September has been an unusually newsy month, and much of the news has centered on Apple’s introduction of the iPhone 5. The run-up to the announcement, the announcement itself on Sept. 12, and the first deliveries on Sept. 21 have sent the journalists, commentators, and analysts of make up the tech industry commentariat on a run of bipolar mood swings that have been a wonder to behold. Really, everybody, it’s time to take a deep breath and get a grip on ourselves.

September has been an unusually newsy month, and much of the news has centered on Apple’s introduction of the iPhone 5. The run-up to the announcement, the announcement itself on Sept. 12, and the first deliveries on Sept. 21 have sent the journalists, commentators, and analysts of make up the tech industry commentariat on a run of bipolar mood swings that have been a wonder to behold. Really, everybody, it’s time to take a deep breath and get a grip on ourselves.

The Run-up. The days before the announcement we were actually fairly calm. The rumors mostly sounded reasonable and as the 12th approached, mostly converged. By the time Tim Cook and Co. had finished their presentations in San Francisco, what we got was pretty much what the rumors had led us to expect. In fact, the last few Apple product announcements have all been well telegraphed, either because the company is managing expectations through strategic leaks or Apple’s supply chain has grown so long that and its pre-announcement production needs so great that it is impossible to maintain the secrecy of the past. Most likely, it’s some mixture of the two.

Announcement and disappointment. When Apple announced exactly what was expected, the immediate response in many quarters was crushing disappointment. It wasn’t quite clear what the iPhone lacked. The complaints seemed to mostly be that the new iPhone looked a lot like the old iPhone, even though iPhone design has been on an evolutionary course since 2007. The fact that the iPhone 5 was dramatically lighter and thinner with a much-improved display, seemed to count for little. What it really needed was a quad-core processor and near-field communications. The new Lightning connector was a disaster. The phone offered neither a hoverboard nor a jetpack.

The disappointed missed some highly significant change because it wasn’t apparent and because Apple, which generally doesn’t talk much about internals, didn’t mention it. It took chip guru Anand Lal Shimpi to find out that the A5 system-on-a-chip inside uses an Apple-designed processor in place of the modified Samsung designs used in the past. The custom chip, closely matched to Apple’s software, also a big boost in performance with what looks like a small decrease in power consumption. The result was that Apple was able to use a relatively small battery with no loss in running time. This has important implications for future designs of both the iPhone and iPad, but it went largely unremarked.

Order exhilaration Despair turned to euphoria when Apple began taking preorders and promptly announce that it had a record 2 million orders in hand and had begun pushing out promised delivery times a couple of weeks. The always optimistic and often wrong Gene Munster of Piper Jaffray forecast first-weekend sales of 120 million units with a “worst-case scenario” of 6 million. After counting buyers standing in line at Apple Stores, Munster came down the middle with a forecast of 8 million.

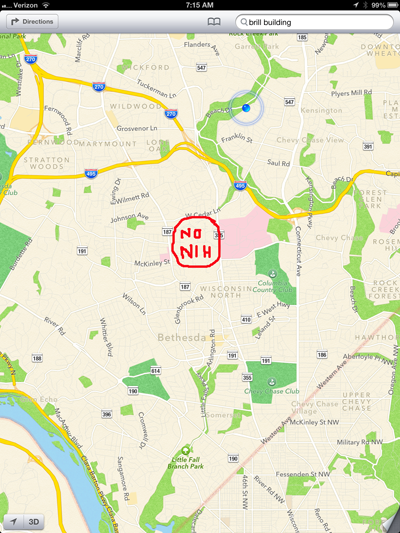

Maps, oh my. Then iOS 6.0 shipped on Sept. 19 and all hell broke loose. there were complaints that Passbook, a new service for storing tickets, boarding passes, loyalty cards, and the like seemed half-baked (In fact, I have yet to get it working at all on my 4S.) But the real furore concerned the new Apple Maps application, which replaced Google Maps.

I think the Maps imbroglio is the one serious piece of all this back and forth. Apple, in most un-Apple-like fashion, shipped a new operating system with a core function that works, at best, somewhat erratically and is markedly inferior to the app it replaced. What we don’t know is why Apple made this move at this time, specifically, whether it was Apple or Google that forced the change. Chances are we never will know, not with any real certainty. But I think Apple could risk some real reputational damage if it cannot quickly improve an mapping app that cannot get me from my suburban Washington home to Dulles airport without climbing a fence and running onto a runway.

But still, the anguish over maps, like everything else in this sequence, was overdone. Some writers said they would swear off the iPhone because Maps had lost transit instructions, somehow forgetting that Google Maps, with transit directions, worked just fine in a browser, so nothing was lost. (The bigger problem is that third-party location-based apps must use Apple’s inferior maps.)

Shipping day. Except for the usual silly stories about people standing in line at Apple Stores, shipping day was a bit of an anticlimax. By then, everything about the iPhone was known. The only real new issue was that the aluminum case, which replaced the stainless steel band and much-reviled glass back of the iPhone 4 and $S, could scratch, especially along the finely chamfered bezel that surrounds the display. It remains to be seen how serious a problem this will be as the phones get used.

The 5-million phone catastrophe. Then came the Sept. 24 news that Apple had shipped 5 million phones on the first weekend of sales. Although this was a spectacular number by any standard, it was widely seen as a disaster, coming in, as at least one headline put it “50% below expectations.”

It’s true that first-weekend iPhone sales were up only 25% over 4S sales for the comparable period, while 4S sales were roughly double sales of the iPhone 4. But it’s worth noting that a 25% growth rate is spectacular for a company of Apple’s size, and doubling could not have continued for long (see the wheat and chessboard problem.) Beyond that, we know very little about how sales are really going. Apple records a sale only when the phone is in the customer’s hands and we have no idea how many pre-orders are still in the pipeline. We have no idea the extent to which shipments were constrained by supply (Bloomberg reported that Apple is facing a shortage of displays, but that’s based on a bunch of reports by analysts who may or may not know anything.) It will take some time to get a good idea of sales; there’s every indication they are strong and the question is just how strong.

Nonetheless, Apple’s stock dropped 3% after the “disappointment.” This is still odd, since Apple is not priced like investors expect 100%, or even 25% growth. It’s price-earnings ratio is just 16, about a point higher than IBM, a company that can thrill investors with 5% growth.

Something about Apple just seems to inspire mass craziness. Much of this dates back to the days when the late Steve Jobs could seemingly pull miraculous products out of his hat and by the astonishing recent growth int he company’s sales, profits, and stock price. But it’s time for everyone to sit back, take a deep breath, and remember that Apple is a very big and very successful company. If it releases a revolutionary product every few years–I’ll argue the last was the iPad in 2010–it’s innovating better than just about anyone else on the planet. If it grows at just 15% a year, it is growing much faster than any other company its size. It operates the most successful retail stores anywhere. And it can be very successful for a very long time.

![Oops! Apple Needs a Remapping [Updated]](https://techpinions.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/apple-map.png)

![Pinch-to-Zoom and Rounded Rectangles: What the Jury Didn’t Say [Updated]](https://techpinions.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/pinch-and-stretch.png)