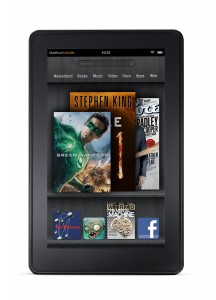

A month after its launch, Amazon’s Kindle Fire continues to be an extraordinarily polarizing product. Lots of people like it and it appears to be flying off the shelves (though it would be nice if Amazon supplied some actual numbers to back up its glowing sales reports.) But a significant element of the tech world has nothing but contempt for the 7″ ereader/tablet.

The split in opinion reflects an analytical division that has colored the debate since Amazon announced the Fire in September. Some folks see it as poor (if smaller and much cheaper) version of Apple’s iPad, while others view it as a more limited device dedicated to the consumption of Amazon content, particularly books.

The latest round of discussion was triggered by a New York Times Business Day article by David Streitfield. The piece leaned heavily on criticisms by usability guru Jakob Nielsen of the Nielsen Norman Group, who declared: “I feel the Fire is going to be a failure.” But Nielsen is no great fan of the iPad either. Though he has praised the hardware design, he has been sharply critical of both iPad apps and web sites optimized for the tablet. And his criticism of the Fire’s display of web pages in a bit odd, that pages designed for a 10″ display don’t work well on a 7″ screen. People who buy a Fire looking for a general-purposed web browser are going to be disappointed.

Streitfield’s article immediately inspired Fire defenders. In a post aptly titled “The Kindle Fire is a Kindle Killer, Not an iPad Killer–That’s Why It Works,” Search Engine Land’s Danny Sullivan wrote:

The Kindle Fire originally disappointed me. While it had the form factor I wanted, it was heavier than I wanted to hold. I’d also grown to love the e-paper format of the regular Kindles. But for the past two weeks, the Kindle Fire has grown to push aside my use of the other Kindles.

Why? For one, the screen is nice and being backlit, I don’t have to purchase a light to read at night. Consider that for the cheapest basic Kindle for $80, you’re going to spend another $60 for a case that integrates a light, if you want to read it at night. That’s $140 right there — getting pretty close to the Kindle Fire’s $200 price and gaining so much more.

…

The Kindle Fire doesn’t replace my iPad, but it sure has replaced my Kindle Keyboard. That’s the killer factor here. I think the Kindle Fire will pull more and more Kindle users into the tablet world, where for just a little more money, they get books and more — and for a lot less than buying an iPad.

At TechCrunch, John Biggs wrote:

The Kindle Fire is Amazon’s Trojan Horse. It’s made for the mass of men and women who have been looking into this whole tablet business and like what they see. But it is, first and foremost, a reading device and to fault it for not playing Angry Birds well or offering a sub-par Netflix experience is to ignore its primary goal: to inject the concept of Amazon content downloads into a consumer base that is increasingly inundated with video, audio, and ebook sources.

And Technologizer’s Harry McCracken, writing at Cnet, said:

For now, mentioning the first Kindle Fire in the same breath as the Edsel is even more of an overreaction than assuming that it was going to be an instant blockbuster. With tech products, following through on a product’s promise is at least as important as getting things right in the first place–and Amazon, unlike some of its tablet-making rivals, has a strong record when it comes to doing just that.

I’ve been using a Fire for about a month and I mostly am very happy with it. My biggest complain, shared with most users who have written about the Fire, is the relative insensitivity of the touchscreen. To the extent that is a software problem, I hope it will be addressed in an update Amazon told Streitfield to expect in a couple of weeks. Another prime candidate for an update is the rather fidgety nature of the home page that can make it hard to select one item from the ever-growing panel of favorites at the top.

Another urgent item for correction is a point made by many writers and commenters on the Amazon site. As currently configured, the fire has * no parental controls. The built-in one-click ordering lets anyone who picks it up, say your children or a total stranger, order books, videos, or music without any authentication.

The hardware is what it is and there won’t be any change until a second-generation Fire comes along, most likely in the first half of next year. But even then, don’t expect miracles. Amazon’s top priority is keeping the price low, not producing iPad-like near perfection. That means there will continue to be hardware compromises. But it also means that Amazon can continue to address a price-sensitive market interested primarily in a media consumption tablet.

The Fire will never make folks who know and love the iPad happy. The good news is that it doesn’t have to.

*–The original version said the Fire does not offer a password lock. This was incorrect and I thank Michael Gartenberg for pointing out the error.