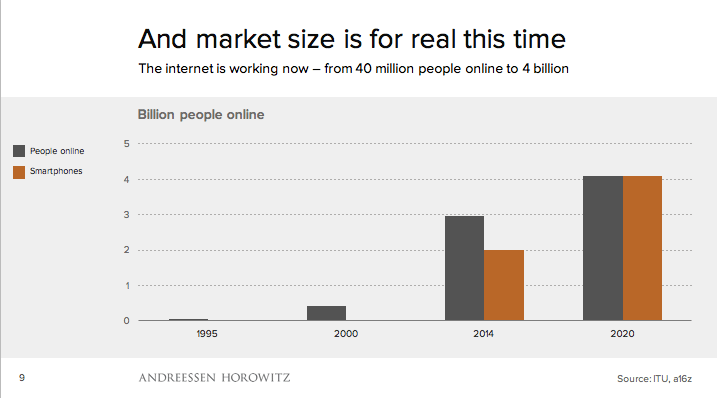

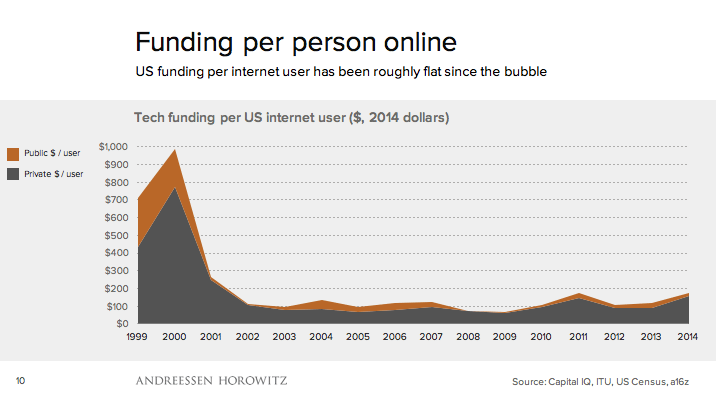

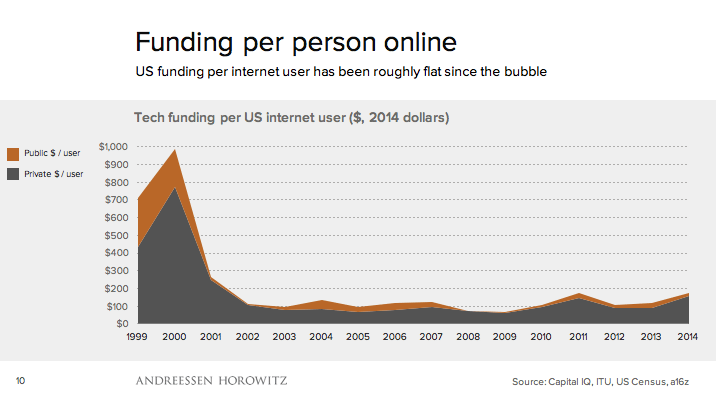

This slide shows the market sizes of actual internet users during the bubble times compared to where we will be by 2020 with nearly four billion people participating in the internet economy. This slide shows the unsustainable amount of capital per actual Internet user going back to the bubble days.

There simply weren’t enough humans participating in the internet economy to justify the amount of capital being invested per user to be sustainable. The investment per user balanced with the total market size seems much more sustainable now. The market size is four times larger than in 2000 and heading to eight times larger by 2020. Bottom line, there wasn’t really a market ready for the amount of tech investment in 2000. There is today and it’s only getting larger by billions of users, not millions.

From Public to Private

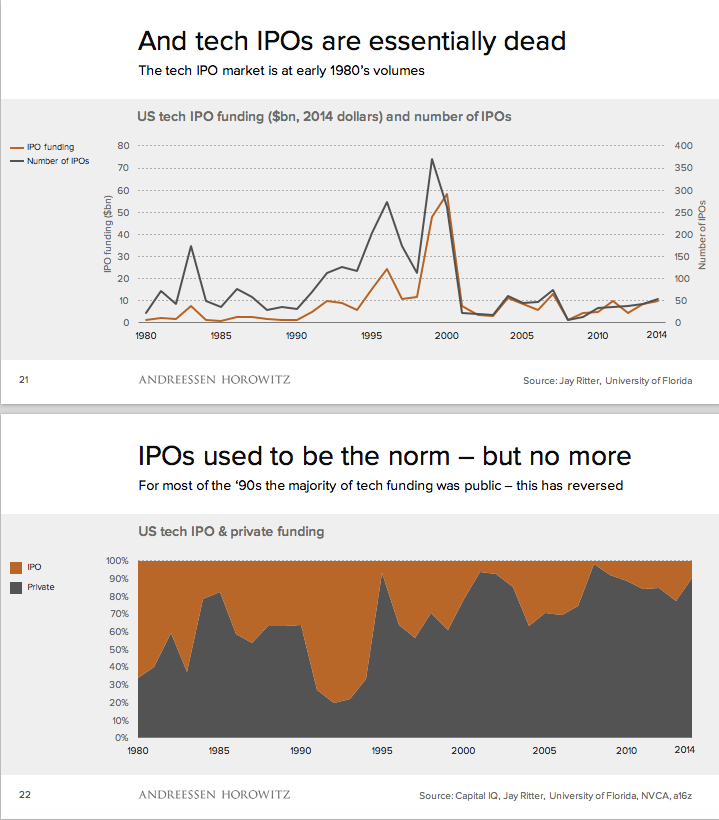

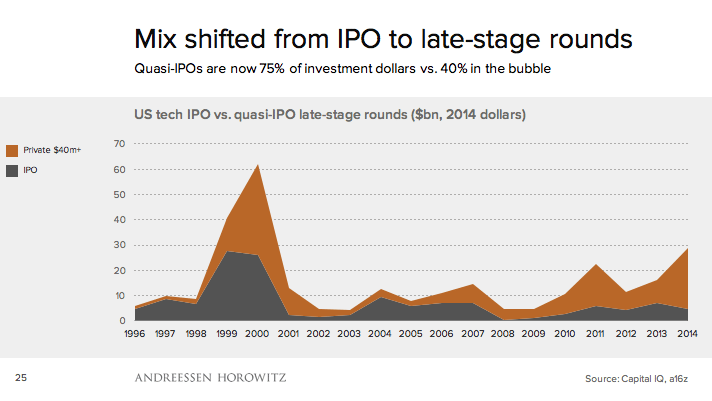

Perhaps one of the most striking shifts has been the delay in public IPOs. Part of this has to do with the ease of acquiring large amounts of money from venture capital firms. However, I also believe it is in part due to the recognition of the pressure put on public companies for short-term growth by Wall Street. It seems the short quarter-to-quarter mindset is more prevalent than the long view now more than ever with many influential public equity funds. This I believe will have an impact on the companies who do or don’t IPO in the coming years.

Assuming this trend continues, the world of private equity starts to get quite a bit more interesting. If growth is slowing and harder to come by for public companies, then I see two fascinating dynamics.

The first is how we can view venture capital as distributed R&D for larger public companies. If these private companies are not going to IPO, then investors get liquidity via acquisition. Therefore, there is a strand of thinking which must exist as VCs look to do investments from the POV of who may want to acquire the company. Similarly, big public companies may look to be aggressive with their venture arms to make strategic investments as well as strengthen their relationships with top performing VC firms.

The second is around public/private large-scale investors. If you are a large-scale investor, the public hedge funds are starting to look less interesting. There is slowing growth with many public investing hedge funds, but less risk. Many of these investors will be looking for slightly more risk but higher rewards and those investment opportunities have moved to venture capital. This risk balance is why so much money is being poured into later funding rounds in today’s venture capital economy. Once a company has proven itself by way of its business model, market position, growing customer base, or any range of metrics, the money starts pouring in. Which, as a function to itself, makes it unnecessary for a company to go public to raise money. It also fuels the shift for limited partner funds to be more aggressive with their investments in VC firms vs public hedge funds as a percentage of their investments.

Large-scale investors who used to be aggressive with the capital they manage in public markets must now shift some or more of their focus from public investing hedge funds to VC funds. Which suggests VCs are very much the new hedge funds, at least for the time being. VCs are the gateway to the private companies where nearly all the growth, risk, and reward is happening.

This has the potential to impact the VC world both positively and negatively. I’m hearing of new VC funds popping up left and right with starting funds in the $60-150m range. This is likely not sustainable as these new VC funds are being entrusted with capital to return an ROI. This is hard and takes special skill sets. While times are good to raise VC rounds, the pressure will be higher to deliver.

The trend line is clear. We are not in a bubble but are in the midst of one of the largest global technology build out phases in history. What we are observing in size, scale, and economic upside may rival the industrial revolution. How public companies via M&A, as well as private and public investors, capitalize on this growth will be a fascinating dynamic to watch.

So, a large Venture Capital firm has come to the conclusion that there’s no bubble, and that we should keep sending money their way so they can multiply it. Can you spell “conflict of interest” ?

Whatever diversion they’re throwing our way this time around, the litmus test for a bubble hasn’t changed since the tulips one: is there intrinsic value to the stuff (ie, are my shares making a reasonable return), is there expectation of a reasonable return (ie, is expected income on track to support competitive dividends and/or higher valuation).

It’s very revealing that none – NONE ! of the new discourse addresses those basics.

To rebound on your “there are more connected people” pillar… there are a lot of people breathing air, yet the air-selling business isn’t a good investment. You can find lots of people doing lots of things, it doesn’t mean all of it is a wise investment, you’ve got to find companies who actually manage to make money from those people, not just to eat up VC money.

The question also is not whether VCs think they can make more money getting out early or late, via an IPO or via going private. They’ll do whatever gets them more money. The question is: apart from VCs, who is making money ?

To be clear, I’m saying there isn’t a bubble. I’m using some of Benedict’s slides to enforce what I believe is happening. My fundamental argument is not based on Benedict’s slide deck or what most others are saying but on the basis of the economic theory of boom, bust, build out phases. This movie has played out three times before in shipping, railways, and automotive. There are very similar dynamics to the initial bubble phase, flood of unsustainable capital, lack of a market, etc., in each of those markets historically. They were then followed by a giant bell curve that dwarfed the initial bubble peak and went on for positive growth for decades. This is the phase I believe we are in right now and I still think we are in the early stages of it.

The VC angle is a new element to this theory though which makes it interesting. You are right they need to figure out liquidity. It is a dry bubble as Bill Gurley is pointing out because while values are extremely high there is no liquidity. Uber isn’t going ot get bought but also likely not going public anytime soon. Bit of a problem for VCs.

I have no idea how they navigate this angle but I do believe we will see a huge run of acquisitions at some point for many of these companies they are invested in. The public market dynamic I find fascinating also. Hedge funds are ruthless right now on their short-term thinking. I’ve only been dealing with Wall St. for 5 years or so, so I’m sure there is some historical president here but its the worst I’ve personally seen it. The pressure on public tech companies is enormous currently. Which makes it hard for a company to want to go public. Watch what happens with the FitBit IPO as well as a few others likely to happen. I think they are going to be ugly and will only serve as more deterrent for others to want to go public.

Also I encourage a read of my friend Jay’s post responding to Benedict’s deck. He doesn’t agree with all of it and its a good read.

http://digitstodollars.com/2015/06/17/what-is-a-bubble-my-response-to-ben-evans-slide-deck/

My issue is not about liquidity. It’s about revenues. There’s not one slide in the VCs’ deck about revenue. I’d ask the reverse question: what’s so wrong with revenues, which are by far the best indicator of a non-bubble, that those I’m sure very intelligent guys utterly fail to look at them ?

Obviously the VCs’ reckoning starts when they buy in, and ends when they sell out, revenues don’t matter to them as long as valuations keep rising.

Our event horizon is a bit longer though, not limited to IT, and at some point, reality rears its ugly head. We put money into companies, they’re supposed to generate revenue with it. If they’re only inflating their stock on dreams and not getting money from actual customers but only more capital to burn through, that’s the very definition of a bubble.

Not looking at revenues when discussing bubbles is surrealistic…

Revenues indicate whether a business or a sector of businesses are succeeding or not, and whether your investments are sound, but they do not tell you anything about the risk of a bubble. A collection of very large poor investments do not a bubble make.

For there to be a bubble, there needs to be more than a lot of bad investments that don’t generate returns. Those bad investments need to be used to underpin even more bad investments, and there needs to be a lot of those. This sort of behavior has to be deeply and/or broadly systemic. This is why it’s necessary to look at liquidity, asset linkages, and leverage ratios.

What made ’99 a bubble were the IPOs. The IPOs brought in a lot of public money from the general public (billions in valuation from anticipated returns on equity is very different from billions and billions of market cap that involves actual public money being sunk into assets), which is what created the liquidity, linkages, and leverage that turned a bunch of poor investments into a bubble. To say that the recent investment activity in tech is propping up a bubble is to way overstate how much money has been invested relative to the overall size of the financial industry, which pushes trillions of dollars annually, and ignores how private investing constrains the kinds of activities that would create the systemic risk of a bubble.

I understand what you’re saying. Maybe definitions vary, but I just checked about 10, they’re all a variation of wikipedia’s “A stock market bubble is a type of economic bubble taking place in stock markets when market participants drive stock prices above their value in relation to some system of stock valuation.”

No mention of scale compared to overall market, liquidity, linkage, nor leverage. Just stock price vs fundamentals. Those other things can indeed compound a bubble’s coefficient, size and the damage it causes upon bursting, thus turning a localized bubble into a major economic event. But there doesn’t need to be systemic risk for over-valuation to qualify as a bubble. Of course overvaluing one company by 20% doesn’t qualify. But I’d argue even a purely VC-circumscribed event that wiped out only say 50% of tech VCs’ assets and barely moved the needle of public stockmarkets and the economy at large would qualify as a bubble burst.

We can discuss the “system of stock valuation”, maybe IT companies have mostly fixed costs and huge as-yet untapped markets or revenue sources that make classic, more industrial-era extrapolations obsolete ?

What I’m describing is the mechanisms by which a bubble is propped up. Dig in deeper into literature on bubbles, and you’ll find that those three Ls are critical to understanding what makes a bubble a bubble. A basic definition doesn’t tell us how something happens and what we should be looking at to gauge what’s happening. The broader point I’m making though is that these things are measurable and quantifiable, and we shouldn’t overstate risk without also considering scale and proportionality. For example, a lot of the discussion about unicorns index on whether these companies are overvalued, and what happens to the overall tech sector if a bunch of unicorns die. What that perspectives misses is that what dictates whether the entire sector is being overvalued isn’t in the number of unicorns that die, but the amount of investments lost from dying unicorns vs the amount of investments gained from successful ones. So long as that ratio is positive, it’s really hard to say that the entire portfolio of investor activity is irrational and the sector as a whole is undergoing overvaluation.

“But I’d argue even a purely VC-circumscribed event that wiped out only say 50% of tech VC’s assets and barely move the needle of public stockmarkets and the economy at large would qualify as a bubble burst.”

On a technical point, you could make a case that that’s a bubble burst, but then we’d have to ask if the impacts are narrow and constrained, what was the relevance of making the point in the first place?

I think there are 3 layers to the issue, 3 reasons to make the point:

1- For investors, have most tech (or startup ?) valuations reached a level which makes investment unwise, say because there’s no way earnings will ever provide reasonable returns, the only hope is for shares to keep inflating via capital inflows.

2- for people in the IT industry (especially the ones w/o stock options or unable to cash out), are their jobs at risk because they’re living on borrowed money with no perspective of paying it back, only of borrowing more.

3- for the economy at large, could a tech bubble domino into a generalized crash.

I think the VC’s deck is a PR piece. “You’re seeing an alarming chart because you’re holding it wrong !”. Again, where are the revenues or revenue expectations to justify the valuations ?

I’m not trying to refute your skepticism about these companies valuations. I’m pointing out that if those skepticisms are confirmed that only means that those companies were bad investments, not that we’re in a bubble. Bad investments, even a whole group of them, and a bubble are not the same things.

I appreciate you sharing this blog.Really looking forward to read more. Really Great.

I do not even understand how I ended up here, but I assumed this publish used to be great

Some really excellent info, Sword lily I detected this.