Ben Thompson of Stratechery has deservedly been the talk of the tech world this week for his analysis of disruption theory, What Clayton Christensen Got Wrong. Thompson argues (and if you haven;t read his piece you should) that Christensen actually has two theories of disruption: new market disruption, in which incumbent fail to respond to basic technological change and low-end disruption, in which companies’ business models are undermined by commoditization and their inability to compete with cheaper, “good enough” offerings.

Ben Thompson of Stratechery has deservedly been the talk of the tech world this week for his analysis of disruption theory, What Clayton Christensen Got Wrong. Thompson argues (and if you haven;t read his piece you should) that Christensen actually has two theories of disruption: new market disruption, in which incumbent fail to respond to basic technological change and low-end disruption, in which companies’ business models are undermined by commoditization and their inability to compete with cheaper, “good enough” offerings.

There has been a tendency to look at the struggles of Microsoft as a case of low-cost disruption. Sales of Windows PCs are suffering because customers are settling for cheaper tablets and smartphones that are good enough for their needs. Certainly, Microsoft itself seems to look at the market that way: Its ads for the Surface focus on features the iPad lacks (“I’m sorry, I don’t have a USB port,” the tablet says in a wistful Siri voice) and Surface’s lower price.

Unfortunately for Microsoft, this misses the point. Windows has been hit by new market disruption, not its low-cost cousin. Many people–certainly myself–use an iPad not because we are willing to settle for it but because we find it meets our needs better than a laptop. I have a laptop, several of them to be precise, both Mac and Windows, but whenever I am not at my desk (where I use desktops) I will almost always go for my iPad or, if the spirit moves me, a Samsung Android tablet.

The problem from Microsoft’s point of view is that I use the tablet not because it is good enough but, for most of the jobs at hand, better. It’s always there, always on, and easily kept on my lap. Dedicated apps generally perform their chores with less fuss than their desktop equivalents.

Most studies show that tablet owners also tend to own conventional PCs. They just use them less. And because they use them less. they replacement less often, which is very bad for sales. I’m ready to replace my iMac, which I use for media production, with a newer and much faster version. Waiting 20 minutes to render six minutes of video was the last straw. But my nearly four-year-old Windows desktop is likely to go on chugging along for another year or two (on Windows 7, most likely.)

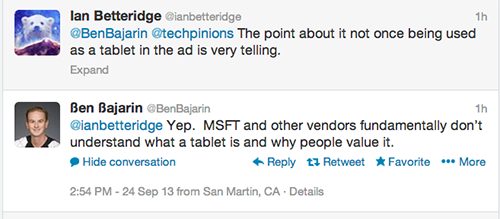

Microsoft’s response to this has been to offer a tablet that is as PC-like as possible. It is telling that the Surface (or Surface Pro) is rarely shown in ads without a keyboard. It runs a PC operating system. This Twitter dialog between Ben Bajarin and Ian Betteridge gets to the point:

Surface’s greatest point of differentiation is that in can run Microsoft Office, applications that are all but useless without a keyboard and mouse. But from Microsoft’s viewpoint, it’s better, it’s cheaper–what’s not to like?

Except that customers didn’t like the Surface, to the tune of a $900 million inventory writedown on the original version. And I don’t think they’ll be much fonder of its replacement, which offers better performance but an updated version of Windows RT, rather confusingly called Windows RT 8.1, that is only a modest improvement (at least it does limit the frequency with which the mouse-dependent Windows Desktop pops up.) It is still too PC-like and too bereft of apps to appeal.

Some companies caught by new market disruption really don’t have a chance. Kodak, for example; even if it had dominated the market for digital cameras, there just wasn’t enough money in that business to to make good the losses from film, paper, chemicals, and photofinishing services. Microsoft has the money and the opportunity to get out ahead of new markets. But like so many other incumbents, it could not loosen its grip on its lucrative legacy to seize the future. And for this it will pay dearly.