Games have dominated the App Store charts for quite some time, to the extent some companies who track the app stores have started splitting games from the rest of the offerings just to see the bigger picture more accurately. This is especially the case when it comes to app store revenues, where games are often in the top grossing charts as well. Within games, however, there’s one category that’s come to dominate — the so-called “free-to-play” games, which are free to download but rely heavily on in-app purchases for monetization. The reality is these games rely heavily on a small number of paying users, with the vast majority of users paying essentially nothing most months, some users spending a higher amount on average and, within those groups, those who spend an extraordinary amount and essentially make or break a game’s success. I’ll run through each of these below, focusing on three of the major publicly traded game companies that rely on the free-to-play model: King Digital, Glu Mobile, and Zynga. At the end, I’ll come back to some conclusions about the sustainability of this model.

Many players, few payers

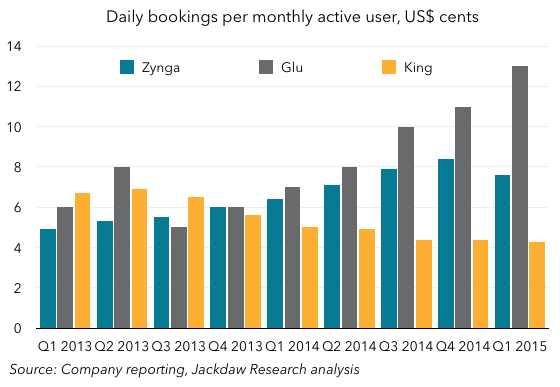

These gamemakers have several very popular game franchises, with many players. King is by far the biggest, driven by its Candy Crush franchise, with over 500 million monthly active users in total, while Zynga is considerably smaller, at around 100 million, and Glu has about half that, at just over 50 million. The average revenue per monthly user, typically measured on a daily basis, is fairly small:

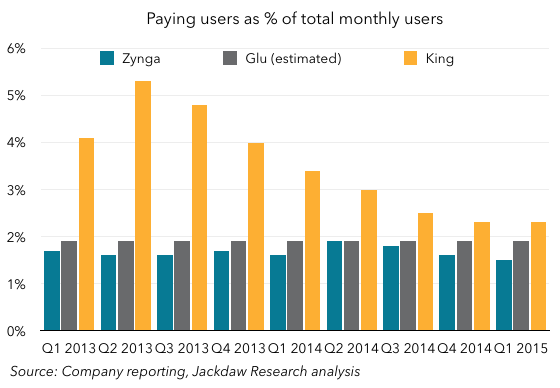

As you can see, this chart is showing cents per user per day and the range is from about four to 12 or 13 cents per user per day. Over the course of a month, that might be one to five dollars in total. But the reality is the vast majority of these users don’t pay anything during a given month:

In any particular month, only around two percent of monthly active users are also monthly unique payers. That is, 98% of users who play a game during the month don’t pay anything. It’s possible the particular users within the base who pay one month don’t during other months, but it’s likely those who do pay are the same users who cough up at least some money every month.

The few spenders spend a lot

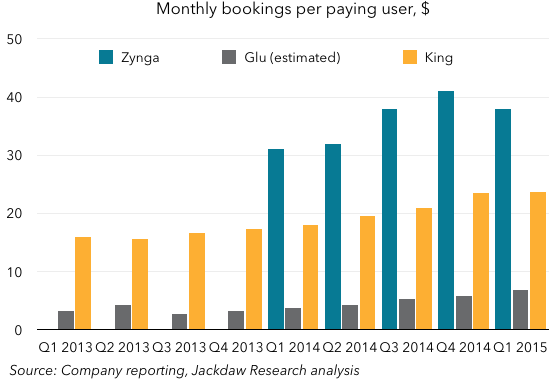

On average, these few users who do pay spend a lot of money on these games:

As you can see, the lowest number here is Glu, at under $10, but King’s paying users are spending over $20 per month, and Zynga’s users are spending over $30 per month. Given very few games on any of the app stores cost anywhere near $20-30 for a one-off purchase, these users are spending far more each month on these games than they ever would for the more expensive games outright, giving the lie to the “free-to-play” moniker for these users.

The really high spenders spend huge amounts

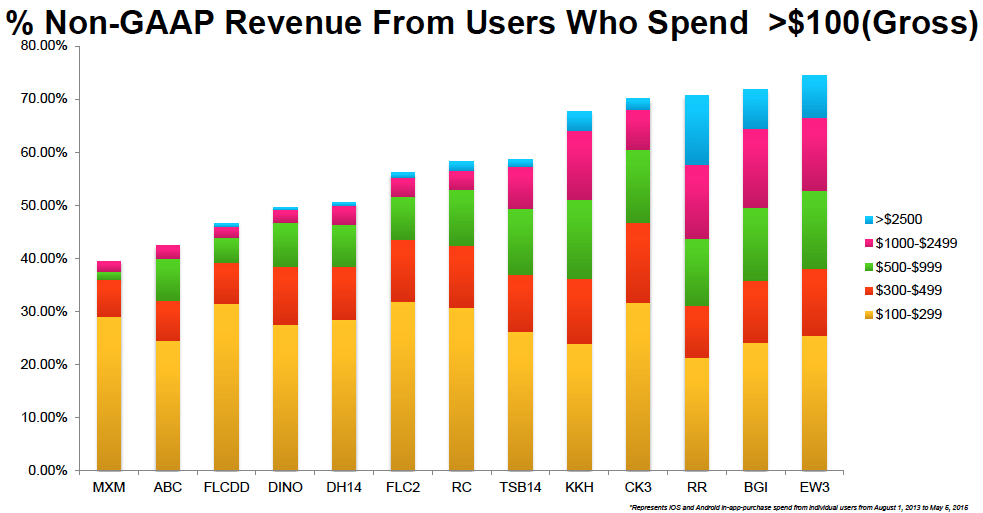

These averages, though, are still understating the skew towards those users who spend really huge amounts on games, as opposed to those who make occasional in-app purchases. You’d be forgiven for thinking even Glu’s paying users were a modest bunch, forking over $5-10 per month. But the reality is some of them are spending far in excess of this. At its recent analyst day, Glu broke out this base of paying users in more detail and I found the numbers pretty shocking. This is a chart from Glu’s investor day presentation:

What the chart shows is the percentage of revenue from users who spent certain amounts over the period from August 1, 2013 to May 5, 2015. That’s 21 months of spending, though some of these games likely haven’t been available all that time, so in some cases it’s a shorter period in reality. However, even if this represents a full 21 months of spending, only the $100 spend corresponds to the average monthly spend of around $4-5 we saw above. Every other category is spending more than that per month and the top category, spending $2500 or more over those 21 months, is spending over $100 per month on a single game. In the case of a couple of these games, that’s 5-10% of the revenue coming from these very high spending users. So, even within the spenders, there are those who spend a great deal more than the average. Revenues are therefore skewed first of all towards those who pay at all and then, within that base, to those who spend a great deal. It’s hard to escape the sense these users are addicted to the games and are willing to spend the equivalent of a higher-tier Pay TV subscription each month to continue to play.

How long can this category last?

It’s hard to know exactly how much of app store revenue comes from these free-to-play games but, based on their prevalence within the top-grossing charts (Minecraft is one of only two apps and the only game in the top 100 grossing chart on the iOS App Store that doesn’t offer in-app purchases), it’s likely these games contribute a great deal of total app revenue in the major app stores. Yet, the kind of behavior the statistics above imply suggests this isn’t an entirely healthy state of affairs, either for the game makers, which rely on fairly manipulative tactics in some cases to get people to spend money, or for the users, some of whom are spending significant amounts of money. Apple appears to recognize this, and has recently changed the “buy” button label for free apps from “Free” to “Get” in recognition that many of these apps aren’t exactly free beyond the initial download. Regulators in various countries have expressed concerns about these games, too, and I wonder how long the category can last without some regulatory intervention and potentially even serious limitations on this model. If that happens, it could have a significant impact on the overall health of the app stores and the associated revenue streams for the major platforms, especially Apple’s and Google’s, which now generate significant revenue for those companies and their developers. At this point, all the players who benefit from this model (and their investors) should be thinking very carefully about the future and the implications should it ever come under threat.

I find the subject an interesting “public education” study. Free to play games are getting better at engaging users then suckering them into paying, but at the same time, those ever-better designed pay-inducing gameplay tweaks are really starting to spoil the fun for the sane of mind, who’ll never cough up $30+ for a bathroom pastime. Will people eventually start to prefer paying $1-$10 upfront (maybe after a free trial) for a gameplay-focused app, over engaging with an app carefully crafted to turn them into credit-card wielding addicts ?

I don’t mind “idiot taxes” in general (lotteries and such, taxes on idiots), I do mind that the overwhelming dominance of F2P has made finding good up-front-payment games hard. Best value ever for me was BeloteAndr ( https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.aandrill.adless.belote&hl=en ), $5 a few years ago to get rid of ads, and my most-played game ever since.

I’m surprised no app store supports paid updates. The easiest customer is your existing customer, yet re-monetizing happy users seems to have fallen through the cracks. Subscription models probably can’t work for most games, but asking for a 50% top-up every few years for a major revision would seem logical ?

PS: a couple of things to watch out for though:

– some “offers in-app purchases” are not F2P, the in-app purchase is to get rid of apps, not to get in-game boosts. That might be unduly inflating your figures.

– not sure if that makes a difference, but Google’s app store has a 15-minutes grace period to request a refund on paid apps. IOS’s only choice is either an in-app upgrade (which goes back to my first point), or 2 separate downloads for free vs paid.

You call it “suckering”, but I’ve never spent anything in any free to play game. (The only ones I play currently are Words with Friends & Candy Crush Saga.) (I buy far more PS3 and in the past PS2 games than I play tons of, though all are $20 or under, and I will buy MANY for a couple of bucks if they go that low on the PSN.)

Also, “who’ll never cough up $30+ for a bathroom pastime”. There ARE tons of whales, however, who WILL spend tons of money on these games.

This all relates to the non-developer friendly restrictions Apple and other have implemented on app stores. In Apple’s case, they do not allow time-limited trials, paid updates or non-free pricing below $0.99 (also applies to in app purchases).

From a pure business point of view there is the challenge with intangible goods that it is often hard to charge your best users an appropriate amount. Charging for in-game goods in one way of doing that. The problem is really in the nature of the product, which relies on creating an addiction.

Ultimately, this is all very reminiscent of the gambling/betting industry, where an important part of revenue is derived from super-whales. Ethically it is all very murky and questionable. However, given the longevity of the gambling and betting industries, I suspect that this business model is not going to go away soon.

The interesting counterexample is World of Warcraft, which has maintained not only a clear leadership in MMOs but really crushed a score of free to play competitors while never going F2P itself, and limiting in-game sales to cosmetic items.

They did benefit from huge network effects, notoriety, a high barrier to entry, and being a relatively early mover.

If you consider their numbers to be trustworthy (which is hard to ascertain because neither Google not Apple provide much info), App Annie is a great free resource for data on the mobile game market. They have mentioned that game revenue is 90% of total for Google Play and 75% for App Store, and I’m sure that most of that in in-app purchases. So yes, as you mention, this unhealthy category is a huge portion of revenue for both Apple and Google.

What is more interesting however is how east asian countries are dominating this category. In the attached image taken from their report co-authored with IDC (first link below), you can see how large Asia Pacific (excluding China) is, especially for Google Play. The huge spenders in Asia Pacific are Japan, Korea and Taiwan, of which Japan is by far the biggest spender (second link).

You wonder “how long the category can last without some regulatory intervention”. To understand the possibility of this happening, what you really have to understand is the state of regulation in Japan and east asia. The way regulation is handled in western countries is not so much of an issue. What happens in east asia is much, much more important.

In Japan, as many westerners know, gambling is officially outlawed. However, the reality is very different. Japanese towns usually have big Pachinko parlours where once upon at time, one third of the population (30 million) spent 300 billion JPY (24 billion USD) per year, and not because Pachinko is a fun game, but because they could effectively gamble there.

Although there has been some government concerns over the addictiveness of some games, and the industry responded by self-regulation, you can see that the Japanese government is actually quite tolerant of gambling.

So the question is, will Japan introduce regulation to reduce the gambling and addictive aspect of mobile games? I would say that it is very unlikely. We might see some minor legislation, but nothing that would severely harm the industry.

Interestingly, Pachinko is now falling out of favour, especially among the younger generations. It is very possible that the young are playing mobile games instead.

http://blog.appannie.com/app-annie-idc-portable-gaming-report-2014-review/

http://blog.appannie.com/japan-spotlight-revenue-inflection-point/

Good article with great ideas! Thank you for this important article. Thank you very much for this wonderful information.

Good article with great ideas! Thank you for this important article. Thank you very much for this wonderful information.

Good article with great ideas! Thank you for this important article.media one live tv

Great post Thank you. look forward to the continuation.-das perfekte dinner heute live

A big thank you for your blog.Really looking forward to read more.LittleHugs Toy Straps for Baby Adjustable Toy Holder for Stroller Accessories Silicone Baby Tether Pacifier Clip No Throw Baby Travel Essential Leash for High Chair Car Seat Sippy Cups (3- Pack) – Hot Deals