Last quarter, I did weekly previews during earnings season of the results coming that week. This quarter, I’m going to do just one preview piece today and then I’ll follow up in a few weeks with a review of what actually happened. I’m going to organize this by previews rather than by company but, in the process, I’ll try to touch on the major companies in the consumer technology space.

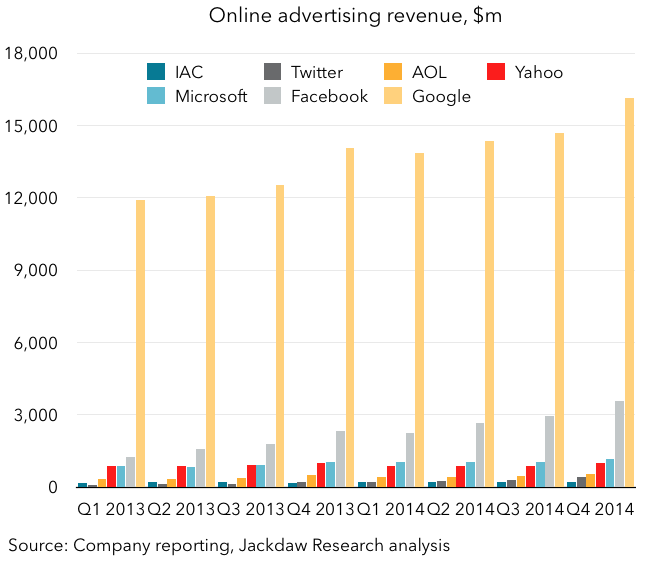

Mobile advertising

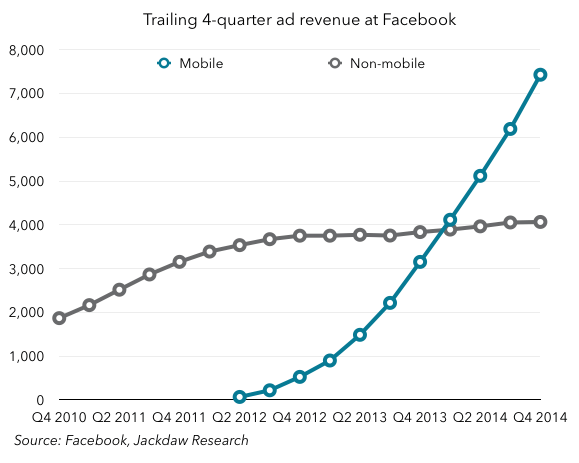

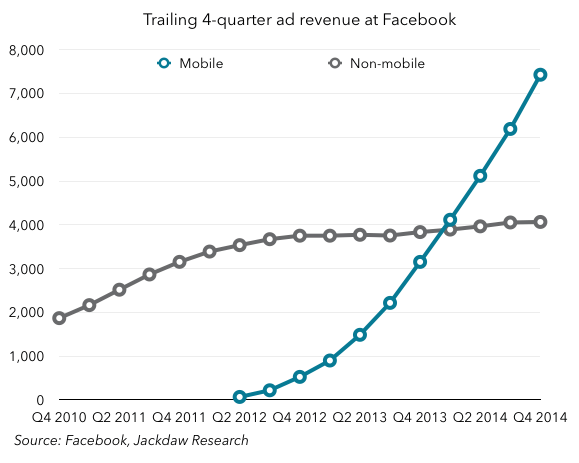

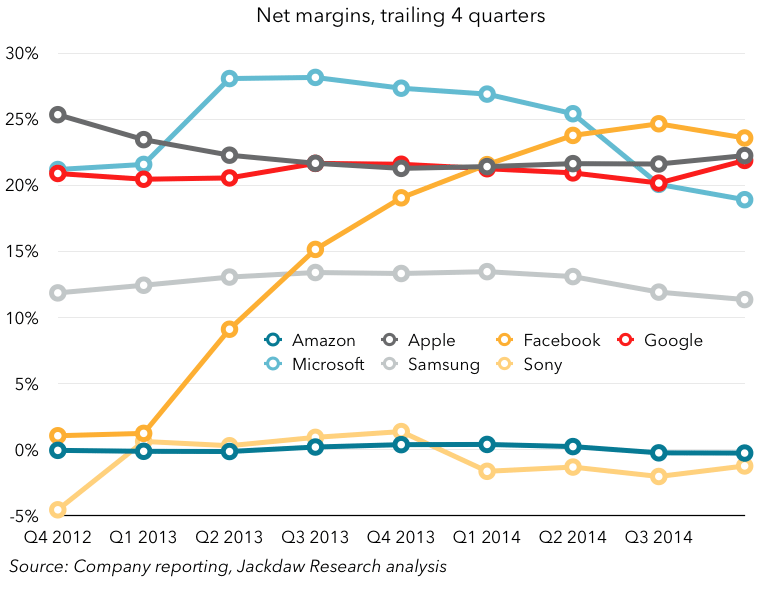

One of the biggest factors in the success or failure of some of the largest businesses in consumer tech is mobile advertising. It’s been a critical factor in Facebook’s success and growth over the last couple of years:

But it’s at least as important to several other businesses too, including Twitter, Yahoo and perhaps most critically Google. One of the big differences between these companies is the degree of transparency they provide over the transition from desktop to mobile advertising, with Facebook and Twitter being very open about it, but Yahoo providing only a little insight and only very recently, while Google’s mobile advertising revenues are a black hole. As Google’s transition to mobile takes it from a very high share and lucrative business in search to something rather different, it has to prove to investors it can capture both a high share of the market and a high share of the growth in mobile advertising and it’s not yet clear that’s the case. In addition, it’s highly dependent on search advertising revenues from iOS, which are captured through a contract that’s up for renewal shortly and could theoretically switch to another search provider. So, in all these companies’ earnings reports in the next few weeks, look out for the trends around mobile advertising, an increasingly crowded and competitive space, and the degree to which these companies are open about how these trends hurt or help their businesses.

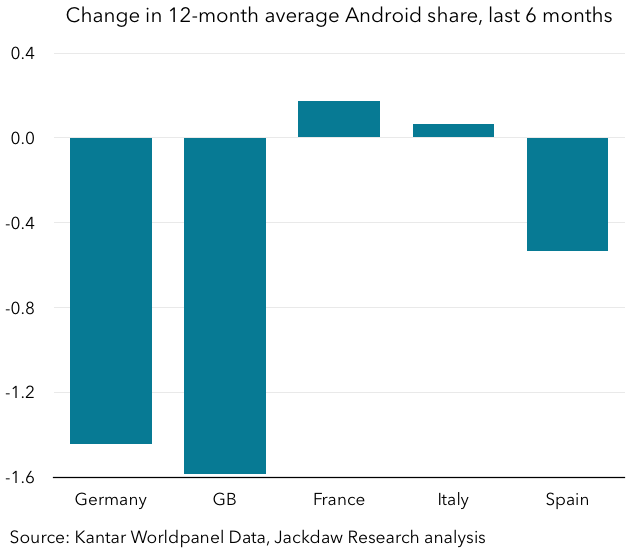

Smartphone market dynamics

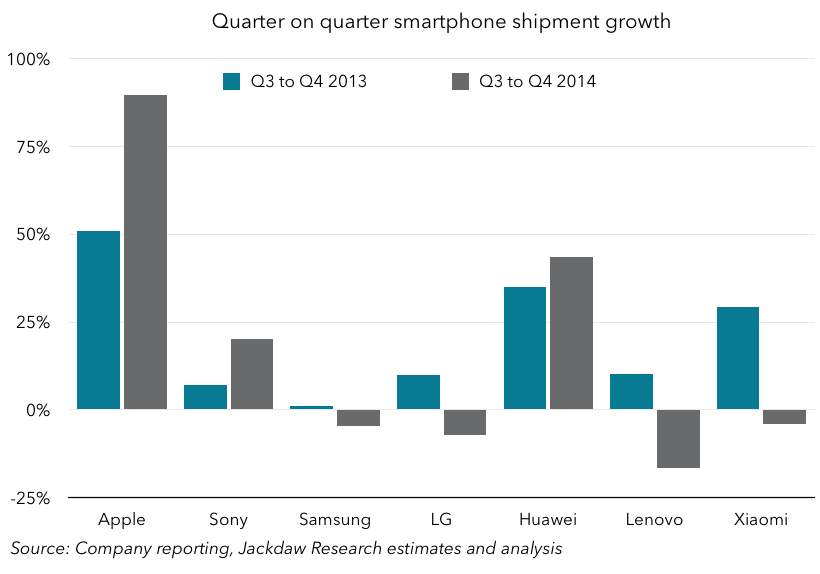

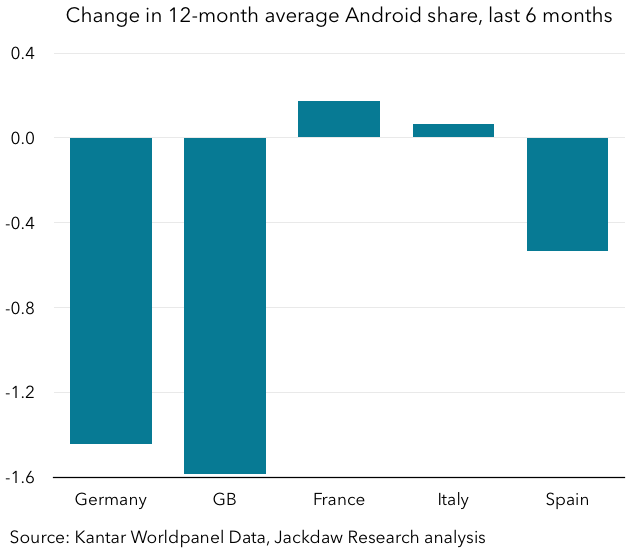

Last quarter saw the biggest quarter ever by far for the iPhone. It either tied or eclipsed Samsung’s smartphone sales depending on whose numbers you believe. But Samsung wasn’t the only vendor to suffer as a result – several other vendors saw a dip or slower growth in sales in Q4 2014 compared with Q4 2013: One of the big questions this quarter then, is whether this trend continues or whether the iPhone’s massive quarter was more of a one-off. The first quarter is normally significantly lower than Q4, but all the indications are that even Q1 will be big for the iPhone and, even though we already know Samsung’s profits recovered a little in Q1, it’s likely its shipments and smartphone revenues were down year on year. At this point, it’s posting numbers that look more at home in its 2012 results than more recent years. Xiaomi, of course, is a private company and doesn’t report directly, but the others should all be providing some visibility over their performance in the quarter and it’s well worth watching the Chinese vendors in particular. They seemed particularly hard hit in Q4 and may well be again in Q1. Sony actually had a decent Q4 in 2014, but has been struggling to maintain its momentum in smartphones, so we should watch carefully for signs things are heading south in that business. Lenovo benefited hugely from the addition of Motorola in Q4 and I’m bullish on the chances of the combined business, but it also needs to show continued momentum rather than just a couple of good quarters. Growth outside China is particularly critical.

One of the big questions this quarter then, is whether this trend continues or whether the iPhone’s massive quarter was more of a one-off. The first quarter is normally significantly lower than Q4, but all the indications are that even Q1 will be big for the iPhone and, even though we already know Samsung’s profits recovered a little in Q1, it’s likely its shipments and smartphone revenues were down year on year. At this point, it’s posting numbers that look more at home in its 2012 results than more recent years. Xiaomi, of course, is a private company and doesn’t report directly, but the others should all be providing some visibility over their performance in the quarter and it’s well worth watching the Chinese vendors in particular. They seemed particularly hard hit in Q4 and may well be again in Q1. Sony actually had a decent Q4 in 2014, but has been struggling to maintain its momentum in smartphones, so we should watch carefully for signs things are heading south in that business. Lenovo benefited hugely from the addition of Motorola in Q4 and I’m bullish on the chances of the combined business, but it also needs to show continued momentum rather than just a couple of good quarters. Growth outside China is particularly critical.

PC and tablet growth

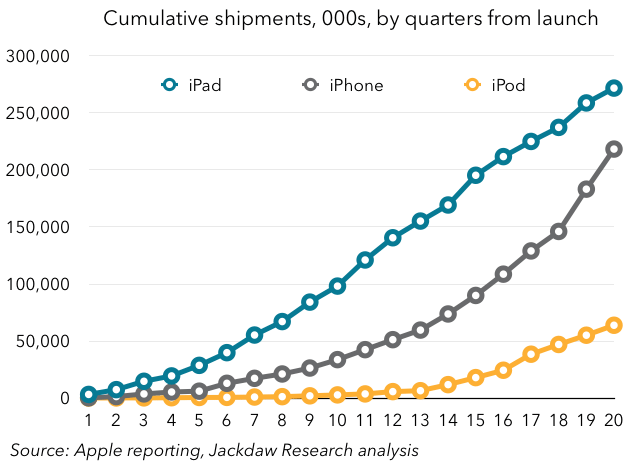

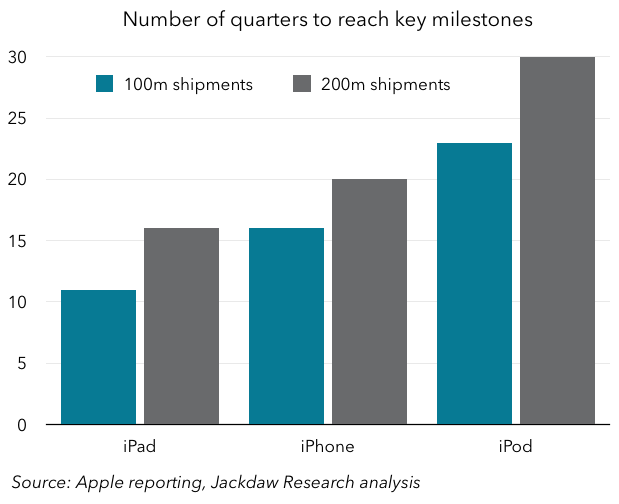

The fates of these two categories are tightly intertwined, and both have been growth-challenged lately. Ironically, Apple has bucked the trend in PCs, growing while the overall market shrinks, but the growth of the iPad has been slower than that of the overall tablet market, partly because it competes at the premium end and what growth is occurring is largely at the cheaper end of the market. I wrote about the iPad’s fifth birthday recently, so I won’t go into that at length, but I still believe 2015 is the year we’ll see whether the slowdown in sales is just a factor of long replacement cycles or whether there’s something else at work. I continue to believe the former plays a big part, but I also think both more portable laptops and larger smartphones are eating into the iPad’s role as an in-between device. In PCs, early indications are it was another rough quarter for the market but that shouldn’t surprise anyone who understands the state of the PC market. When “good” quarters are characterized by smaller declines than forecast, it’s time to accept the PC category is in permanent decline, even if the decline might be a bit slower than some people believed. Slower replacement cycles, the growth in alternative computing form factors from smartphones to tablets to wearables and the growing share of the Mac means the Windows PC market in particular is tough. This quarter, watch for anyone whose results go against the trend, which will include Apple but quite likely Lenovo too.

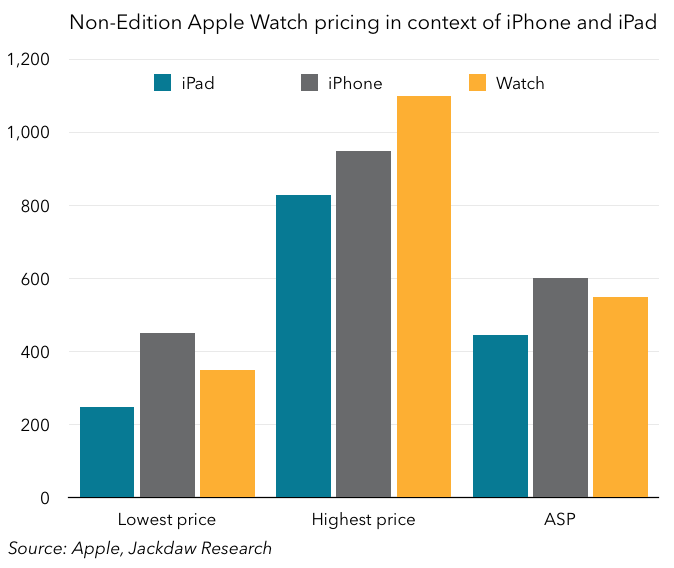

Wearables – early hints of the Watch, and the rest

The Apple Watch went on sale after the quarter ended but it’s obviously going to be a major theme on Apple’s earnings call. We already know Apple isn’t going to report Watches as a separate segment for the time being, and to me that’s a signal we may well not get much detail at all on sales in the near term. With the reports in the last week or so of very small inventories available at launch and long ship times, it seems even more likely Apple will hold off on reporting numbers in much detail, since the numbers are far more reflective of supply constraints than demand. That won’t stop financial analysts from trying multiple angles on the call to get more information out of Apple on sales numbers, average selling prices, and so on, but I’d expect Apple to give very little away. Beyond Apple, the wearables category is a bit like the iPad category: lots of competing devices, many of them being given away with smartphone purchases, but few of them truly competitive with the Watch. As I said in my piece a week ago, that doesn’t mean they won’t sell and they’ll actually benefit from the release of the Watch. For now though, sales of other wearables will be a fraction of the Watch, and won’t likely make a blip on other companies’ earnings calls.

Video moves and trends

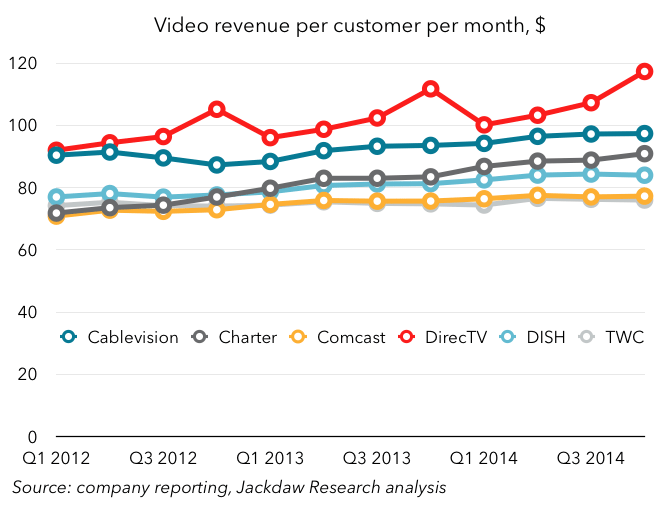

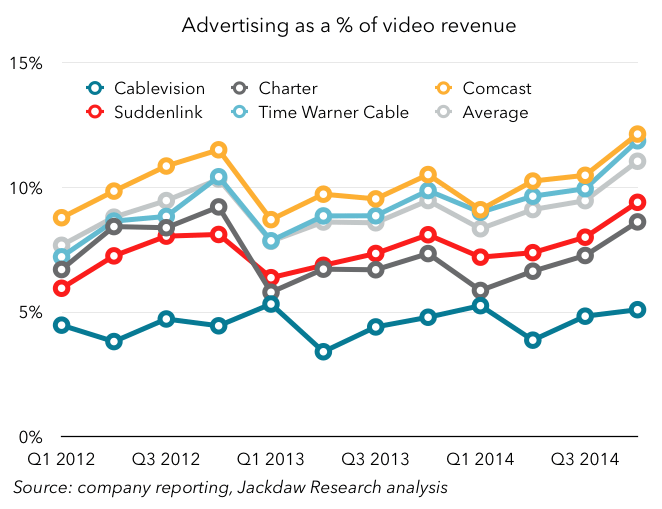

Video is by far the biggest content category, and there’s a huge amount of revenue tied up in companies which exclusively provide video content or services (broadcasters, cable networks, subscription video-on-demand services and so on), but also many other companies which are either already major beneficiaries from the video market or looking to get in on the action. The major Pay TV companies represent the old guard here and have seen slowing growth but not yet declines in overall subscriptions, but there’s a raft of new players emerging and some of the traditional companies are also experimenting with new models. Sony, DISH, and Verizon are among the companies tinkering with alternatives to the classic pay TV service today, though Verizon’s proposed a la carte bundles seem to have run into a contract issue with the content providers. Apple is also, of course, reported to be working on something here and there will undoubtedly be questions about this on the earnings call though I don’t expect Apple to answer them. More fundamentally, many of the old media companies are suffering from the decline in traditional live viewing and their inability to track and monetize non-live viewing effectively and Apple’s entry could accelerate this as it solves some of these problems. Expect many of the cable networks and broadcasters to continue to report declining advertising revenues during their earnings calls, with little evidence they have a way to turn the trend around.

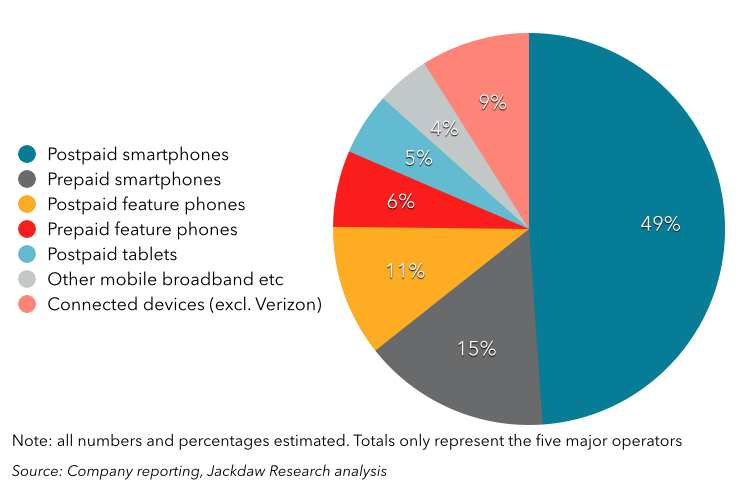

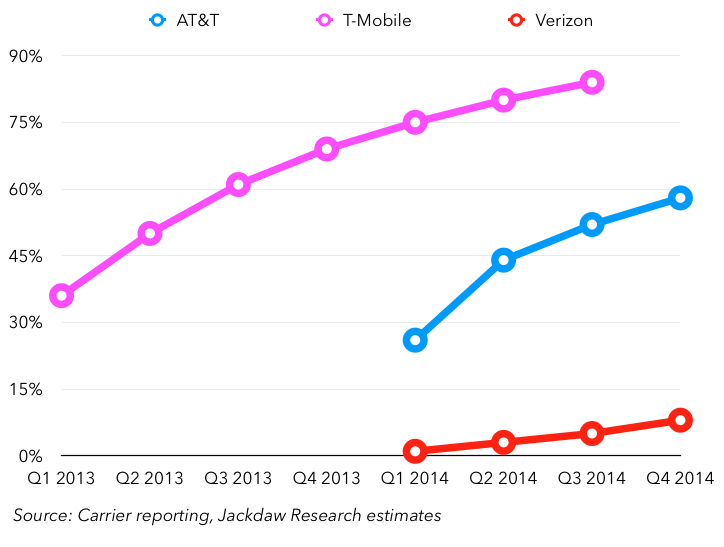

Wireless carrier performance

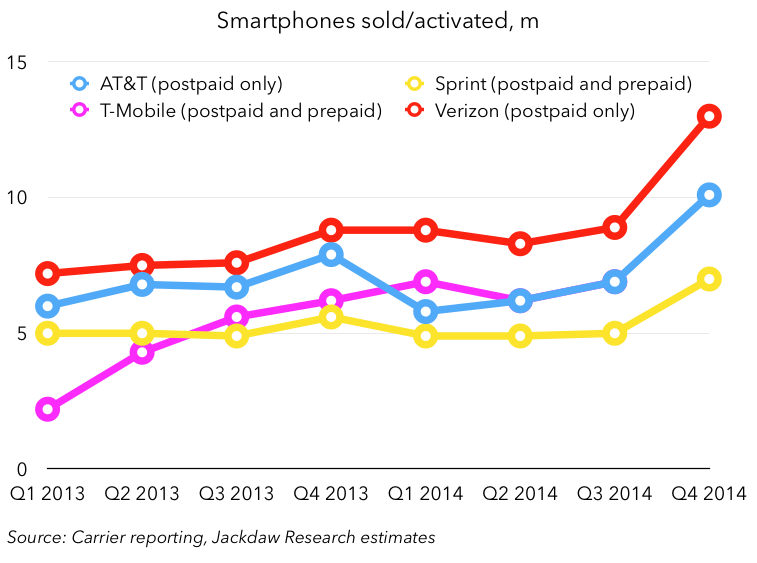

I’m going to conclude with a set of companies I track closely, and that’s the US wireless carriers, principally the four largest (AT&T, Sprint, T-Mobile, and Verizon). These companies are engaged in the bitterest, most competitive period of recent history, as growth in phone subscribers dries up and the two smaller carriers in particular fight aggressively for customers. T-Mobile has been threatening to pass Sprint for third place in the market but Sprint has been working to improve its subscriber growth so this may not happen this quarter, though it’s largely symbolic anyway – T-Mobile is much bigger in prepaid while Sprint is far larger in postpaid services. Verizon and AT&T had been largely immune to the onslaught for some time but, in the latter half of 2014, had to begin to respond more aggressively and it’s worth watching for their churn levels and subscriber growth in Q1. Another thing worth watching for is the growth in phone subscribers versus other areas, which I’ve talked about at length previously. Phone subscribers haven’t been growing much, and much of the actual growth has been in tablets (largely Android tablets given away for free with smartphones), and “connected devices” (mostly machine to machine and other embedded connectivity such as connected cars). As competition for phone subscribers becomes increasingly a zero-sum game, carriers’ ability to tap into these other areas becomes important, and so far AT&T and Verizon are running away with the connected devices and tablet opportunities respectively. A big question this quarter is whether Sprint and T-Mobile can start making a better showing in these two areas.

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/3510782/microsoftvsgooglevsapple.0.jpg)

The four carriers who have reported so far had 30.1 million smartphone sales between them and T-Mobile may well have had another 8-10 million too. The move to installment billing certainly doesn’t seem to be hurting device sales so far.

The four carriers who have reported so far had 30.1 million smartphone sales between them and T-Mobile may well have had another 8-10 million too. The move to installment billing certainly doesn’t seem to be hurting device sales so far.

For most of these large Android vendors, growth rates from Q3 to Q4 this year were significantly worse than Q3 to Q4 rates last year. Lenovo (excluding Motorola) and Xiaomi were particularly badly hit, with most of their shipments in China, but Samsung and LG also saw quarter on quarter declines. Among vendors, only Huawei and Sony managed to weather the iPhone’s impact. At Samsung of course, there are longer term challenges at play but, for most of these vendors, the iPhone accounts for a substantial portion of the impact.

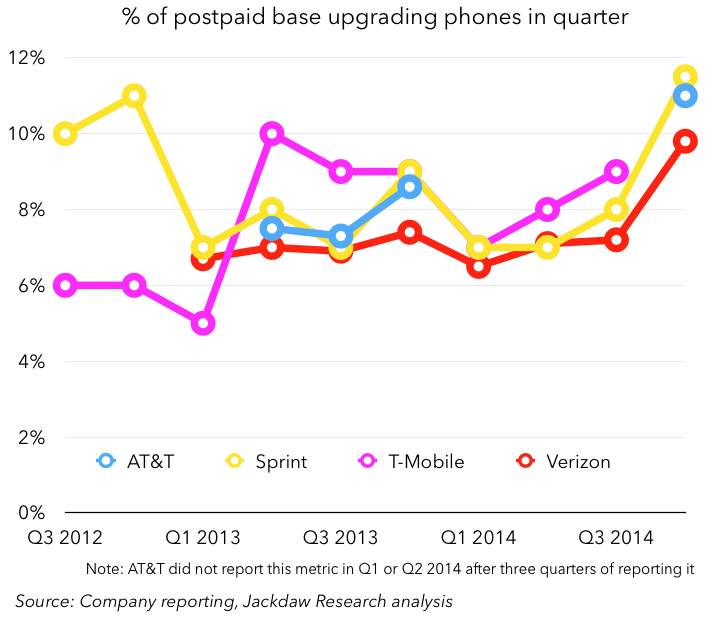

For most of these large Android vendors, growth rates from Q3 to Q4 this year were significantly worse than Q3 to Q4 rates last year. Lenovo (excluding Motorola) and Xiaomi were particularly badly hit, with most of their shipments in China, but Samsung and LG also saw quarter on quarter declines. Among vendors, only Huawei and Sony managed to weather the iPhone’s impact. At Samsung of course, there are longer term challenges at play but, for most of these vendors, the iPhone accounts for a substantial portion of the impact. All three of the big carriers have reported a higher percentage of upgrades than in any quarter in the past three years and I would expect T-Mobile to join them. Several factors play into this. The iPhone 6 and 6 Plus obviously drove a big iPhone upgrade cycle, but another major factor was the move to installment-based billing. There’s been quite some debate about whether this new model will stimulate or slow smartphone sales, but this quarter it was a huge factor for all carriers and they all sold tons of smartphones as a result. In Q4 alone, the four big carriers likely sold almost 40 million smartphones between them. Despite this upgrade behavior, however, the vast majority of the subscribers these carriers added in the quarter were not new smartphone lines, but tablets and “connected devices” (machine to machine subscriptions, e-readers and the like).

All three of the big carriers have reported a higher percentage of upgrades than in any quarter in the past three years and I would expect T-Mobile to join them. Several factors play into this. The iPhone 6 and 6 Plus obviously drove a big iPhone upgrade cycle, but another major factor was the move to installment-based billing. There’s been quite some debate about whether this new model will stimulate or slow smartphone sales, but this quarter it was a huge factor for all carriers and they all sold tons of smartphones as a result. In Q4 alone, the four big carriers likely sold almost 40 million smartphones between them. Despite this upgrade behavior, however, the vast majority of the subscribers these carriers added in the quarter were not new smartphone lines, but tablets and “connected devices” (machine to machine subscriptions, e-readers and the like). Meanwhile, Twitter reported just 230 million mobile MAUs, a number that has barely moved since last quarter (its overall MAU number didn’t grow by much either). These numbers just reinforce the difference in scale and breadth of appeal for Twitter and Facebook in their core products. But this doesn’t tell the whole story. Facebook’s entire product is private and based on being logged in to an account. But Twitter’s product is inherently public. So much of the exposure most people get to Twitter is not through the core service itself but through embedded tweets, hashtags on TV, and so on. Twitter is at a crossroads in terms of its user growth: it clearly believes it can get MAU growth going again, but even if it does, it’s simply not going to be on a trajectory to reach Facebook (or Google) scale. But Twitter’s management seems to believe it can capture another kind of audience that isn’t logged in (and may not even have an account). It already attracts a pretty significant audience this way but it makes almost no effort to monetize it yet. That’s the next challenge for Twitter.

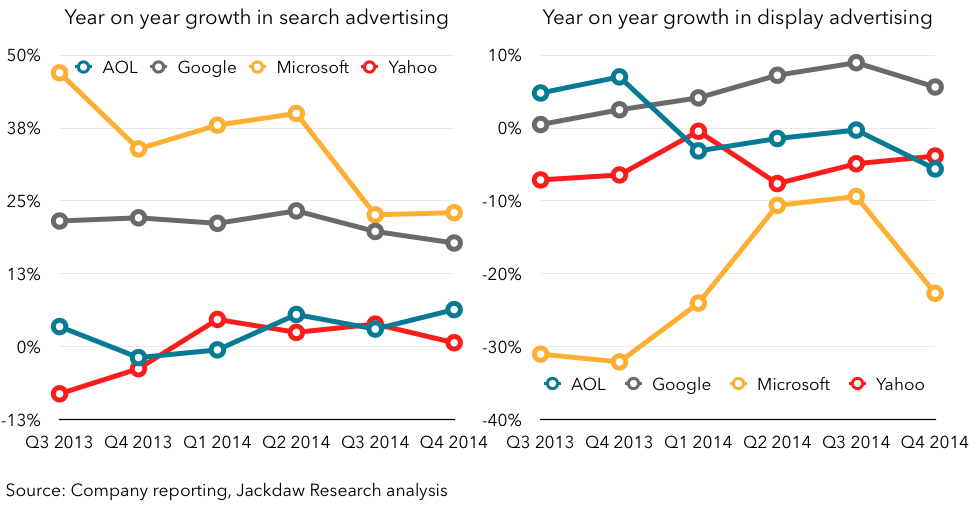

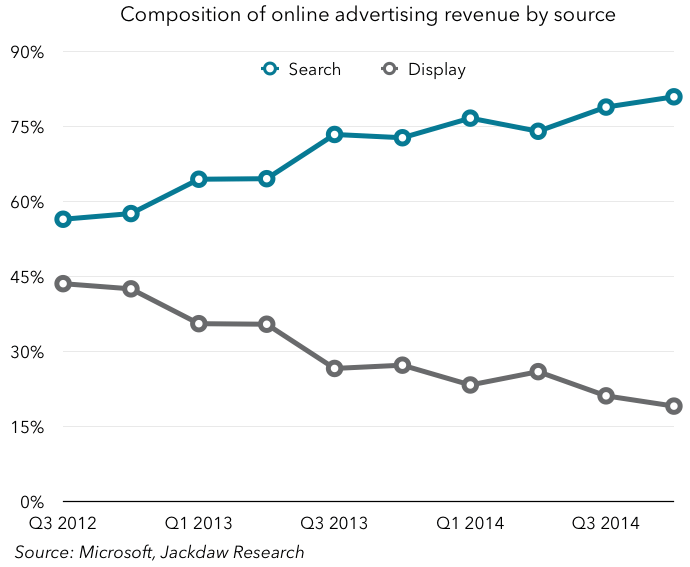

Meanwhile, Twitter reported just 230 million mobile MAUs, a number that has barely moved since last quarter (its overall MAU number didn’t grow by much either). These numbers just reinforce the difference in scale and breadth of appeal for Twitter and Facebook in their core products. But this doesn’t tell the whole story. Facebook’s entire product is private and based on being logged in to an account. But Twitter’s product is inherently public. So much of the exposure most people get to Twitter is not through the core service itself but through embedded tweets, hashtags on TV, and so on. Twitter is at a crossroads in terms of its user growth: it clearly believes it can get MAU growth going again, but even if it does, it’s simply not going to be on a trajectory to reach Facebook (or Google) scale. But Twitter’s management seems to believe it can capture another kind of audience that isn’t logged in (and may not even have an account). It already attracts a pretty significant audience this way but it makes almost no effort to monetize it yet. That’s the next challenge for Twitter. This illustrates the divergence nicely, because this is happening across major companies that play in the advertising space, whether Google, Yahoo, IAC, AOL or whoever. Display ad prices are falling, clicks aren’t growing as fast, and the business is generally performing much worse than other forms of online advertising. Meanwhile, search continues to be a very lucrative business for those who offer it, notably Google (though even there, there are signs of challenges). But the other major growth areas are native advertising, whether at Facebook or Twitter or news sites such as Buzzfeed, and video advertising, which is obviously already a huge business at YouTube, but is also increasingly important at Facebook, which now reports 3 billion views a day. Of course, Twitter and Snapchat both recently announced video products both for users and advertisers, and Instagram has tweaked its video product too. Video will be increasingly important for these companies in generating ad revenue, especially as non-native display advertising continues to suffer.

This illustrates the divergence nicely, because this is happening across major companies that play in the advertising space, whether Google, Yahoo, IAC, AOL or whoever. Display ad prices are falling, clicks aren’t growing as fast, and the business is generally performing much worse than other forms of online advertising. Meanwhile, search continues to be a very lucrative business for those who offer it, notably Google (though even there, there are signs of challenges). But the other major growth areas are native advertising, whether at Facebook or Twitter or news sites such as Buzzfeed, and video advertising, which is obviously already a huge business at YouTube, but is also increasingly important at Facebook, which now reports 3 billion views a day. Of course, Twitter and Snapchat both recently announced video products both for users and advertisers, and Instagram has tweaked its video product too. Video will be increasingly important for these companies in generating ad revenue, especially as non-native display advertising continues to suffer.

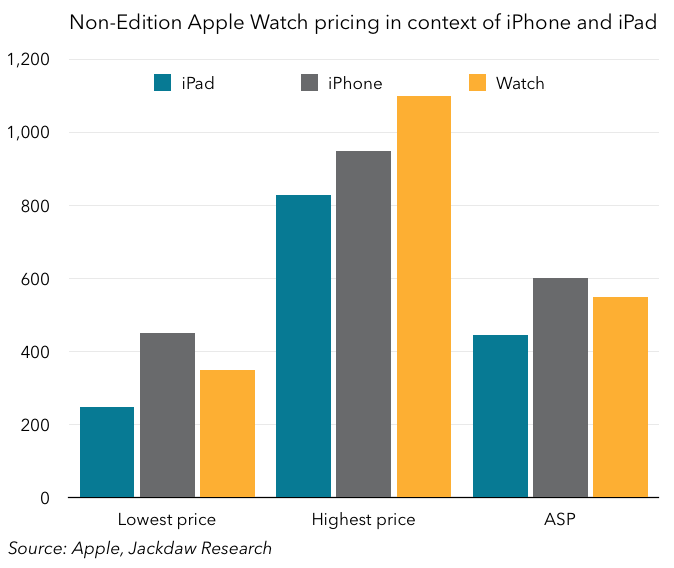

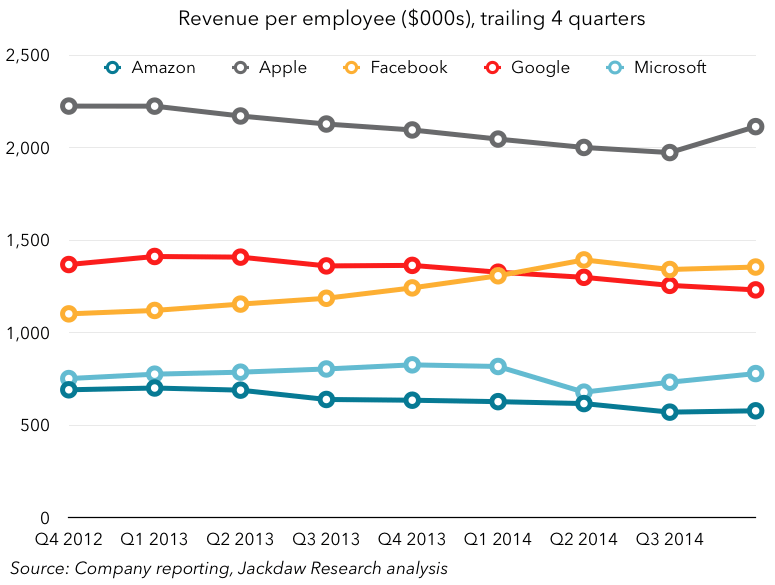

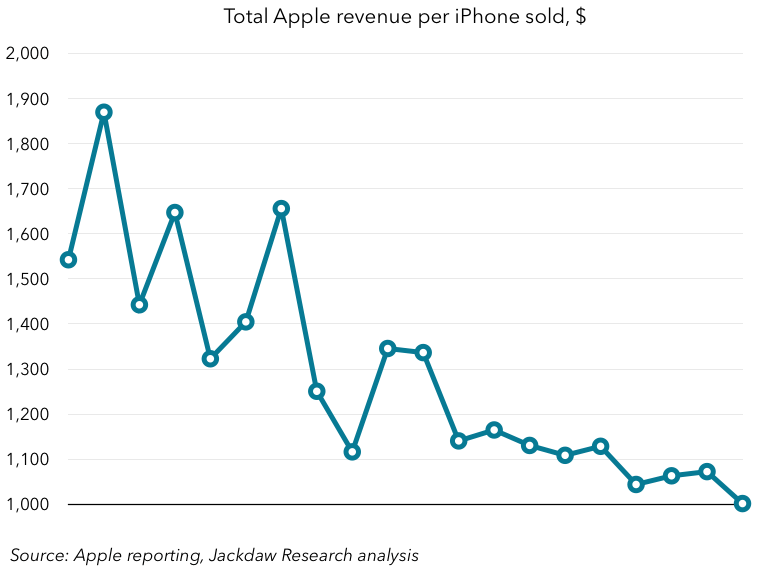

What I want to look at today is the degree to which the iPhone has become central to the Apple ecosystem and the degree to which Apple can essentially be seen as the iPhone company. To some extent, we can also begin thinking about “the iPhone economy” as existing beyond the confines of Apple itself. What the chart shows is Apple is starting to stabilize at around $1,000-$1,100 per quarter per iPhone sold in total revenue. Now, iPhones themselves account for somewhere between $600 and $700 of that $1000, but the rest is made up of other devices and services and that’s where I want to focus our analysis.

What I want to look at today is the degree to which the iPhone has become central to the Apple ecosystem and the degree to which Apple can essentially be seen as the iPhone company. To some extent, we can also begin thinking about “the iPhone economy” as existing beyond the confines of Apple itself. What the chart shows is Apple is starting to stabilize at around $1,000-$1,100 per quarter per iPhone sold in total revenue. Now, iPhones themselves account for somewhere between $600 and $700 of that $1000, but the rest is made up of other devices and services and that’s where I want to focus our analysis.