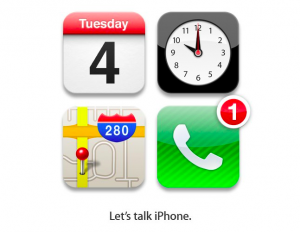

Steve Jobs posthumously set off a new round of speculation about that perennial object of desire, the Apple television, by telling biographer Walter Isaacson: “I’d like to create an integrated television set that is completely easy to use. It would be seamlessly synced with all of your devices and with iCloud. No longer would users have to fiddle with complex remotes for DVD players and cable channels. It will have the simplest user interface you could imagine. I finally cracked it.”

There’s no question that TVs and their rapidly multiplying set top boxes need a vastly simplified user interface and good reason to believe that Apple might be the company to deliver it. The problem is that if the UI were really the problem, it probably would have been solved by now. The real, and much, much harder problem is cracking the business models that control how TV content is delivered.

There’s no question that TVs and their rapidly multiplying set top boxes need a vastly simplified user interface and good reason to believe that Apple might be the company to deliver it. The problem is that if the UI were really the problem, it probably would have been solved by now. The real, and much, much harder problem is cracking the business models that control how TV content is delivered.

The failure, at least so far, of Google TV illustrates the challenge. Google set out to solve the two problems that have plagued efforts to fix television. First, you must find a way to bring together the horribly fragmented offerings of TV and movie content on the web. There’s a lot of content out there, from Hulu to Netflix to Amazon.com to iTunes to networks’ own sites. But no one site or service offers all the content a viewer might want, so a good user experience requires pulling many sources together. Second, live TV is still important for many things, especially sports, and is likely to continue to be so for a long time to come. So you need a way to integrate a live, and for practical purposes, that means a cable, feed.

Google tried to solve the first problem with the best tool it has, using search to discover web video and to try to bring it together into a common interface. Building great UIs isn’t Google’s strength, but its real problem was that content owners sabotaged the effort from the beginning. The content owners, from Hollywood studios to networks to sports leagues, live in an immensely profitable symbiosis with cable distributors. The owners and distributors have become reconciled to the idea of seeing the content on computers, tablets, and handsets, but will do everything in their power to keep it off TVs other than through their own fragmented, paid services, such as Hulu+. So they blocked Google TV’s access to these services.

The problem of integrating a live cable feed is even uglier. Google tried to solve the problem by the ugly kludge of have the Google TV box control the cable set top box, which most of the time has to be done by emulating an infrared remote control. A slightly better, but much more complex and expensive solution is to turn a third-party box into a cable STB by using CableCARDs and Tru2way software. There is every indication that the cable operators will drag their feet on allowing third parties to integrate live feeds for as long as possible.

Jobs’s cryptic remark to Isaacson gives us no clue about whether he solved these problems, but it seems unlikely. No matter how brilliant Apple is, these issues cannot be resolved unilaterally; the content owners have to be aboard. And Hollywood is, if anything, more suspicious and afraid of Apple than it is of Google.

Boosters of the Apple television idea argue that Apple went up against both the music industry and the wireless carriers and revolutionized their businesses. In the case of music, Apple went after an industry whose business model was being destroyed by massive file sharing and which, in the end, had little to lose by trying things Apple’s way.

The iPhone-carrier story is more complex. It is easy to forget that Apple initially tried to revolutionize the business by selling the original iPhone without a carrier subsidy and had to back down in the face of carrier resistance. It’s true that Apple has beaten the carriers on issues such as handset branding, but it has not changed their fundamental business model and no longer seems much interested in trying to.

The studio-sports league-cable complex promises to be a more formidable opponent than either music companies or carriers. For now, at least they have the high cards. Maybe some day Apple (or Microsoft, or Google) will look like a more attractive partner to content owners than the cable companies are. But that day seems several years away at the earliest. And until it does, TV will be a very hard nut for Apple or anyone else to crack.